One’s eye typically skates right over the list of materials on the caption for an artwork, since the verbiage used—“oil on canvas,” “ink on paper,” and the like—tends to be more perfunctory than it is engaging. But in the case of Ruben Ulises Rodriguez Montoya’s sculptures of creatures in transformation, the words used to describe his many materials cannot be ignored because they are so stylized and so bizarre.

Take the case of The Lil Rat That Made It on Board the Ship (2021), a sculpture that appeared at Artists Space in New York this past summer. It’s an all-black assemblage that has a long, gnarled tail extending from its body and a pointy claw affixed to its head; it would not be out of place in the Alien universe. Its materials, as described by Montoya, are worth quoting at length: “My very very large black t-shirt that I smeared with pigmented dragon skin silicone. Welding wire, black zip ties, black and green sewing string, rabbit pelt, horn tips, half a horn, nail polish, dirty socks because Timoh was washing his calzones and I couldn’t wait, emerald powdered pigment, car fender, black car part, possed bouncing ball.”

Who is Timoh, and what did his boxers have to do with these dirty socks? What black cart part? Why did the artist smear his shirt with silicone, and where does this garment even figure in the work, anyway? Rather than clarifying this “lil rat,” Montoya’s list of materials only adds another layer of mystery—which, of course, is the point.

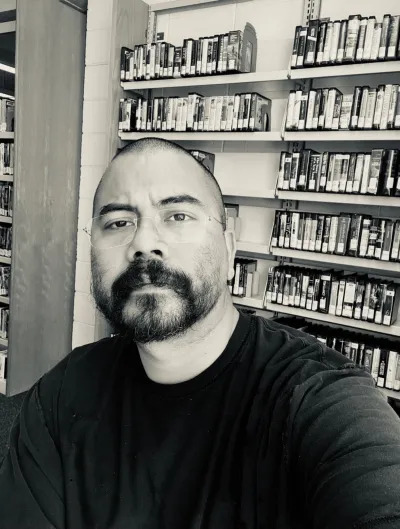

Nahuales, chupacabras, shape-shifters, aliens, and other supernatural creatures figure readily in Montoya’s art, which is often imbued with dense mythologies of his own making. He knows his art may feel foreign or odd to some. “I’m interested in mythology as a way to explain things that maybe can feel uncomfortable to somebody,” Montoya said in a recent interview, speaking by Zoom from his studio in Mexico City.

He was alluding to his true subject matter: how people outside the mainstream, and in particular people along the U.S.‒Mexico border, are viewed as unwanted beasts by those who abhor their very existence. But rather than depicting outright the violence wrought upon migrants or even portraying those individuals themselves, Montoya uses fantastical beings as parallels for the lived realities of people in Mexico, the nation where he was born, and Texas, the state where he long resided before moving back to his home country.

Montoya approaches his art as a horror novelist might. He’s been celebrated by critics and curators for concocting sprawling narratives involving competing life forces and intergalactic travel. Last year he won Toby’s Prize, an award given by the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, where he now has a show that he says is about the “explosion of a vampire that ends up becoming a spaceship itself.”

“The skin shards start to attach to parts of the spaceship,” Montoya said. “And then the vampire starts to suck the energy out of what’s left of the spaceship. And then these little tentacles start to become like more tumors that can expand and expand, and then this starts to sort of create a cyborg, this sort of half-vampire, half-spaceship. And as time goes on and it’s traveling into deep time, this spaceship then starts to mutate and create other beings that can help it.”

Those creatures are composed of wiring, used clothing, silicone, washer parts, and a whole lot more, and they are, according to Montoya, still awaiting a purpose in their world. In that way, he said, they have queer overtones: They are hybrids engaged in the messy process of finding themselves. He called his practice a form of “abject queer fecundity.”

Despite the dark narrative undertones, Montoya’s art is often gorgeous, said Lauren Leving, the curator of Montoya’s Cleveland exhibition. “The work is beautiful, but it can sometimes be approached as abject or grotesque,” she said. “The language of otherness is often thought of as negative, but here it’s absolutely not. That’s so unique. He’s allowing us to think about possibilities for our lives—and for the future.”

A self-described “desert hoe,” Montoya was born in 1989 in the Mexican city of Parral. When he was two years old, he crossed the U.S.‒Mexico border with his mother. According to a text written by the artist, his father would eventually follow, joined by his cousin and chupacabras. “Standing by, waiting for our turn to talk to the immigration agent’s interrogation, I thought of what it would’ve been like to cross the border, not on land or water: but on my grandmother’s broom, under a battalion of stars and the sweet smell of sacred datura,” Montoya wrote. “No documents or fear, just the breeze below our feet. Instead that night, crossing the bridge, we became Coyotes; of both myth and reality.”

Carefully honed fictions became a cornerstone of his life in a different way during his undergraduate years, when he studied Spanish literature at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces. Growing up, he said, he witnessed a form of “heteronormative life that I didn’t really belong to. Capitalism, the labor of a nine-to-five: I never really felt like I fit in with that.” Studying literature was the “easiest way to have some kind of artistic inclination,” and horror and science-fiction books offered worlds beyond this one.

Then, with one semester left until graduation, the artist rafa esparza reached out to Montoya, having been intrigued by the stylized nude photos that Montoya had been taking of himself in the desert and posting to Instagram. With a project in the works at Ballroom Marfa, a space in Marfa, Texas, about four hours from Las Cruces, esparza asked Montoya to help out as an assistant. Montoya accepted and became convinced that sculpture was his true calling. Then he applied to an MFA program at Virginia Commonwealth University and was accepted.

By the time he graduated, in 2020 at the height of the Covid pandemic, Montoya had already been working nomadically, scouring New Mexico, El Paso, and Juárez for materials to use in his art. He recalled living close to the Rio Grande in El Paso and finding objects cast off by construction workers and migrants near the river. As he picked through discarded water bottles and clothes, he found himself “really curious about what [these materials] used to be, and who they belonged to,” he said.

For some, that practice has situated Montoya within a long lineage of Chicano artists who use found objects in their work—a text for his 2020 show at Sargent’s Daughters in New York, for example, labeled his aesthetic rasquache, a reference to scholar Tomas Ybárra-Frausto’s term for an artistic tendency predicated on hybridity and repurposed materials. Yet others have argued that while that may be applicable to Montoya, he stands apart from nearly all of his Latinx colleagues. In Artnet News, Barbara Calderón praised Montoya as “one of few challenging dominant tastes in Latinx art that favor representational, pop aesthetics, or explicit cultural motifs.

“Rasquachismo has a male-centered machismo, which is what Amalia Mesa-Bains was reacting to when she created domesticana, a woman-centered take on it,” said Susanna Temkin, a curator of La Trienal, El Museo del Barrio’s recurring survey of Latinx art, which this year counts Montoya as a participant alongside well-known artists such as Ser Serpas, Roberto Gil de Montes, and Magdalena Suarez Frimkess. “I think we can see, in Ruben, a queer take on it.”

Montoya acknowledged to me that his work could be considered a form of rasquachismo, but he said that his art added “a literal appendage” to that term, turning the concept corporeal. With his art, he wants to create what he calls “material carriers”—to “make a body in order to make something that feels like it’s alive.”

That remark sounds like something that might be uttered by a horror movie character—a Dr. Frankenstein with a social conscience, perhaps. But Montoya said he did not intend to inspire fear. He views his creations as responses to a kind of “American life that is very clinical and very sanitized.” His sculptures are bound to stand out, but we should not cower in the face of them.

“I think if people are scared,” Montoya explained, “it’s because they can see something in the work that’s reflective of them.”

MoCA Cleveland Picks Megan Lykins Reich to Fill Director Role Left Vacant Amid Controversy in 2020

Puppies Puppies Wins Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland’s Prize

Why the Alfa Romeo Giulia Sprint GT Is the Quintessential Italian Sports Car

Les Arts Décoratifs Gets Intimate With New Exhibition

Concept shows Apple Books+ would be a killer addition to Apple One

Money Talks as Mets, Dodgers, Yankees Advance in MLB Playoffs