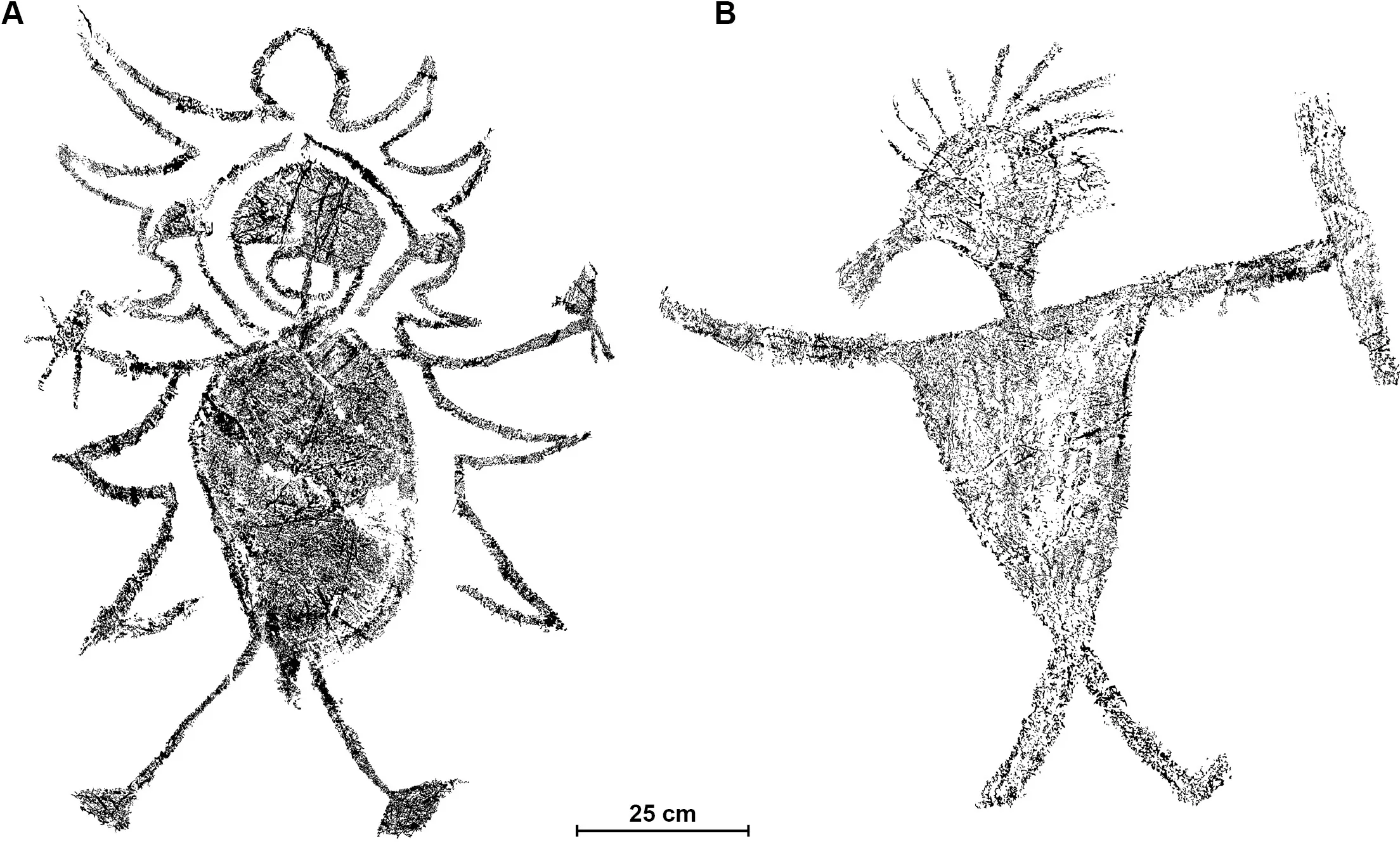

Courtesy PLOS One.

Recent radiocarbon dating of rock art in Malaysia’s Gua Sireh cave complex is offering unprecedented insight into a generations-spanning saga of Indigenous resistance to hostile civilizations.

A team of Australian scientists used radiocarbon dating to conduct what they have hailed as the first chronometric age study of Malaysian rock art. Their findings were first reported on Wednesday in the peer-reviewed science and medical journal PLOS One.

The study helps illuminate “the social contexts of the Gua Sireh art production, as well as the opportunities and challenges of dating rock art associated with the Malay/Austronesian diasporas in Southeast Asia more generally,” the team wrote.

The cave system is home to large charcoal drawings of human figures made by the Indigenous Bidayuh people of the Sarawak region, now known as Borneo. They paint a dramatic scene: the towering figures brandish knives or spears, and wear elaborate headdresses. The Bidayuh did not maintain a written record of their history, making the cave art a precious—if worn—guide to their varied (and tense) geopolitical position.

More than 300 images decorate the walls, however the team focused on two anthropomorphic figures: one, identified as GS3, has a round torso and wears what looks like a jagged cloak or long, plumed headpiece. The other figure, called GS4, has a triangular body and is sparsely adorned, save for the sheathed knife in their right hand. Smaller figures surround the pair, suggesting they may symbolize “big and/or powerful warriors”, according to the study.

The radiocarbon dating estimates GS3 was created between 1670-1710 while GS4 dates to 1800-1830.

“When the older anthropomorph was drawn, the Bidayuh were dominated by Malay elites, whereas the second large anthropomorph would have been made during a period of increasing conflict between Bidayuh and both Iban and Brunei Malay rulers,” the scientists wrote. “During this period many Indigenous Sarawakians moved into the upland interior, including the Gua Sireh area, to escape persecution.”

The study further posits that despite their approximately 160-year age gap, both artworks were likely produced during periods of conflict, given the prominence of weaponry and other battle adornments.

“The radiocarbon age determinations reported here sit neatly alongside other recently published numeric ages for the distinctive black drawings associated with the migration of Austronesian people across Southeast Asia,” the researchers said.

The Bidayuh people occupied present-day Borneo for some 2,000 years and, per historical records, flourished in relative autonomy until a 200-year period when the region was governed by Malay’s Brunei Sultanate. Per historical records, the Indigenous people suffered exploitation and violence under the long rule. During that period, Bidayuh tribes also clashed the Iban, another Indigenous group, over territory.

Researchers also pulled artifacts from the cave, which were used to corroborate their radiocarbon dating, as well as further illuminate histories of the Bidayuh and neighboring people. A group of artifacts from the Gua Sireh excavations are on display at the Sarawak State Museum in Kuching in Borneo.