Ida Applebroog, a feminist artist with an unerring eye toward power, has died at 93. Her death was confirmed by her Hauser & Wirth, which represented Applebroog since 2009.

Over six decades, Applebroog’s practice shifted between painting, sculpture, film, and photography. She was a monumental presence in America’s feminist art movement, with an oeuvre fascinated by bodies, many pictured in domestic settings, in ambiguous couplings and groupings. Under her uncompromising gaze, interaction was a game dictated by violence and gender.

In her paintings, people are reduced to graphic, dripping outlines or lonely, disembodied genitals. For the 2012 edition of Documenta in Kassel, Germany, she presented a series of photographs in which women brandish signs that read “FIRST ENSLAVE MANKIND”; the poster is propped between the open legs of a woman who smiles at passerby.

“Her emotionally disruptive and fearless approach to making art has been an inspiration to many generations, intensely personal, honest and raw,” Manuela Wirth, President Hauser & Wirth, said in a statement. “We are eternally grateful for her humor, wit and radical introspection, presenting the absurdities of life as it is. Our thoughts are with Ida’s children and her extended family and friends at this time. She will be deeply missed by so many.”

Ida Applebroog was born Ida Applebaum in 1929 in the Bronx, New York, to ultra-Orthodox Jewish parents from Poland. It was not a happy household, she said in Call Her Applebroog, a 2016 documentary shot by her daughter, the filmmaker Beth B. Applebroog’s father was a strict authoritarian and told her she “should not behave like the Yankees,” meaning Americans. “I learned very early on how power works,” she said.

As a child, she retreated inward (“Silence was very, very nurturing,” she recounted in the film) and found comfort in art, including repetitive drawings of her own body in the bathtub. In 1948, she began studying graphic design at the Institute of Applied Arts and Sciences, and as a student worked as the only woman at an advertising firm. She said she experienced sexual harassment there, and quit after six months to work as a freelance illustrator.

In 1950, she married her high school sweetheart, Glenn Horowitz, and took his last name. However, she later changed it again to Applebroog (she had “no idea” where “broog” came from, she said). The two had four children by 1960, after which they relocated to Chicago, where, between 1965 and 1968, she attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

The following decade brought personal hardships and her breakthrough in the art world.

In 1968, her family again relocated to San Diego. California was an ill fit for Applebroog, and she struggled to make a name for herself, even as she completed her first vital body of work: 150 ink sketches of her naked crotch made in the bathroom. Her motivation was obsessive and exploratory, but not sexual, she once said. This ritualistic looking, she hoped, would uncover the bits of herself “hidden away.” The drawings were not publicly displayed until her first solo exhibition at Hauser & Wirth New York, titled “Monalisa,” in 2010.

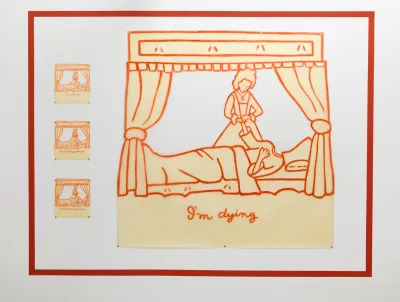

She caught the attention of New York’s creative community in the mid-1970s through a series of intimate self-published books she called “Stagings” that contain identical cartoon drawings. The tomes were reminiscent of flip books; she mailed them to artists and writers. Her involvement with the feminist movement in the US began after attending the Feminist Artists Conference at the California Institute of the Arts in 1972. In 1974, she returned to New York, and later joined the Heresies Collective, which included figures such as curator Lucy Lippard and artists Joan Snyder and Pat Steir.

While contributing to the collective’s publication Heresies, she developed her signature drawings—bold, cartoonish figures on Rhoplex-coated vellum. These characters were presented stripped of narrative details, and were often framed by windows or screens, like phantoms of a ruined household.

Applebroog was represented by Ronald Feldman Fine Arts from 1981 for roughly 25 years. In 2009, she joined by Hauser & Wirth.

Throughout the decades, she exhibited extensively across the US and Europe. Among the works she produced during this time were Modern Olympia (1997–2001), a feminist take on Manet’s painting, and “Photogenetics” (2005), a series of mixed-media portraits created through an experimental meeting of clay modeling, photographing, painting, and printing. The resulting faces are ghoulish; they look like a mangled spirit turned inside out.

Monalisa (2009), the installation from which her Hauser & Wirth debut took its name, is a house with translucent shingles and panels made of sourced imagery. Where a window could be, is a portrait from “Photogenetics”.

Art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson wrote in the essay accompanying the show, “In the ‘Monalisa’ project, as in Applebroog’s past work, the home is not a stable location but an unfixed nexus of sexist violence, perversion and thwarted safety, as well as tenderness, secret stolen moments, bodily pleasure and honest labor.”

Applebroog’s art was shown at the Brooklyn Museum, the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, Texas, and the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. A retrospective was held at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid in 2021. Her works are owned by the Whitney Museum, the Guggenheim Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, among many other institutions.