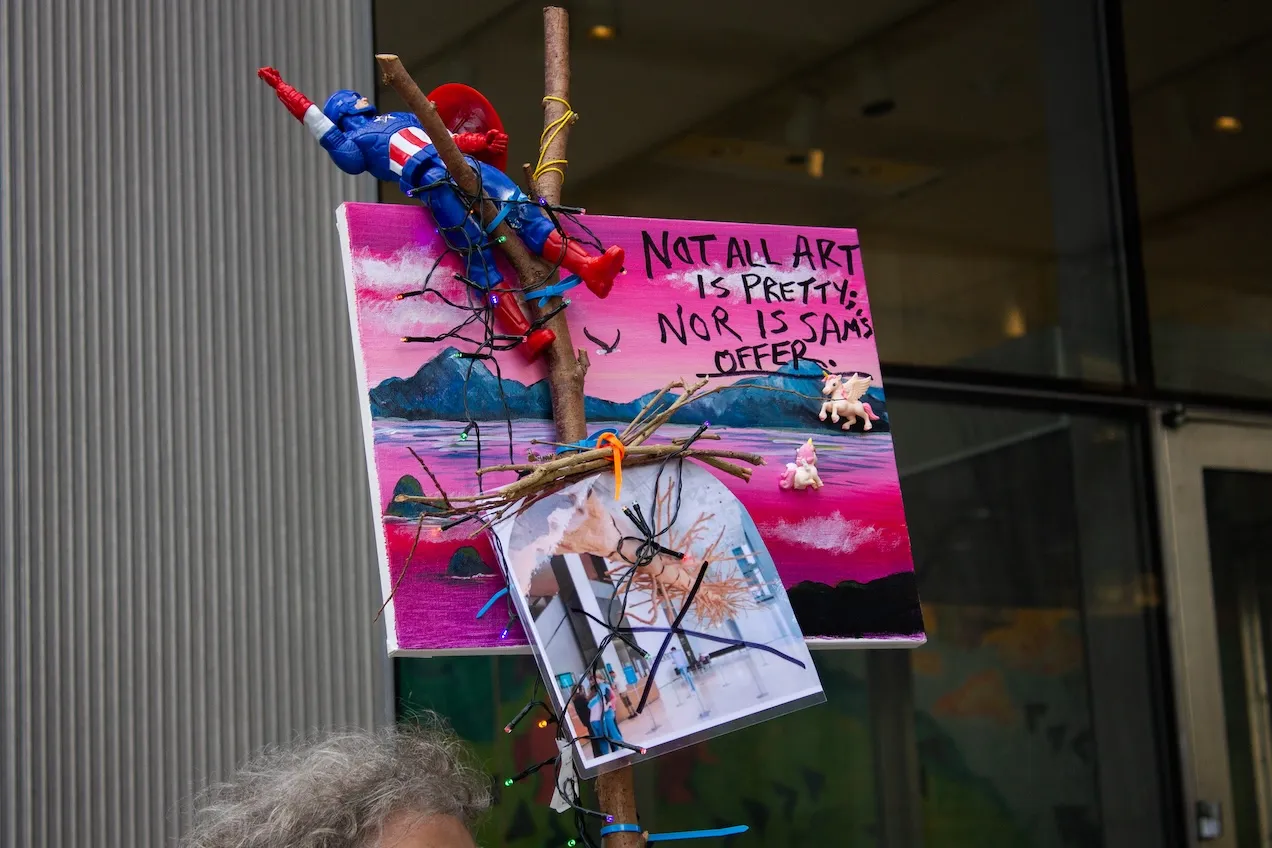

The Seattle Art Museum‘s union remains on strike one week after the workers began their stoppage. In a statement, the union claimed that the institution has been “bargaining in bad faith” during the negotiations over a contract.

The union, officially called SAM VSO (short for Visitors Services Officers), has asked for retirement benefits, a wage system based on seniority, and opportunities for career advancement.

ARTnews has contacted the Seattle Art Museum for comment.

The unionization effort at SAM went public in January 2022, though organizing began as early as May of 2021. More than two years later, the union and museum leadership are still at the bargaining table, making this one of the longest contract negotiations in recent museum history—nearly twice the national average, according to data from the nonprofit Museums Moving Forward.

The museum said in a December 4 statement that it had put forward the “last, best, and final offer to the union on October 31,” and that the deal is available until December 20. A week ago, the union, which represents around 70 percent of the museum’s internal security, began its strike.

SAM leadership is currently offering a new hourly wage of $23.25 an hour, slightly below the union’s latest offer of $24.75, which was already down from the group’s initial ask of $27.

“A full-time job should serve the basic things you need to take care of yourself, housing, food, health, even mental health,” Marcela Soto-Ramirez, a union co-representative who has been at the museum for three years, told ARTnews. “I’ve struggled to buy shoes, which I need as I spend all day in the galleries. Why should my coworkers and I have to go to Goodwill for shoes?”

In a statement released earlier this month, SAM described its wage offer as “market-leading rates.” But the proposed wages are still beneath what is by some estimates necessary to afford a living in Seattle. In 2023, the Seattle Times reported that the average Seattle renter needs to make $40.38 per hour, or $84,000 per year, to afford a one-bedroom apartment.

Workers also lost their 403(b)-retirement match during the Covid-19 pandemic; retirement benefits have been partially restored since the unionization started.

Included in the union’s demands is a contractual provision that would establish a union ship, also known as a union security clause. This would require employees in the department to belong to the union and pay dues.

“Without mandatory dues unions have to chase down its members like debt collectors,” said union representative Joshua Davis, a gallery guard who has worked at the museum for over a decade. “It’s like a hole in the boat that’s always letting in water, making it so that we don’t have the time for action planning and organizing—the things that have gotten us the wins we even have.”

One part of SAM VSO’s struggle is that its name is a bit of a misnomer. Outside of curatorial and executive positions, it’s increasingly common for museum employees to work across departments; a gallery guard one day may be working the gift shop, or the information desk the next, despite their official job title.

Nizan Shaked, a professor of art history and museum and curatorial studies at California State University Long Beach, told ARTnews that this is indicative of an industry-wide trend. “More and more in the last 20 years there has been a collapsing of the function of the guard and the function of the docent, and visitors to the museum know this,” she noted, adding, “A struggle between the VSO and the museum board, a labor-based struggle, only reveals the contradictions of an institution—this stated purpose of serving the field, and this knee-jerk reaction to union bust.”

According to Davis, after the union push began, some SAM employees were similarly reclassified to have the word “security” in their titles. When the union initially moved to be represented by International Union of Painters and Allied Trades (IUPAT) Local 116 rather than create an independent union, the group was met with immediate opposition.

Per a 1947 in clause the National Labor Relations Act, when one is classified as a “security worker,” one is legally only a security worker. “Guards”, at the time, was strictly defined as any individual employed in a position of enforcing rules that defended employer property or the safety of persons on the employer’s premises. The clause offers a distinction between those in security from the rest of staff, potentially preventing the creation of what’s called a wall-to-wall union, one that represents the entire staff—effectively blocking the union’s affiliation with a larger national union.

“Different unions have different strategies over which positions to fight for, and I think some have written off guards as such a difficult fight that they don’t even broach it,” Amanda Tobin Ripley, a co-developer of Museums Moving Forward’s Art Museum Unions Index, told ARTnews. “Museum workers, most of whom have no labor union experience, accept this advice without necessarily knowing that they can challenge this.”

With the board declining to recognize IUPAT as a representative of VSO, the union was left at an impasse. The National Labor Relations Board can’t represent the union because there of a clause that prohibits the NLRB from such certifications if a union represents security workers andnon-security workers.

In a statement issued in 2022, a SAM representative said that “voluntary recognition of this union would not address the conflict issues that the law is designed to prevent and that the union recognized by withdrawing its NLRB petition.”

This doesn’t mean such recognition is impossible in the museum sector, or more general workforce. Service Employees International Union, a “mixed guard” union like IUPAT Local 116 aimed to be, represents security personnel at Allied Universal, which contracts with Amazon. Museums that have successfully included guards in their units per voluntary recognition include the Walker Art Center, the Walters Art Museum, and the Tacoma Art Museum.

At the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, the Local 2110 union tried—unsuccessfully—to include visitor services staff who had been internally reclassified as hybrid security and visitor services workers. After museum pushback, the case went to arbitration; the NLRB ruled in favor of the museum.

“Guard and manager exclusion may be fairly typical,” Ripley said, adding that SAM pushing back over what counts as security was more unusual. “Every new art museum contract negotiated to date has included a union security clause, unless the museum is located in a right-to-work state, which only applies to the Milwaukee Art Museum so far.”

Other unionized museums, including the MFA Boston, Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Brooklyn Museum, already had unions for security personnel in place. However, the choices of parent union for security workers is limited. Often, the most viable option is aligning with unions that represent police—something SAM workers were unwilling to do.

“The majority of workers here are trained artists,” Davis said. “Some got into this to become curators. It’s a bizarre set-up that the museum’s stated mission is to be supporting artists, but they will not support their survival. My coworkers are going to the food bank.”