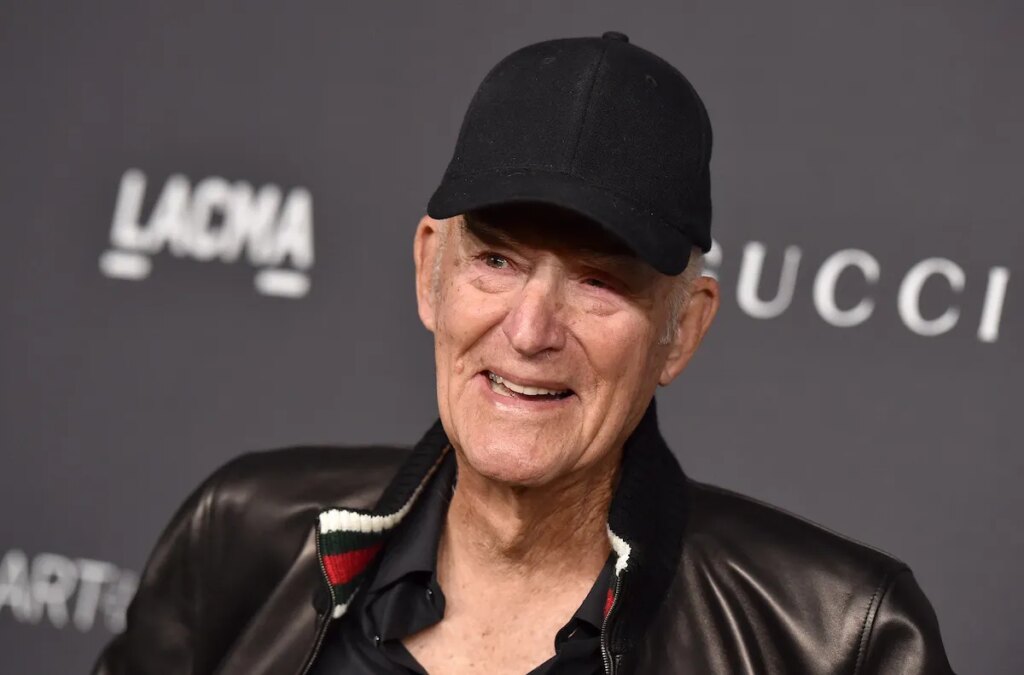

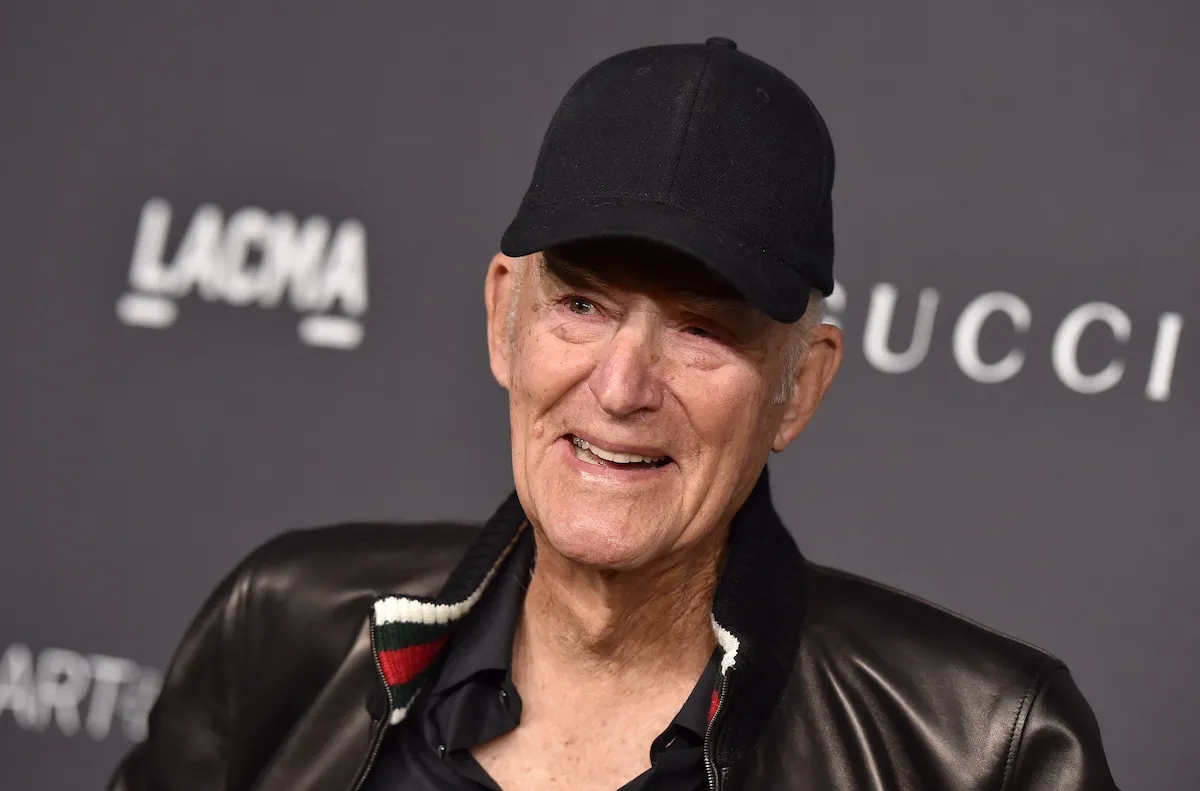

Robert Irwin, an influential Light and Space sculptor whose installations reoriented how viewers perceive a space, at times transforming the institutions that hold them in the process, has died at 95. According to the New York Times, the cause was heart failure.

Many of Irwin’s barely-there artworks are spare and elegant, with lighting tubes and scrims acting as some of the recurring elements across his oeuvre. His sculptures and installations do not appear static, like most other artworks. They seem to shift—albeit subtly—depending how and where they are seen, and they tend to gently mess with viewers’ senses of perception.

When Irwin began to produce this kind of art, during the ’60s and ’70s, Minimalism was in vogue on the East Coast, and site-specificity—the way that an artwork dialogued with the parameters of the space in which it was set—was considered paramount. Irwin, who was part of a California movement known as Light and Space, took a different tack, producing work that he said was neither site-specific nor, as he put it, “site-dominant,” in that it did not overwhelm a gallery. Rather, he strove for what he called Conditional Art.

His 1970 project for the Museum of Modern Art kicked off a series of scrim works that would become some of the defining works of the era. Part of the piece consisted of a nylon scrim drop ceiling. That was its most obvious component—other, less noticeable elements included shifts in the gallery’s lighting and a wire stretched before a wall. “Using nylon scrim and wire and with adjustments of light,” its short press release noted, “Irwin activates our awareness of the physicality of volume and intensifies our spatial perception.”

He would do something similar with Scrim veil—Black rectangle—Natural light, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (1977), one of the most iconic works ever realized at that institution. It featured a scrim run across a gallery of its former Marcel Breuer–designed home and utilized the sunlight that poured in through a window, illuminating just a portion of it. Most of the people who saw it didn’t know what they were viewing. “People would step out of the elevator, say, ‘Hmm, empty room,’ and hop back in before the doors shut,” Irwin told the Times in 2013, when the work was restaged at the Whitney.

Irwin’s ambitions continued to grow. Similar works involving lighting effects and scrims were staged at institutions such as New York’s Dia Art Foundation, which, in 1998, mounted an 18-room structure whose walls were formed from fabric. When that piece was restaged in 2015 under a new title, Irwin said, “The thing is not frontal, not linear, not sequential, there’s no beginning, middle or end. You could, essentially, enter anywhere.”

“In my long career, I have been privileged to work with some of the greatest artists of the 20th century and develop deep friendships with them, but none greater or closer than Robert Irwin,” said Arne Glimcher, founder of Pace Gallery, which represents Irwin. “In our 57-year relationship, his art and philosophy have extended my perception, shaped my taste, and made me realize what art could be.”

Robert Irwin was born on September 12, 1928, in Long Beach, California, to a father who owned a contracting business. After attending school in Los Angeles, Irwin joined the Army in the late 1940s and spent time in Europe. But his heart was in California, and he would eventually return to LA to attend a series of art schools.

By 1957, Irwin had begun working in an Abstract Expressionist mode, producing paintings that were “really fucking bad,” as he told Apollo in 2015. He came out of the ’50s an entirely different artist, one far more committed to his craft. He showed some of these painterly abstractions at Ferus Gallery, the taste-making LA gallery with an offbeat sensibility that would go on to foster Larry Bell, Andy Warhol, Billy Al Bengston, Ed Ruscha, and other artists.

During the ‘60s, Irwin’s work took a turn toward the minimal. His abstractions were pared down to a bunch of lines in varying colors, then stripped back even further, until all that was left behind were a lot of dots that fused in the mind’s eye to form shapes.

And then, having reduced painting to its basics, he began to play with the very nature of the canvas itself, producing convex works made of aluminum and plastic. When seen in a gallery, these works would sometimes blend into the wall, only to stand apart from it due to shadows thrown against its support by the space’s lighting.

The plastics Irwin used were produced at an LA auto body shop. Like Bell and other Light and Space artists, Irwin invested himself in materials quite unlike rarified oil paint and stately canvases. As his art journeyed ever further in strange and new directions, he stopped producing what looked like painting altogether, turning his art sculptural.

The scrim pieces, like his plastic ones, had their roots in industry and mass consumption. While on a trip to Amsterdam, he fell hard for the window shades that were ubiquitous there. He decided he had to have that element in his art, and would continue to rely upon it for many years after.

Between the 1970s and the 2010s, Irwin’s art grew bigger and more ambitious. He designed a garden for the Getty Center in Los Angeles that was completed in 1998 and is comprised of circles within circles of plants. It doesn’t hold any sculptures, but it contains that same Irwin attention to space and perception that recurs throughout his objects.

Some projects, such as one intended for Miami’s airport, were simply too grand and were never realized. Yet others were epic and were ultimately brought into the world, though not without difficulty.

Working alongside OpenOffice architects, Irwin served as the designer of Dia:Beacon, the Upstate New York home of many large-scale installations owned by the Dia Art Foundation. The move was an unusual one—most museums are conceived by professional architects with sizable firms—and Michael Govan, the foundation’s former director, has said he initially faced pushback on the idea. Yet the building, set in an abandoned Nabisco factory, is now considered a mecca for art lovers, Minimalism obsessives, and day trippers, and is prized for its lighting and its airiness.

Across a career spanning more than a half-century, Irwin scooped up many accolades, including a MacArthur “genius” fellowship in 1984, making him the first artist ever to receive the distinction, and a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1976. He had major exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles and the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid, and appeared in Documenta 4 in 1968 and the 1976 Venice Biennale, for which “he stretched a piece of string into a rectangle that outlined light being filtered through a tree,” as the Washington Post once reported.

Irwin has forever changed some of the institutions that showed his work. The Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, for example, is host to a permanent installation by him made of 115 lighting tubes. Aptly, it is called Light and Space (2007). Sizable works also appear at the Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas.

“Robert Irwin’s passing will be felt across the art world and is especially poignant in our community and at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego,” said the institution’s director and CEO, Kathryn Kanjo. That museum has the vastest Irwin holdings of any institution worldwide, with 55 pieces in its collection.

Robert Irwin: A Desert of Pure Feeling, a feature-length documentary about the artist, just began streaming in the US last week.

Interest continued for his work right up through a 2020 Pace Gallery exhibition that he called his “swan song.” Queried about the late-career rush of attention, a humbled Irwin told the Los Angeles Times, “Am I having a moment? No. I’ve been here all my life.”