Given the sprawling regulations dealing with works of art, new developments in art law are complex matters even for the most sophisticated specialists. A sample of opinions from experts in the United States about new art laws, on the other hand, reveals evolving assessments and a surprising consensus. In a series of ARTnews interviews, most experts well-versed in current legal developments point to regulations relating to collecting, especially in the realm of restitutions and ethical retention of cultural property, as a leading edge in US art law.

Below, ARTnews focuses on those developments and others within four areas of art law with which collectors and connoisseurs are advised to be familiar.

KYP (Know Your Provenance)

Provenance investigations in certain areas of collecting rank among the most significant affected by recent changes to US art laws. Legislation such as the US Bank Secrecy Act, passed in 1970 in an effort to combat money laundering, might initially seem irrelevant to such investigations, but when cultural artifacts stolen from the National Museum of Iraq started showing up for sale in the US, Congress began deliberations about potential laundering schemes within the high-end art market. The outcome was a series of amendments to the Act passed in 2021 that classify dealers in antiquities as, in effect, financial institutions covered by the law. The law now requires dealers to monitor and report suspicious activities, such as buyers offering to make large purchases with bundles of cash. Furthermore, dealers who possess or sell artifacts previously smuggled into the United States contrary to federal law may be required to forfeit them—a compelling incentive to investigate and verify an item’s provenance.

Provenance issues play significantly different roles in two major restitution initiatives in the US, one relating to Nazi theft and acquisition of art under duress, the other concerning Native American human remains and cultural heritage. Courts in the US “have recently shown hostility to Nazi-era claims,” according to attorney Nicholas O’Donnell, partner at Sullivan & Worchester and editor of Art Law Report. O’Donnell has represented museums and Holocaust survivors and their heirs in restitution disputes, including the heirs of Jewish art dealers robbed by the Nazis, in a definitive 2020 case before the US Supreme Court. The loot in question was the so-called Guelph Treasure, a collection of medieval Christian relics valued at $250 million held by Germany’s Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The German government rejected a series of restitution claims by the dealer’s heirs. The heirs, two of whom are US citizens, then recruited O’Donnell to file a lawsuit on their behalf under the 1976 Federal Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA). FSIA actually precludes lawsuits against sovereign foreign governments, but with a few specific exceptions. Among those exceptions are cases in which “rights in property are taken in violation of international law.” O’Donnell argued that, since genocide violates international law and the forced sale of the Treasure took place in the context of a genocidal attack on Jewish people, US courts could sue the German government. After lower courts upheld O’Donnell’s argument, the German government appealed to the US Supreme Court, arguing that when a government takes property from its own citizens, the case is a domestic issue, not a matter of international law. The court ultimately sided with Germany and dismissed the case.

This ruling shifted an entire legal field in the US, according to O’Donnell, because it “foreclosed a huge category of cases against sovereign defendants who are in possession of Nazi looted art. It effectively swept away claims by German Jewish victims who were within the territory of Germany.” Because the Supreme Court endorsed the so-called “domestic taking rule,” US courts “won’t hear restitution cases at all if the claimant was a German Jew. That’s the law now.”

In apparent conflict with O’Donnell’s statement is the September 2023 announcement reporting the largest case of Holocaust art restitution in the United States. In September and again in July 2024, artworks by Egon Schiele were returned by the Manhattan District Attorney’s office to the heirs of Fritz Grünbaum, a Jewish cabaret performer and art patron who was arrested in Germany in 1938 and died in the Dachau death camp. For more than a quarter century the Grünbaum heirs argued unsuccessfully for the return of Schiele artworks in civil suits in state and federal courts. In 2018 a New York court accepted evidence that Mr. Grünbaum never sold or surrendered art from his collection before his death, making his heirs their true owner.

Provenance records also revealed that several of the Grünbaum Schieles were purchased by New York art dealer Otto Kallir, who sold them to a number of private collectors and museums. New York, like most states in the US (except Louisiana) holds that even a good faith purchaser cannot acquire a valid title from a thief. The heirs subsequently contacted the Manhattan District Attorney’s office asking for an inquiry about whether Schiele paintings once owned by Grünbaum and now in New York or handled by Kallir’s gallery would qualify as stolen property under New York law. The DA’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU) found evidence of theft. After several museums and private collectors gave up their ownership claims, an outcome the heirs were unable to reach through the courts, the Schiele artworks were returned to the Grünbaum heirs. Laws covering stolen art are not new, but the investigations conducted by the Manhattan ATU, led by assistant district attorney Matthew Bogdanos, have set new records for restitution. Since its creation in 2017 the Unit has recovered approximately 5,800 stolen objects for repatriation to countries all over the world.

Repatriation of Indigenous Art and Artifacts

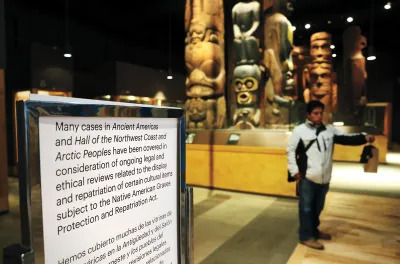

Provenance evidence must not only be redefined, but reimagined, in the implementation of new rules issued in January for the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Congress passed this unprecedented human rights law in 1990, mandating that museums and federally funded institutions (including universities) return Native American human remains, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony wrongly taken from tribes, Native Hawaiian organizations, and lineal descendants. The legislation required museums to review their collections and consult with federally recognized tribes. Over time, a lack of strict deadlines and debates about material qualifying for return inhibited timely resolutions. The new regulations clarify rules and time lines and, most significantly, direct museums to defer to a tribal nation’s knowledge of its customs, traditions, and histories when making their repatriation decisions.

Attorney Richard West, a citizen of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma and founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, offers a uniquely informed perspective on the history of NAGPRA and its relationships with museums. “To begin with the big picture,” he explains, “the original legislation set up a framework both general and specific. In the most profoundly general sense, the very enactment of this legislation reflected and represented a monumental shift in the power relationships between museums and Native communities and their cultural patrimony. In that respect NAGPRA legislation is like the sharp point at the tip of an iceberg. But if you look at the original law and its implementation, there’s a lot that is undefined. After the experience of a generation, the new regulations fill in more specifics, including elevating and accenting more explicitly the authority that should be accorded evidentiary matter in repatriation questions to the perspective of Native people themselves.”

The two parts of the law, he continues, call for slightly different approaches to facts. With regard to return of human remains and funerary materials, “almost everyone agrees now that we must undo what was an incredible and terrible wrong.” For repatriation of cultural property claims, “the new regulations accent and make more specific the duties for formulating evidence with regard to applications that come out of the communities themselves. Relevant evidence is now not simply a matter of ‘science,’ but a matter of connections and ties that may be established within Native communities. The new regulations refer rather directly to the ascendance of that kind of evidence in considering how applications for repatriation are looked at, analyzed and adjudicated.”

Although NAGPRA has been an enforceable law since the 1990s, prominent institutions were seemingly taken by surprise when the new regulations were issued. This past January, the American Museum of Natural History in New York closed galleries dedicated to Eastern Woodlands and the Great Plains, and covered a number of cases displaying Native American cultural objects. The Field Museum of Chicago and the Cleveland Museum also covered cases, and the Peabody Museum at Harvard University decided to remove all funerary belongings from public view. Given that NAGPRA has been the law since the 1990s, why did these institutions respond so dramatically to the new regulations? West replies, “I want to speak gently about this. Maybe wisdom comes later in some places.”

Many tribes were critical of NAGPRA for empowering museums to make decisions about whether Indigenous people had valid connections to their ancestors. After ProPublica published investigations of NAGPRA compliance last year, Native activists expressed their discontent by dividing major museums holding Native American collections into categories of “good” (exemplified by the Brooklyn and Denver Museums) and “bad” (the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Harvard University’s museums). The famous Diker collection of Native American art at the Met was the subject of well-publicized scrutiny revealing that a majority of the 139 objects donated or loaned by the Dikers have incomplete ownership histories. Some lack any provenance at all.

Responding to critics of the Met’s presentation of the Diker collection, Patricia Marroquin Norby (Purépecha), the museum’s first curator of Native American art, published her own report on the collection and its Met museum background. “The Met is a 153-year-old historically colonial institution,” she noted. “Upon my arrival [in 2020] the museum did not have the infrastructure for caring for or presenting Native American and Indigenous art according to diverse Indigenous perspectives. This is not unique to the Met or the field.” With guidance from NAGPRA, “we strategized a regionally directed plan for updating collection summaries for submission to all Native American tribes materially represented in our collections. We reached out to hundreds of communities and held consultation visits.” The documentation and repatriation process, she emphasizes, is complex, time-consuming, and requiring of great care. As a result, “it is not surprising that much of the recent and highly publicized criticism originates with people who have never worked at a museum or have not worked at a museum long enough to see through policy, process, or other necessary institutional changes. Museum teams know first-hand that … reactive change is not sustainable, particularly when caring for museum collections, the public and each other.”

The Met and other museums with significant Native American collections are also being criticized for displaying work with descriptions that omit or minimize information about the wars, occupations, massacres, and exploitation that dominated the tribes’ past. West advocates that, as a matter of curatorial practice, “it is important to acknowledge the full spectrum of the viewer’s experience. You have to, in some way, contextualize the historical beginnings. None of that is very pleasant, but it’s part of the story. Art museums should think more about how it should be done.”

Looted Art: New Approaches

A precedent may be offered by a New York law passed in 2022 requiring museums to publicly identify objects in their collection displaced by Nazis during the Holocaust. The law states that works of art known to have changed hands by involuntary means in Europe during the Nazi era (1933–45) must be identified with “a placard or other signage acknowledging such information along with such display.” The American Association of Museum Directors and the American Alliance of Museums have established similar ethical principles for handling Nazi-looted art, but there is no enforcement mechanism. As O’Donnell observes, “it would seem that the threat of legal liability under this new amendment supports the notion that something more than best practice recommendations might be a good idea.”

From an historical perspective, the most familiar controversies about looted art involve Western European classical antiquities. Elizabeth Marlowe, a professor of art history at Colgate University and specialist in Roman Imperial art, is a prominent voice in reviews of museum practices in the collecting and repatriation of ancient art. “Museums still tell stories about their classical collections to fend off demands for repatriation, I’m sorry to report,” she says. “But the fact that shady antiquities dealers have been identified and prosecuted nationally and internationally has forced museums and collectors to grapple with the very real consequences for acquiring stolen or illegally exported works of art. No one wants the Manhattan District Attorney’s office to show up and ask to see their files.”

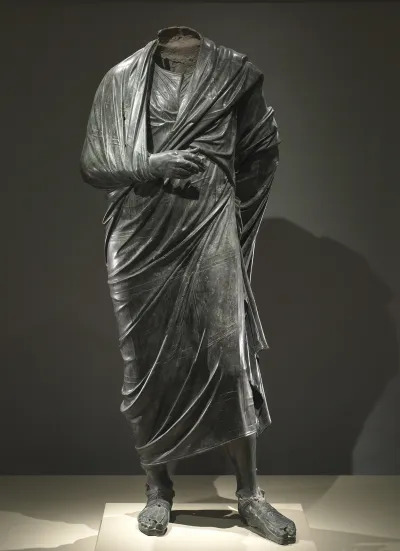

In Marlowe’s view, the most important legal case involving antiquities in the US now concerns a Roman statue from the CMA’s collection identified until recently as The Emperor as Philosopher, Probably Marcus Aurelius. As Marlowe outlined in a recently published article, acting on a tip about looting in 1967, Turkish officials discovered a magnificent bronze statue in a tiny village near the Roman site of Bubon. Archaeologists subsequently uncovered a platform at the site with statue bases inscribed with the names of 14 Roman emperors and empresses. The statues had all disappeared, save the one the Turkish authorities first discovered. Starting in the mid-1960s rare ancient bronze statues and Roman imperial portraits mysteriously appeared on the market. Several were purchased by New York collectors and acquired by museums, including the CMA. Last December the Manhattan Antiquities Trafficking Unit repatriated 41 looted ancient artworks to Turkey. Among them were eight bronzes from the Bubon site, including sculptures relinquished by the Met Museum; the Fordham Museum of Greek, Etruscan, and Roman Art; the Worchester Art Museum; and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Absent from the group was the most impressive sculpture associated with Bubon, the draped figure in the Cleveland Museum collection. Unlike the other museums presented with evidence that they housed work looted from the Bubon site, the CMA opted not to surrender its bronze, acquired in 1986 for the then astronomical price of $1.85 million. Instead, the museum has filed a lawsuit against the Manhattan District Attorney seeking a declaration that the museum is the rightful and lawful owner of a headless bronze whose likely illicit origins have been documented in a major scholarly journal. “Many museums are watching this case closely,” Marlowe reports. “Cleveland is playing a game of chicken with the DA’s office, arguing that the DA can’t prove the sculpture came from Bubon, even though we know it has to have been stolen from somewhere in Turkey. In the end it all comes down to a philosophical question: how much proof

is enough?”

It is significant that the DA’s evidence was sufficient to convince the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston to relinquish its artwork. Provenance issues there are the purview of MFA Boston senior curator of provenance Victoria Reed, who operates in all museum departments and is heralded by colleagues as a persuasive pragmatist and “damned good detective.” Reed points out that, during her 21-year tenure in Boston, she has worked to “resolve many ownership claims, repatriate works of art and reach financial resolutions to keep works of art in the collection. Only once have we gotten into litigation. I think we have been successful because we try to uphold the spirit of the law, not just the letter. The task evolves.

“Over the last few years, like many other museums, we have begun to think more broadly about what to do with works of art in our collection that were taken during periods of colonial occupation, stolen or given up under duress. These concerns are not limited to European colonialism, of course. We need to deal with works of art relinquished under the Nazi regime and the effects of stateless colonialism on Native Americans where consent for acquisitions was often not given. Parameters are shifting,” she adds, “and we have to think beyond an established legal framework to address many of these situations. Transparency in all cases is a great responsibility to uphold. There’s a new generation of curators coming along who are much more sensitive about what we display in the galleries than we were 10 or 20 years ago. They are thinking not just about how we got these objects, but where they came from originally and what responsibilities that might entail. Those questions may not have answers in strictly legal terms, but we can try to be guided by the rationale for enacting art laws in the first place.”

Working Artists Grapple with AI and Copyright

Lawyers who specialize in legal rulings affecting working artists point to other highlights. Last year’s decision by the US Supreme Court holding that the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts violated photographer Lynn Goldsmith’s copyright is ranked as in important development in fair use. Without her knowledge or permission, Vanity Fair decided to publish a Warhol silkscreen based on Goldsmith’s photograph and the Foundation collected a $10,000 licensing fee. According to the Foundation, the authorization fell under the purview of fair use. The Court disagreed. “If you are a photographer or graphic designer or another artist who relies on licensing fees in commercial contexts, this case can inhibit rip-offs of your work,” attorney Jeffrey Cunard explains. “The word is out.”

Cunard is a former partner, and now of counsel, at Debevoise & Plimpton, and a former longtime counsel to the College Art Association and other copyright owners and users, who also follows intersections of artificial intelligence and copyright law. The US Copyright Office and the courts regard authorship, for purposes of owning a copyright, as a human endeavor. Artists can use AI to create an original artwork protected by copyright, but the Copyright Office has taken the position that the law should preclude copyright protection for creations generated entirely by AI. The catch, according to Cunard, is the spectrum of possibilities: “If I tell AI to create a ‘beautiful work’ for me, and the result is a truly beautiful artwork, who is the author? There is a push out there to get AI tools named as authors, and the outcome is unpredictable.”

A version of this article appears in the 2024 ARTnews Top 200 Collectors issue.