Courtesy Jean-Claude Marquet/SWNS

Along the walls of a cave in central France are the oldest identified markings made by Neanderthals more than 57,000 years ago, according to a recent study published in the scientific journal Plos One.

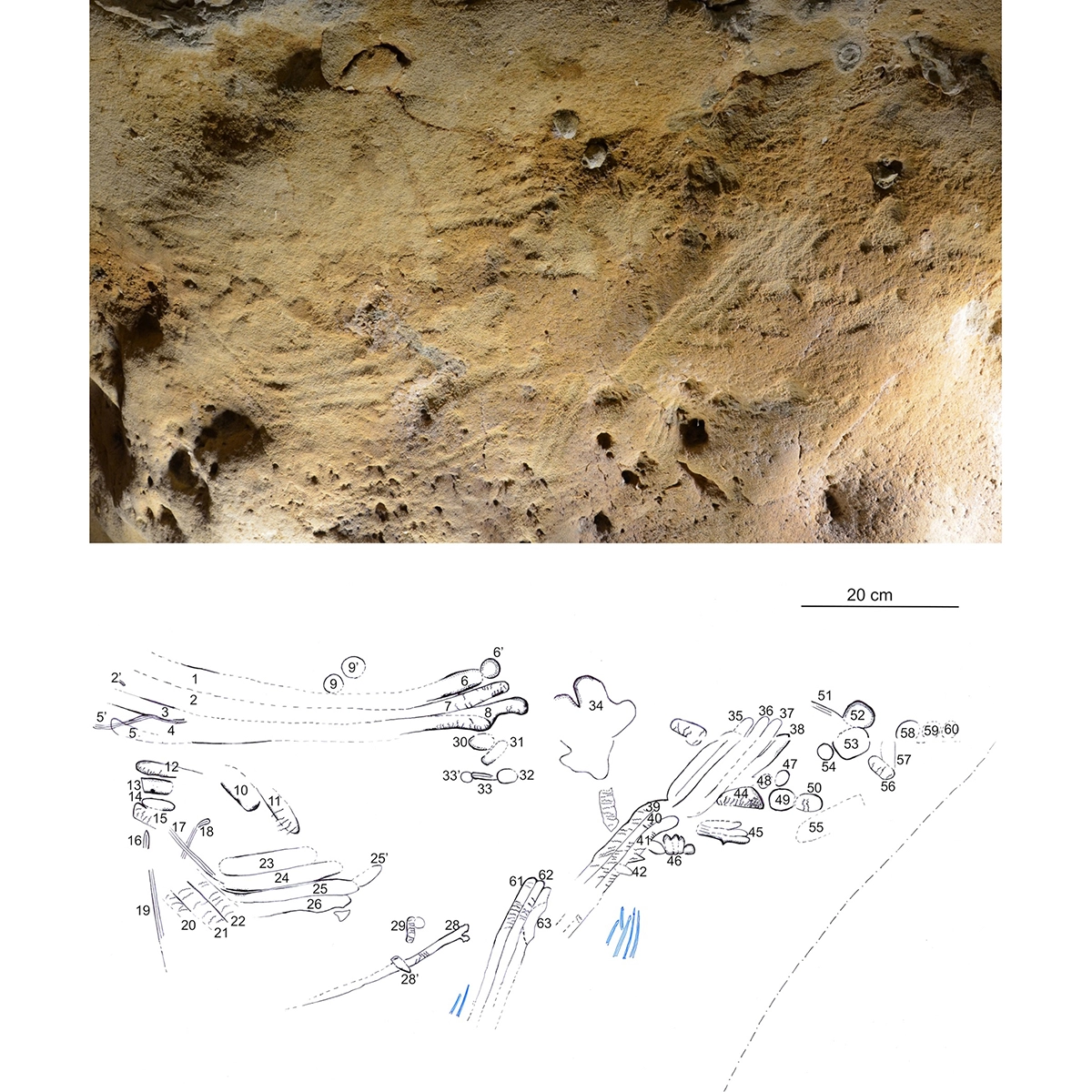

Scientists analyzed hundreds of wavy lines, dots, and faint striations—known as finger flutings—left on the longest and most even wall of an ancient cave in La Roche-Cotard in the Loire Valley.

In 1846, the cave’s entrance was uncovered during nearby quarrying work. In 1912, animal bones and Neanderthal stone tools were found during an excavation. The full scope of the cave has since been realized through more extensive digging conducted in the 1970s and, again, from 2008 until now.

Within the cave, four primary interconnecting chambers plunge more than 108 feet into the riverbank. Based on where scientists found the tools and bones, they believe that the Neanderthals lived in the first chamber and in front of the cave entrance.

Scientists analyzed sediments that blocked the entrance, which indicated that the cave had been externally sealed at least 57,000 years ago—thousands of years before the arrival of modern humans in the region 42,000 years ago. This, along with the tools discovered at the site, suggests that only Neanderthals could have made these finger flutings within the cave.

The markings seem to have been made by Neanderthals sweeping and pressing their fingers across a thin brown film on the limestone walls. The height of the engravings could have only been made by tall teenagers or adults. The patterns are grouped into eight separate panels, though it is unclear what they mean.