This year marks the 200th anniversary of London’s National Gallery. From humble beginnings it has grown into a cultural icon of the United Kingdom, housing some 2,400 works and now attracting several million visitors a year.

The concept of a National Gallery was born after the death of John Julius Angerstein, a banker and marine insurance broker who founded the insurance company Lloyd’s of London and amassed a splendid art collection from across Europe. When he died in 1823, his heirs decided to sell his collection. In April 1824 the House of Commons agreed to pay £57,000 (about $75,000) for his 38 paintings, which would form the heart of Britain’s new national art collection.

On May 10 of that year, the public—the great, the good and the grittier types from the streets of King George IV’s London—was invited into Angerstein’s house at 100 Pall Mall, an elegant domestic setting, to review the works firsthand, but the press reaction was underwhelming, and crowds did not stream in. However, the astounding quality of the works acquired for the nation—a purchasing tradition that the gallery continues to this day—was clear. Parliament agreed to construct a building for the National Gallery at Trafalgar Square, the site of the current venue at the very center of London. Seven years later the gallery opened, in 1838.

To kick off its 200th anniversary celebrations, titled NG200, the museum hosted an impressive light show on the facade of its building and toured many of its invaluable works, deemed “national treasures,” around the United Kingdom. It is now preparing a redisplay of the collection, including all the touring treasures, opening in May 2025.

In the spirit of celebration, we offer our own tour: a look at 20 highlights of the National Gallery collection.

-

The Wilton Diptych, 1395–99

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Commissioned by King Richard II of England, this small, foldable diptych was made for the king’s personal use in prayer—and we know it was well used, because the exterior panel is very worn. It’s odd that he was praying to a depiction of himself being praised by the baby Christ. But then again, he wasn’t the most liked of kings, so perhaps he needed to. Here, in this portable bit of heaven, we see the lavish use of extensive gold and ultramarine, both extremely expensive materials because of their rarity and purity. Painted in the then-new “international style” with its neat arrangement of characters, slender bodies and hands, and regimented angels’ wings, the interior of the panel shows King Richard II kneeling in prayer while St. John the Baptist and two patron saints of the royal family commend him to the Holy Virgin and Christ Child, who are situated in a flowery paradise surrounded by angels.

This work will be on view March 8–June 22, 2025

-

Uccello, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1470

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Paolo di Dono, known by his nickname Uccello—“bird” in Italian—was an early-Renaissance artist striving to master the art of visual perspective in paint. Many cite The Battle of San Romano (1438–40), also in Room D, as the finest work by Uccello at the National Gallery, but Saint George and the Dragon shows much more flair. The San Romano scene demonstrates how Uccello was working out perspective, with the orthogonal lines of spears and other weapons clearly marking out a grid the artist could populate with horses and a marvelously foreshortened knight lying face down, but the overall work is not as refined, nor does it feel as finished, as Saint George and the Dragon, hanging just a few feet away. Though smaller, this canvas shows a more sophisticated understanding of space. Uccello here managed to use less pronounced visual elements to create his perspectival grid, achieving a landscape with real depth.

On view in Room D

-

Sandro Botticelli, Venus and Mars, c. 1485

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. The lovely thing about Botticelli, an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance, is that unlike the innumerable artists painting biblical scenes in the 15th century, he enjoyed portraying polytheistic deities—as in this painting of Venus and her lover Mars, both Roman gods. Here we see a delightfully down-to-earth narrative, in which a plump, toddler-like satyr blows a conch loudly into the sleeping Mars’s ear while three others muck about with his armor. Far from chiding them, Venus seems lost in thought. The work, recently on loan as part of the National Treasures program to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, does not go back on display until the grand rehang in May. If you visit earlier, there’s a wonderful, smaller Botticelli in Room D, Mystic Nativity (1500), which combines contemporaneous politics with Nativity and paganistic elements.

This work will be on view starting in May 2025 in Room D

-

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist, c. 1506–08

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. This astounding charcoal and chalk drawing by High Renaissance artist, inventor, and theorist Leonardo da Vinci, is one of the most magical of his works. Also called The Burlington House Cartoon, it had been looked after by the Royal Academy of Arts since the 18th century but was set to leave the United Kingdom when the RA put it up for auction in 1962. Luckily, the National Gallery launched a public appeal on March 30 of that year for £800,000 (about $1 million)—still thought of as a colossal sum for any artwork, let alone a drawing made on eight sheets of paper glued together. On July 31, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan announced that a special government grant of £350,000 would rescue Leonardo’s work for the nation. And thank goodness it’s on view in a public collection. The almost palpable warmth between the two women depicted is countered by the looseness of the materials that Leonardo used; it’s as if the figures could disappear at any moment. Ironically, before the May rehang, you can see the work at the Royal Academy of Arts, in Burlington House, down the road (November 9, 2024–February 16, 2025).

This work will be on view starting in May 2025

-

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. The Arnolfini Portrait is one of early Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck’s masterworks. Every item of dress in it presents sartorial elegance without flashiness; the couple’s clothes are expensive and fashionable but there’s no real bling. It’s a highly structured setting, yet the informality of some elements—oranges scattered, clogs strewn aside, slippers in the background—suggests the subjects may have been friends of the artist, and indeed we can see Van Eyck and his assistant reflected in the convex mirror on the far wall. For many years it was thought to portray a wedding, but it is now thought to be simply a double portrait. Oh, and the woman isn’t pregnant, she’s just holding her multilayered skirts off the floor.

On view in Room 28

-

Raphael, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1507

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Italian High Renaissance painter Raphael’s work has been intrinsic to the National Gallery since Portrait of Pope Julius II (1511), on display in Room 12, entered the original Angerstein Collection in 1824. However, in Room 26 you can view his Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a more signature work that captures the saint in religious ecstasy, lips parted and hand on heart. In a triangular composition typical of the high Renaissance, Catherine is shown cloaked in flowing, naturalistic robes with her head twisted away from her body. Catherine of Alexandria was a 4th-century princess who was converted to Christianity by a desert hermit and, in a vision, underwent a mystic marriage with Christ. When she would not renounce her faith, the Emperor Maxentius devised an instrument of torture consisting of four spiked wheels to which she was bound, but a thunderbolt destroyed it before it could harm her. Catherine was later beheaded. This captivating work encapsulates the femininity and fragility of its subject.

This work will be on view starting November 27, 2024, in Room 26

-

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. At first glance, the object floating in the foreground of this painting is a mystery. But viewed from a very oblique angle, it’s a skull. It’s one of the more striking features of The Ambassadors, a painting by northern Renaissance master and King’s Painter to Henry VIII, Hans Holbein the Younger. The pictured Tudor noblemen were Jean de Dinteville, left, who was on his second diplomatic mission to England on behalf of France’s King Francis I, and his pious friend Georges de Selve, right. Dinteville was one of Francis’s most trusted courtiers and had attended the wedding of King Henry VIII to his second wife, Anne Boleyn, in 1533, the same year this work was painted. The portrait alludes to the political unrest of the time through the misalignment of scientific instruments on the upper shelf. On the lower shelf a book is open on a page beginning with the word dividirt, meaning “let division be made,” a reference to the religious schism in Europe caused by England’s split from Rome. The lute’s broken string symbolizes discord, while the music book is open on a hymn to the Holy Spirit, perhaps invoking ecclesiastical reunification. Dinteville had described himself as “melancholy, weary and wearisome,” and perhaps his mood inspired the painting’s memento mori in the form of an anamorphic skull.

On view in Room 12

-

Titian, Diana and Actaeon, 1556–59

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Painted in the 1550s for Prince Phillip, later Phillip II of Spain, Diana and Actaeon is one of six large mythological paintings that the Italian Renaissance master Titian based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This work, jointly bought for the United Kingdom by the National Gallery and the National Galleries of Scotland in 2009, shows why Titian is so important: he unlocked a new level of realism and movement in his art. See how the young hunter Actaeon brushes away a curtain hiding the secret bathing spot of Diana, goddess of the hunt, and her virginal nymphs. Though some of the nymphs look surprised, some don’t. Perhaps that’s because Titian may have at times used courtesans as models for his character studies. Diana, trying to cover herself with a veil, looks outraged, and it won’t be long before she will turn Actaeon into a stag and set her hounds on him.

On view in Room 29

-

Anthony van Dyck, Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, c. 1638–39

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. In 1940, during the Second World War, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered that the National Gallery’s collection be buried “in caves and cellars” to escape the predicted carpet bombing from Hitler’s Luftwaffe. And so they were, including this enormous work by King Charles I’s court painter, Anthony van Dyck, depicting the king on horseback, resplendent and ready for battle. Charles I was a great patron of the arts, holding many important works in his collection, some of which also now reside at the National Gallery. But back to the top-secret wartime evacuation of the gallery’s 2,000 works: Experts scoured the country for a hiding place until they found Manod Quarry in Gwynedd, Wales. With a cavernous space at its heart covered with hundreds of feet of slate and granite, the mine was virtually impregnable to bombing. But the Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, at 12 by 9.5 feet, was too tall for its carrier truck to navigate around a tight S-bend. The road had to be dug deeper to lower the truck by a few inches, and to this day the curb in that section is noticeably higher.

On view in Room 21

-

Johannes Vermeer, A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal, c. 1670–72

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. “The Sphinx of Delft” is the nickname that the art historian Théophile Bürger gave the Dutch painter Vermeer when he discovered the artist in the 19th century, alluding to the enigmatic presence of people in his works and how elusive he was as an historical figure. This painting and what is thought to make up its partner piece, A Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (also from c. 1670–72, and also in Room 19), display Vermeer’s typically still interiors with characterfully aloof people within them. These two paintings seem to make a pair describing virtue and loyalty in the standing young woman and perhaps promiscuity and flirtation in her seated counterpart, an interpretation given weight by the painting in the background, which depicts a prostitute flirting with clients.

On view in Room 19

-

Canaletto, A Regatta on the Grand Canal, c. 1740

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. By the end of the 17th century, it was popular for young noblemen to go on a “grand tour” of Europe with the aim of furthering their artistic education. And every so-called “grand tourist” worth his salt would go to Venice and pick up a painting by the Venetian School artist Canaletto. Canaletto pounced on this as a lucrative business opportunity and (with the help of his studio workers) started knocking out picturesque scenes such as this one for touring aristocrats to snap up. Depicting the February regatta celebrating the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin, the painting captures a traditional Venetian event, making it a perfect souvenir. It is one of the most detailed versions the artist made of the same scene, but he produced many others. Once whisked off home, such a work could be used as proof of one’s attendance at the affair, even if one had missed it entirely because of a dreadful hangover.

On view in Room 33

-

William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête, c. 1743

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Part of the National Gallery’s founding Angerstein collection of 38 paintings, the six canvases in English artist and satirist William Hogarth’s “Marriage A-la-Mode” series offer a morality tale of the disastrous consequences of wedding for money rather than love. Focusing on a couple whose marriage has been arranged by their fathers for titles and cash, Hogarth’s series, rife with symbolism throughout, is viscerally disturbing. The husband contracts syphilis from his extramarital exploits, and the wife takes a lover. The story comes to a climax as the wife’s paramour stabs to death the weakened, syphilitic husband. In the final scene, the wife takes a fatal dose of laudanum when he is hanged for murder. In this, the second of the six paintings, a clock shows that it is past noon. The wife is taking a late breakfast as her husband slumps in a nearby chair. It appears they’ve both had a wild night, but—judging from the damp spot on the wife’s skirt and the woman’s nightcap stuffed in her husband’s pocket—not with each other.

On view in Room 34

-

Joseph Wright of Derby, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Eighteenth-century English portraitist Joseph Wright of Derby is perhaps better known for having given scenes of scientific and industrial advancement an importance traditionally reserved for historical and religious subjects. This painting about the pursuit of scientific knowledge in the Age of Enlightenment doubles as a commentary on the fragility of life. A traveling lecturer conducts an experiment in front of an private audience of aristocratic viewers, showing how a bird will suffer (and perhaps die, unless the lecturer has mercy on it) in a vacuum. Dramatically illuminated by a candle, the onlookers are variously distressed, distracted, and absorbed as the bird struggles for air. It has been noted that while this experiment was conducted at the time on a range of animals, birds, and insects, the bird depicted here, a rare white cockatiel, would likely not have been used in in such a way (unless it is, in this fictional drama, a family pet). Although the implied value of this particular animal may constitute a nod to the preciousness of all animal’s lives, Wright leaves that determination up to the viewer.

On view in Room 34

-

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, c. 1750

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Also in Room 34 is this image of a husband and wife by the quintessentially British painter Thomas Gainsborough. Born and raised in Suffolk, Gainsborough worked mainly in London, where he became a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts. Most people think of Gainsborough as a portraitist—one of whose great rivals was Joshua Reynolds, on display in the same room—but what he really enjoyed was landscape painting. To create his bucolic English countrysides, Gainsborough would often use broccoli for trees and lumps of coal for rocks to study placement and composition. The subjects of Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, an Essex squire and his wife, posed for Gainsborough under an oak tree at the point where their house’s lawn met their farmland. The unpainted patch in Mrs Andrew’s lap is a mystery; some think it could have been intended for a pheasant shot by her husband, while others think it was reserved for the addition of a baby later on.

On view in Room 34

-

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. After being on loan to the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, this painting is back at the National Gallery, reappearing in a display dedicated to its creation. Depicting an idyllic rural landscape just minutes away from where the artist grew up in Suffolk, it belies an altogether more foreboding reality. Constable composed this pastoral vision when the truth of what was happening in the English countryside was quite different: steam trains had begun coursing through the landscape and poverty-stricken farmworkers were quickly being replaced by mechanized equipment. The Hay Wain portrays an England already of the past, an idealized view of what once was.

On view in the Sunley Room through February 2, 2025

-

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway, 1844

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. In stark contrast to Constable, his contemporary J. M. W. Turner was all about crystallizing modernity. This painting celebrates the achievement of the British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his Great Western Railway, but it also pits human technology against nature, here in the form of a hare. To the left of the central image of a train barreling toward us is a small boat on a river far below, and to the right is a man driving a horse-drawn plough, both much slower than the train. Even so, steam trains at this time, while the height of technology, would likely only reach a speed of about 33 mph, so it is in fact the hare running ahead of the train that is the fastest. Unfortunately, it’s hard to see the hare in the painting nowadays because Turner swiftly added the animal the day before the painting was exhibited, and the paint has become virtually transparent over time. (Luckily, it is captured in an engraving by Robert Brandard that is held by the Tate.) On display in the same room is Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (1839), depicting the old oak warship being hauled to the scrapyard by a newfangled steam-powered tug. In this work, the sun—embodied by the multi-colored sky—is literally setting on the age of sail.

On view in Room 34

-

Claude Monet, Bathers at La Grenouillère, 1869

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. If you’re mad keen on French Impressionist Claude Monet’s paintings of water lilies, head to Room 41, but please also seek out his more exciting Bathers in Room 44. This masterful composition, an iconic work that brought painting forward by leaps and bounds, shows members of modern society relaxing in the then popular Parisian suburb of La Grenouillère. It was only in 1874 that the Impressionism movement was founded, so this can be seen as an influential forerunner. Monet’s asymmetrical composition, his use of complementary colors—influenced by Michel Eugene Chevreul’s 1839 color wheel—and his depiction of a scene “en plein air” all contributed to the artistic movement to come. Don’t miss Monet’s other works in this room, plus Edouard Manet’s Execution of Maximilian (c. 1867–68).

On view in Room 44

-

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Breaking down color and light into separate dots of pigment, French painter Georges Seurat depicted a different suburb of Paris on the River Seine in his mammoth painting Bathers at Asnières. The inventor of the post-Impressionist style of pointillism, Seurat was essentially experimenting with how color mixed in the viewer’s eye. Look closely and you’ll see that every square inch of the painting is made up of hundreds of dabs of different hues, which all coalesce into as scene of impending modernity (note the factories belching smoke in the distance). Look around the same room for another leap forward in Paul Cezanne’s works Hillside in Provence (1890–92) and Curtain, Jug and Dish of Fruit (1893–94).

On view in Room 43

-

Henri Rousseau, Surprised!, 1891

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. An all-time favorite of gallery visitors, this painting by naïve—or primitive—French artist Henri Rousseau captures an imaginary scene of a tiger in a lightning storm. Rousseau never left France (the flora and fauna in his works were based on travel books and trips to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris) and was what we might call a “Sunday painter” until he retired from his job at age 49 to make art full time. His talent was recognized during his lifetime though, when the artist Félix Vallotton wrote, “His tiger . . . ought not to be missed: it is the alpha and omega of painting . . . . As a matter of fact, not everyone laughs, and some who do are quickly brought up short. There is always something beautiful about seeing a faith, any faith, so pitilessly expressed.” Recently the focus of a month-long kids’ program at the National Gallery, the work continues to inspire, and the question remains, is the tiger—who here seems as startled as a house cat by the lightning—or its intended and offscreen prey who is actually the surprised party?

On view in Room 41

-

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888

Image Credit: Copyright © The National Gallery, London. Dutch post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh painted four versions of Sunflowers in just one week, in anticipation of a long-awaited visit from a supposed friend, the painter Paul Gauguin. “I am painting with the gusto of a Marseillaise eating bouillabaisse,” Vincent wrote to his brother Theo. The yellow sunflowers symbolize happiness and stand in for the sun-drenched fields of Provence, where the artist was living, but the joy this painting was meant to bring was, for the artist, quashed by his subsequent quarrels with Gauguin. At least we can still appreciate how Van Gogh described them in a letter to the painter Émile Bernard in 1888: “Raw and broken chrome yellow will blaze forth on various backgrounds, blues between pale véronèse [emerald green] and royal blue, framed with thin strips painted in mine orange [red lead pigment].”

On view in Room 6

The Wilton Diptych, 1395–99

Commissioned by King Richard II of England, this small, foldable diptych was made for the king’s personal use in prayer—and we know it was well used, because the exterior panel is very worn. It’s odd that he was praying to a depiction of himself being praised by the baby Christ. But then again, he wasn’t the most liked of kings, so perhaps he needed to. Here, in this portable bit of heaven, we see the lavish use of extensive gold and ultramarine, both extremely expensive materials because of their rarity and purity. Painted in the then-new “international style” with its neat arrangement of characters, slender bodies and hands, and regimented angels’ wings, the interior of the panel shows King Richard II kneeling in prayer while St. John the Baptist and two patron saints of the royal family commend him to the Holy Virgin and Christ Child, who are situated in a flowery paradise surrounded by angels.

This work will be on view March 8–June 22, 2025

Uccello, Saint George and the Dragon, c. 1470

Paolo di Dono, known by his nickname Uccello—“bird” in Italian—was an early-Renaissance artist striving to master the art of visual perspective in paint. Many cite The Battle of San Romano (1438–40), also in Room D, as the finest work by Uccello at the National Gallery, but Saint George and the Dragon shows much more flair. The San Romano scene demonstrates how Uccello was working out perspective, with the orthogonal lines of spears and other weapons clearly marking out a grid the artist could populate with horses and a marvelously foreshortened knight lying face down, but the overall work is not as refined, nor does it feel as finished, as Saint George and the Dragon, hanging just a few feet away. Though smaller, this canvas shows a more sophisticated understanding of space. Uccello here managed to use less pronounced visual elements to create his perspectival grid, achieving a landscape with real depth.

On view in Room D

Sandro Botticelli, Venus and Mars, c. 1485

The lovely thing about Botticelli, an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance, is that unlike the innumerable artists painting biblical scenes in the 15th century, he enjoyed portraying polytheistic deities—as in this painting of Venus and her lover Mars, both Roman gods. Here we see a delightfully down-to-earth narrative, in which a plump, toddler-like satyr blows a conch loudly into the sleeping Mars’s ear while three others muck about with his armor. Far from chiding them, Venus seems lost in thought. The work, recently on loan as part of the National Treasures program to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, does not go back on display until the grand rehang in May. If you visit earlier, there’s a wonderful, smaller Botticelli in Room D, Mystic Nativity (1500), which combines contemporaneous politics with Nativity and paganistic elements.

This work will be on view starting in May 2025 in Room D

Leonardo da Vinci, The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist, c. 1506–08

This astounding charcoal and chalk drawing by High Renaissance artist, inventor, and theorist Leonardo da Vinci, is one of the most magical of his works. Also called The Burlington House Cartoon, it had been looked after by the Royal Academy of Arts since the 18th century but was set to leave the United Kingdom when the RA put it up for auction in 1962. Luckily, the National Gallery launched a public appeal on March 30 of that year for £800,000 (about $1 million)—still thought of as a colossal sum for any artwork, let alone a drawing made on eight sheets of paper glued together. On July 31, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan announced that a special government grant of £350,000 would rescue Leonardo’s work for the nation. And thank goodness it’s on view in a public collection. The almost palpable warmth between the two women depicted is countered by the looseness of the materials that Leonardo used; it’s as if the figures could disappear at any moment. Ironically, before the May rehang, you can see the work at the Royal Academy of Arts, in Burlington House, down the road (November 9, 2024–February 16, 2025).

This work will be on view starting in May 2025

Jan van Eyck, The Arnolfini Portrait, 1434

The Arnolfini Portrait is one of early Netherlandish painter Jan van Eyck’s masterworks. Every item of dress in it presents sartorial elegance without flashiness; the couple’s clothes are expensive and fashionable but there’s no real bling. It’s a highly structured setting, yet the informality of some elements—oranges scattered, clogs strewn aside, slippers in the background—suggests the subjects may have been friends of the artist, and indeed we can see Van Eyck and his assistant reflected in the convex mirror on the far wall. For many years it was thought to portray a wedding, but it is now thought to be simply a double portrait. Oh, and the woman isn’t pregnant, she’s just holding her multilayered skirts off the floor.

On view in Room 28

Raphael, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c. 1507

Italian High Renaissance painter Raphael’s work has been intrinsic to the National Gallery since Portrait of Pope Julius II (1511), on display in Room 12, entered the original Angerstein Collection in 1824. However, in Room 26 you can view his Saint Catherine of Alexandria, a more signature work that captures the saint in religious ecstasy, lips parted and hand on heart. In a triangular composition typical of the high Renaissance, Catherine is shown cloaked in flowing, naturalistic robes with her head twisted away from her body. Catherine of Alexandria was a 4th-century princess who was converted to Christianity by a desert hermit and, in a vision, underwent a mystic marriage with Christ. When she would not renounce her faith, the Emperor Maxentius devised an instrument of torture consisting of four spiked wheels to which she was bound, but a thunderbolt destroyed it before it could harm her. Catherine was later beheaded. This captivating work encapsulates the femininity and fragility of its subject.

This work will be on view starting November 27, 2024, in Room 26

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533

At first glance, the object floating in the foreground of this painting is a mystery. But viewed from a very oblique angle, it’s a skull. It’s one of the more striking features of The Ambassadors, a painting by northern Renaissance master and King’s Painter to Henry VIII, Hans Holbein the Younger. The pictured Tudor noblemen were Jean de Dinteville, left, who was on his second diplomatic mission to England on behalf of France’s King Francis I, and his pious friend Georges de Selve, right. Dinteville was one of Francis’s most trusted courtiers and had attended the wedding of King Henry VIII to his second wife, Anne Boleyn, in 1533, the same year this work was painted. The portrait alludes to the political unrest of the time through the misalignment of scientific instruments on the upper shelf. On the lower shelf a book is open on a page beginning with the word dividirt, meaning “let division be made,” a reference to the religious schism in Europe caused by England’s split from Rome. The lute’s broken string symbolizes discord, while the music book is open on a hymn to the Holy Spirit, perhaps invoking ecclesiastical reunification. Dinteville had described himself as “melancholy, weary and wearisome,” and perhaps his mood inspired the painting’s memento mori in the form of an anamorphic skull.

On view in Room 12

Titian, Diana and Actaeon, 1556–59

Painted in the 1550s for Prince Phillip, later Phillip II of Spain, Diana and Actaeon is one of six large mythological paintings that the Italian Renaissance master Titian based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses. This work, jointly bought for the United Kingdom by the National Gallery and the National Galleries of Scotland in 2009, shows why Titian is so important: he unlocked a new level of realism and movement in his art. See how the young hunter Actaeon brushes away a curtain hiding the secret bathing spot of Diana, goddess of the hunt, and her virginal nymphs. Though some of the nymphs look surprised, some don’t. Perhaps that’s because Titian may have at times used courtesans as models for his character studies. Diana, trying to cover herself with a veil, looks outraged, and it won’t be long before she will turn Actaeon into a stag and set her hounds on him.

On view in Room 29

Anthony van Dyck, Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, c. 1638–39

In 1940, during the Second World War, Prime Minister Winston Churchill ordered that the National Gallery’s collection be buried “in caves and cellars” to escape the predicted carpet bombing from Hitler’s Luftwaffe. And so they were, including this enormous work by King Charles I’s court painter, Anthony van Dyck, depicting the king on horseback, resplendent and ready for battle. Charles I was a great patron of the arts, holding many important works in his collection, some of which also now reside at the National Gallery. But back to the top-secret wartime evacuation of the gallery’s 2,000 works: Experts scoured the country for a hiding place until they found Manod Quarry in Gwynedd, Wales. With a cavernous space at its heart covered with hundreds of feet of slate and granite, the mine was virtually impregnable to bombing. But the Equestrian Portrait of Charles I, at 12 by 9.5 feet, was too tall for its carrier truck to navigate around a tight S-bend. The road had to be dug deeper to lower the truck by a few inches, and to this day the curb in that section is noticeably higher.

On view in Room 21

Johannes Vermeer, A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal, c. 1670–72

“The Sphinx of Delft” is the nickname that the art historian Théophile Bürger gave the Dutch painter Vermeer when he discovered the artist in the 19th century, alluding to the enigmatic presence of people in his works and how elusive he was as an historical figure. This painting and what is thought to make up its partner piece, A Young Woman Seated at a Virginal (also from c. 1670–72, and also in Room 19), display Vermeer’s typically still interiors with characterfully aloof people within them. These two paintings seem to make a pair describing virtue and loyalty in the standing young woman and perhaps promiscuity and flirtation in her seated counterpart, an interpretation given weight by the painting in the background, which depicts a prostitute flirting with clients.

On view in Room 19

Canaletto, A Regatta on the Grand Canal, c. 1740

By the end of the 17th century, it was popular for young noblemen to go on a “grand tour” of Europe with the aim of furthering their artistic education. And every so-called “grand tourist” worth his salt would go to Venice and pick up a painting by the Venetian School artist Canaletto. Canaletto pounced on this as a lucrative business opportunity and (with the help of his studio workers) started knocking out picturesque scenes such as this one for touring aristocrats to snap up. Depicting the February regatta celebrating the Feast of the Purification of the Virgin, the painting captures a traditional Venetian event, making it a perfect souvenir. It is one of the most detailed versions the artist made of the same scene, but he produced many others. Once whisked off home, such a work could be used as proof of one’s attendance at the affair, even if one had missed it entirely because of a dreadful hangover.

On view in Room 33

William Hogarth, Marriage A-la-Mode: 2, The Tête à Tête, c. 1743

Part of the National Gallery’s founding Angerstein collection of 38 paintings, the six canvases in English artist and satirist William Hogarth’s “Marriage A-la-Mode” series offer a morality tale of the disastrous consequences of wedding for money rather than love. Focusing on a couple whose marriage has been arranged by their fathers for titles and cash, Hogarth’s series, rife with symbolism throughout, is viscerally disturbing. The husband contracts syphilis from his extramarital exploits, and the wife takes a lover. The story comes to a climax as the wife’s paramour stabs to death the weakened, syphilitic husband. In the final scene, the wife takes a fatal dose of laudanum when he is hanged for murder. In this, the second of the six paintings, a clock shows that it is past noon. The wife is taking a late breakfast as her husband slumps in a nearby chair. It appears they’ve both had a wild night, but—judging from the damp spot on the wife’s skirt and the woman’s nightcap stuffed in her husband’s pocket—not with each other.

On view in Room 34

Joseph Wright of Derby, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, 1768

Eighteenth-century English portraitist Joseph Wright of Derby is perhaps better known for having given scenes of scientific and industrial advancement an importance traditionally reserved for historical and religious subjects. This painting about the pursuit of scientific knowledge in the Age of Enlightenment doubles as a commentary on the fragility of life. A traveling lecturer conducts an experiment in front of an private audience of aristocratic viewers, showing how a bird will suffer (and perhaps die, unless the lecturer has mercy on it) in a vacuum. Dramatically illuminated by a candle, the onlookers are variously distressed, distracted, and absorbed as the bird struggles for air. It has been noted that while this experiment was conducted at the time on a range of animals, birds, and insects, the bird depicted here, a rare white cockatiel, would likely not have been used in in such a way (unless it is, in this fictional drama, a family pet). Although the implied value of this particular animal may constitute a nod to the preciousness of all animal’s lives, Wright leaves that determination up to the viewer.

On view in Room 34

Thomas Gainsborough, Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, c. 1750

Also in Room 34 is this image of a husband and wife by the quintessentially British painter Thomas Gainsborough. Born and raised in Suffolk, Gainsborough worked mainly in London, where he became a founding member of the Royal Academy of Arts. Most people think of Gainsborough as a portraitist—one of whose great rivals was Joshua Reynolds, on display in the same room—but what he really enjoyed was landscape painting. To create his bucolic English countrysides, Gainsborough would often use broccoli for trees and lumps of coal for rocks to study placement and composition. The subjects of Mr. and Mrs. Andrews, an Essex squire and his wife, posed for Gainsborough under an oak tree at the point where their house’s lawn met their farmland. The unpainted patch in Mrs Andrew’s lap is a mystery; some think it could have been intended for a pheasant shot by her husband, while others think it was reserved for the addition of a baby later on.

On view in Room 34

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821

After being on loan to the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, this painting is back at the National Gallery, reappearing in a display dedicated to its creation. Depicting an idyllic rural landscape just minutes away from where the artist grew up in Suffolk, it belies an altogether more foreboding reality. Constable composed this pastoral vision when the truth of what was happening in the English countryside was quite different: steam trains had begun coursing through the landscape and poverty-stricken farmworkers were quickly being replaced by mechanized equipment. The Hay Wain portrays an England already of the past, an idealized view of what once was.

On view in the Sunley Room through February 2, 2025

J. M. W. Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed: The Great Western Railway, 1844

In stark contrast to Constable, his contemporary J. M. W. Turner was all about crystallizing modernity. This painting celebrates the achievement of the British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel and his Great Western Railway, but it also pits human technology against nature, here in the form of a hare. To the left of the central image of a train barreling toward us is a small boat on a river far below, and to the right is a man driving a horse-drawn plough, both much slower than the train. Even so, steam trains at this time, while the height of technology, would likely only reach a speed of about 33 mph, so it is in fact the hare running ahead of the train that is the fastest. Unfortunately, it’s hard to see the hare in the painting nowadays because Turner swiftly added the animal the day before the painting was exhibited, and the paint has become virtually transparent over time. (Luckily, it is captured in an engraving by Robert Brandard that is held by the Tate.) On display in the same room is Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire (1839), depicting the old oak warship being hauled to the scrapyard by a newfangled steam-powered tug. In this work, the sun—embodied by the multi-colored sky—is literally setting on the age of sail.

On view in Room 34

Claude Monet, Bathers at La Grenouillère, 1869

If you’re mad keen on French Impressionist Claude Monet’s paintings of water lilies, head to Room 41, but please also seek out his more exciting Bathers in Room 44. This masterful composition, an iconic work that brought painting forward by leaps and bounds, shows members of modern society relaxing in the then popular Parisian suburb of La Grenouillère. It was only in 1874 that the Impressionism movement was founded, so this can be seen as an influential forerunner. Monet’s asymmetrical composition, his use of complementary colors—influenced by Michel Eugene Chevreul’s 1839 color wheel—and his depiction of a scene “en plein air” all contributed to the artistic movement to come. Don’t miss Monet’s other works in this room, plus Edouard Manet’s Execution of Maximilian (c. 1867–68).

On view in Room 44

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884

Breaking down color and light into separate dots of pigment, French painter Georges Seurat depicted a different suburb of Paris on the River Seine in his mammoth painting Bathers at Asnières. The inventor of the post-Impressionist style of pointillism, Seurat was essentially experimenting with how color mixed in the viewer’s eye. Look closely and you’ll see that every square inch of the painting is made up of hundreds of dabs of different hues, which all coalesce into as scene of impending modernity (note the factories belching smoke in the distance). Look around the same room for another leap forward in Paul Cezanne’s works Hillside in Provence (1890–92) and Curtain, Jug and Dish of Fruit (1893–94).

On view in Room 43

Henri Rousseau, Surprised!, 1891

An all-time favorite of gallery visitors, this painting by naïve—or primitive—French artist Henri Rousseau captures an imaginary scene of a tiger in a lightning storm. Rousseau never left France (the flora and fauna in his works were based on travel books and trips to the Jardin des Plantes in Paris) and was what we might call a “Sunday painter” until he retired from his job at age 49 to make art full time. His talent was recognized during his lifetime though, when the artist Félix Vallotton wrote, “His tiger . . . ought not to be missed: it is the alpha and omega of painting . . . . As a matter of fact, not everyone laughs, and some who do are quickly brought up short. There is always something beautiful about seeing a faith, any faith, so pitilessly expressed.” Recently the focus of a month-long kids’ program at the National Gallery, the work continues to inspire, and the question remains, is the tiger—who here seems as startled as a house cat by the lightning—or its intended and offscreen prey who is actually the surprised party?

On view in Room 41

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888

Dutch post-Impressionist Vincent van Gogh painted four versions of Sunflowers in just one week, in anticipation of a long-awaited visit from a supposed friend, the painter Paul Gauguin. “I am painting with the gusto of a Marseillaise eating bouillabaisse,” Vincent wrote to his brother Theo. The yellow sunflowers symbolize happiness and stand in for the sun-drenched fields of Provence, where the artist was living, but the joy this painting was meant to bring was, for the artist, quashed by his subsequent quarrels with Gauguin. At least we can still appreciate how Van Gogh described them in a letter to the painter Émile Bernard in 1888: “Raw and broken chrome yellow will blaze forth on various backgrounds, blues between pale véronèse [emerald green] and royal blue, framed with thin strips painted in mine orange [red lead pigment].”

On view in Room 6

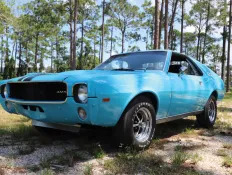

The AMC AMX Is Still the Best-Kept Secret in American Muscle Cars

Richemont First Half Sales Decline 1% in Rocky Times for Luxury

Exclusive deal: Buture VAC01 cordless vacuum has a massive 67% discount

10 Reasons Why GOP Takeover Won’t Stop College Athletes as Employees