If you’ve heard of Marie Laurencin (1883–1956), it’s probably as that lone female artist in Picasso’s early circle who painted women in pastel blue and pink. What’s less known, though, is that Laurencin was subtly subversive as Cubism reigned supreme. “Why should I paint dead fish, onions, and beer glasses?” Laurencin said of her subject matter of choice. “Girls are so much prettier.”

Her reasons for painting women differed from those of her male peers, though. One could easily look at her canvases and see a saccharine world of woodland fairies wearing chiffon. Look closer, though, and you’ll find a female-dominated realm where men neither belong nor are welcome, the kind of realm preferred in the lesbian circles of 1920s Paris. “There is a darkness and a mystery and a surrealist aspect to her work that is not just candylike,” says Cindy Kang, curator at Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation and co-curator of the Laurencin solo exhibition there running through January 21, titled Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris. “Yes, it’s pink and blue and has flowy fabrics and all that,” Kang adds, “but there is a darkness there that is really speaking to these different worlds that she existed in.”

Part of Laurencin’s genius lay in painting works that appealed to her own lesbian community and to independent women like Gertrude Stein, Coco Chanel, and Helena Rubinstein, yet were coded enough to engage male collectors such as John Quinn (who acquired seven of her paintings) and Dr. Albert Barnes (who had at least four Laurencins).

A multimedia artist, Laurencin created paintings and prints, illustrated books, designed costumes and sets for ballet, and did collaborative decorative projects during her five-decade career. And it all began for her, the story goes, with a teacup.

-

Early life

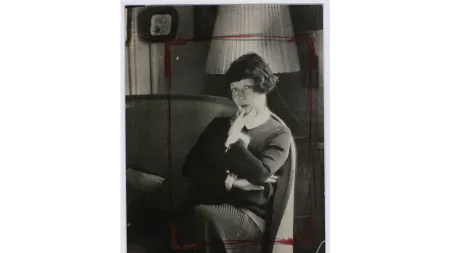

Image Credit: Musée Marie Laurencin, Tokyo. Artwork copyright © Fondation Foujita/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2023. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. Born in Paris, Laurencin was the illegitimate daughter of a seamstress, who raised her solo, and a father who sponsored an upper middle-class education for her. When Laurencin was a teenager, her mother asked her to paint a teacup, and her drawing skills showed enough promise for her to study art formally.

Laurencin started attending a municipal drawing school in Paris’s Batignolles neighborhood soon after, around 1902, and also studied porcelain painting. In 1904 she dropped the latter and enrolled at the Académie Humbert in Paris, where she met Georges Braque, Francis Picabia, and other artists. Through other academy students she met writer Henri-Pierre Roché, who became one of her closest friends and fiercest supporters.

One of Laurencin’s earliest works was a 1905 print titled Song of Bilitis, named after Pierre Louys’s 1894 erotic text portraying Sapphic love and supposedly written by a peasant girl who went to Lesbos and entered poet Sappho’s circle. Laurencin’s print shows two embracing women about to kiss. Sappho had reentered French modernism through works by Baudelaire and others, and though men were the intended audience, the print was also relatable to queer women, with the story’s classicism nestling it within conventional tradition.

An early Laurencin painting was Self-Portrait (1905), a subject she returned to throughout her career. By spring 1907 she had met Picasso, who took an interest in her work and introduced her to Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet who chronicled Cubism. From then on Laurencin was an important member of the “bande à Picasso.”

-

Art student and semi-Cubist

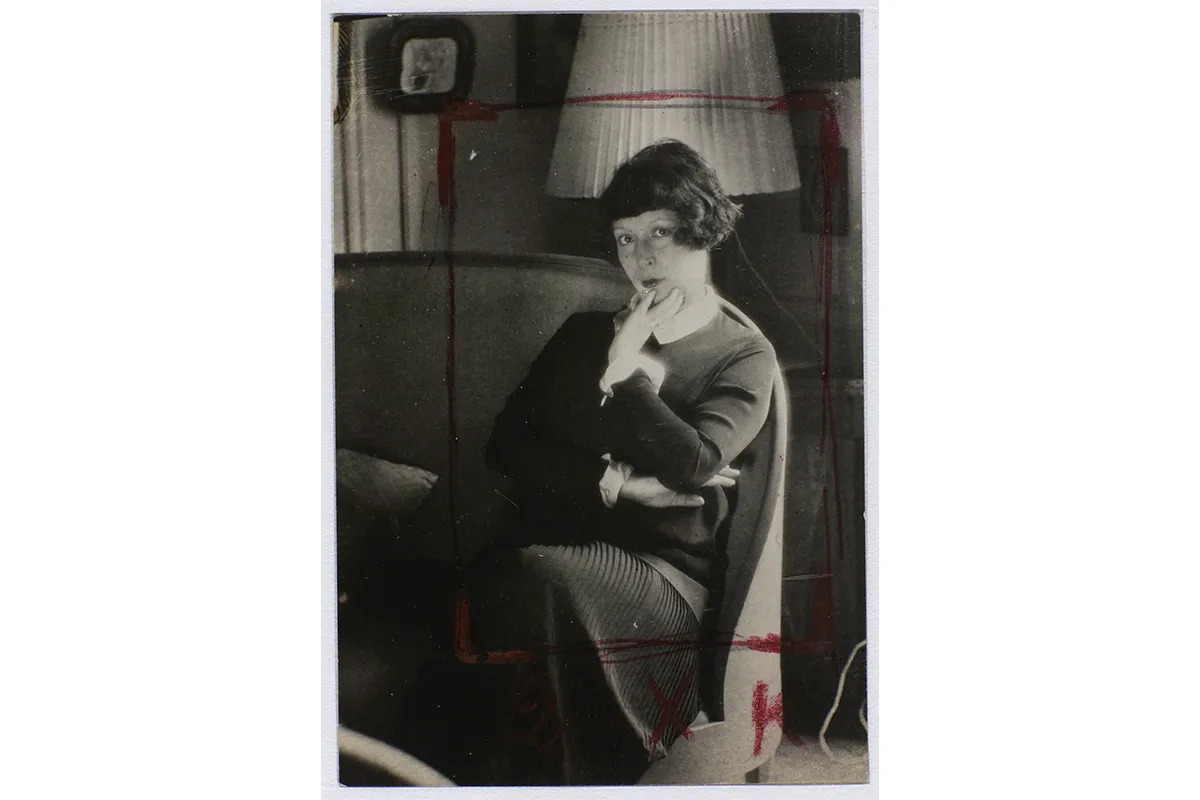

Image Credit: Private collection, Germany. Artwork © copyright Fondation Foujita/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2023. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. Laurencin and Apollinaire were romantically involved from 1907 until 1913, and he appears in some of her group portraits from this period. A 1908 painting titled Group of Artists (Groupe d’artistes) shows her alongside Apollinaire, Picasso, and the latter’s then companion Fernande Olivier; in the work, a prominent Laurencin is slightly bigger than her friends.

A year later, in another group portrait titled Apollinaire and His Friends (Apollinaire et ses amis) (1909) with Apollinaire, Gertrude Stein, Olivier, Picasso, and poets Marguerite Gillot and Maurice Cremnitz, Laurencin still dominates, this time in the right foreground. (Apollinaire kept this painting after his relationship with Laurencin fizzled, hanging it above his bed for the rest of his life.)

Laurencin experimented with Cubism, but on her own terms. “She wasn’t really trying to do what Picasso and Braque were doing,” says Kang. “She was very interested in their research, their theories, and she took little bits from what they were doing to incorporate into her own work, but she didn’t fully drink the Kool-Aid.” In works such as Young Women (Les jeunes filles) (1910), for example, Laurencin painted four women in her emerging signature style, but with Cubist-looking houses in the background.

Picasso admired Laurencin’s work and acquired her painting The Dreamer (La songeuse)(1910–11), also recommending her to artist Walt Kuhn in a list of 10 artists he felt should be included in the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show in New York (where she would exhibit seven works).

Ultimately, though, Laurencin felt that her ties to the Cubists kept her back. Her break with Apollinaire and the beginning of World War I led to a marked separation from the group, and it was during this time that she developed her distinct style. “Cubism has poisoned three years of my life, preventing me from doing any work. I never understood it,” Laurencin said in a 1923 interview with the art critic Gabrièlle Buffet-Picabia. “As long as I was influenced by the great men surrounding me, I could do nothing.”

-

Spanish exile and a shift in style

Image Credit: Centre Pompidou–Musée National d’Art Modern/Centre de Création Industrielle, Paris. Artwork copyright © Fondation Foujita/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2023. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. In 1913 Laurencin not only ended her relationship with Apollinaire but also lost her mother, whom she was close to and lived with. These events may have pushed her to marry German aristocrat Baron Otto von Wätjen in June 1914 after a short courtship. The newlyweds were honeymooning in southern France when World War I broke out and Watjen, as a German citizen, couldn’t return to Paris. Since he didn’t want to go to Germany, they waited out the war in Madrid, where he spent much of his time carousing (without his new wife).

Laurencin’s isolation in Spain may have contributed to the development of her mature style. Her prewar canvases are painted thinly with some areas bare, while her postwar works feature thick layers of white. She also pared down her color palette to pink, blue, and gray with occasional greens and yellows.

“I am getting on better in Spain and if I go to the Prado in Madrid it is impossible, despite all that is going on, to forget that I am a painter,” Laurencin wrote in October 1914 to French gallerist Paul Rosenberg, who had begun representing her in 1913. “The Goyas, the El Grecos, and even the Velázquezes are closer to our mentality than the boring Mona Lisa.” Goya was a major influence on Laurencin, and she especially looked to his paintings of women.

Laurencin had begun a series before leaving Paris, called Two Friends (Deux amies)—an ambiguous title that could also refer to lovers. Her canvas Women with a Dove (Femmes à la colombe) (1919), for example, is seemingly of fond friends but is actually a painting of Laurencin and her lover, fashion designer Nicole Groult. Groult and Laurencin are here depicted as what might be read now as a same-sex couple; at the time the work was well received and auctioned publicly in 1924 at the Parisian Hôtel Drouot, where it sold to art dealer Lord Joseph Duveen (who gifted it to the French state in 1931).

These female-dominated paintings rendered in an overtly feminine palette and manner were a deliberate part of Laurencin’s style and an expression of her self-image. “One of the things about Laurencin is that she stayed really under the radar” in terms of her queer identity in her work, Kang observes. “When you begin to see it, it’s there and you’re, like, ‘Oh, of course.’ But you could very easily miss it. It’s very subtle, it’s coded, it’s meant to appeal to many different kinds of audiences,” Kang continues. “It is a camouflage. And that’s the clue: the over-the-top femininity.” In this regard, her work was quite different from that of Tamara de Lempicka, another artist active in Parisian lesbian circles at the time, whose erotic paintings of women were more obvious than Laurencin’s.

Laurencin’s marriage to Wätjen deteriorated toward the end of their stay in Spain, and when she returned to Paris in 1920 she was a newly free woman.

-

Laurencin and the lesbian avant-garde

Image Credit: Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris. Artwork copyright © Fondation Foujita/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2023. Image copyright © RMN-Grand Palais /Art Resource, New York. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. Laurencin’s big reentry on the Parisian scene was a large exhibition of 25 paintings in March 1921 at the Galerie Paul Rosenberg. Though Rosenberg had represented her for years, this was her first solo presentation at his gallery, and it bolstered her reputation (including among foreign collectors, some of whom bought her work following the show). Until then, Laurencin had been thought to owe her exhibition opportunities to her relationships with Apollinaire, Braque, and Picasso, but this show presented her on her own, and it revamped her image.

Laurencin instantly became one of the most successful female artists in Paris, a position she held until the onset of World War II. Beyond gaining her a new clientele and greater esteem, the show led to new collaborations, such as with the Ballets Russes, for which she helped create the stage curtain and set decor for Les Biches, which premiered in 1924. Laurencin also received portrait commissions from women including Baroness Eva Gebhard-Gourgaud.

Laurencin painted scenes from classical and familiar stories in ways open to interpretation. A work like The Amazon (1923), for example, which was acquired by publisher and collector Scofield Thayer, could be received as an easily digestible feminine image with a classicizing title. To the women in Laurencin’s circle, though, an Amazon was a queer archetype.

In another painting, Judith (1930), Laurencin depicted an alternate version of the biblical story of Judith, the woman who killed the Assyrian general Holofernes. Here, Holofernes is completely absent; Judith and her maidservant are depicted at the moment when God blesses Judith as she prepares to enchant (and then behead) the general. Meanwhile, the maidservant is openly admiring Judith’s beauty and especially her exposed breast (perhaps an autobiographical reference, since in 1925 Laurencin hired a maid named Suzanne Moreau who became her lover and life partner).

By the 1930s, with Laurencin settled into a commercially successful style, her work became repetitive, but she was still acknowledged as significant within French art. In 1935 she was awarded the Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, and two years later the French state acquired her painting of five women in an idyllic setting, The Rehearsal (Le répétition)(1936). She wrote and published a memoir, The Night Diary (Le carnet des nuits) (1942), in which she alluded to her queerness.

-

Laurencin’s work reevaluated

Image Credit: Private collection, Stowe, Vermont. Artwork copyright © Fondation Foujita/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris 2023. Courtesy Barnes Foundation. Women have always digested Laurencin differently from men. “To please men, it’s better to pass for stupid,” Laurencin once said according to an account written in 1926 by lesbian bookseller Adrienne Monnier. “Myself, I am the queen of airheads [la reine des gourdes].” Laurencin sometimes “played dumb,” possibly as a commercial tactic, but in reality she was anything but, amassing a library of around 5,000 books over her lifetime.

“To be an ambitious woman in a world where men held positions of power, Laurencin devised a camouflaged intelligence. And it worked,” writes Rachel Silveri, assistant professor of art history at the University of Florida, Gainesville, in the exhibition catalogue for the Barnes Foundation’s Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris. “Without inheritance, without the financial support of a husband, and without supplementary income from another job, Laurencin earned her living by her artistic practice alone. Camouflaged intelligence became a tool in this endeavor—and an important one in a culture where queerness was ‘deviant, medically degenerate, and in some contexts, legally criminal.’”

Laurencin painted around 2,000 canvases in her lifetime. Since her death, “feminist art historians have been pretty divided on her work,” Kang says. Some of Laurencin’s own statements played into female stereotypes, and some “interpreted this as a subversive tactic.” But for others, “it feels like a capitulation to the patriarchy to play the dumb woman.”

Despite these conflicting attitudes toward Laurencin, she’s seen renewed attention over the past several years, partly because of a reevaluation of her work, and partly because of interest in her queer identity. Museums that kept her work in storage or back rooms for a long time are now looking at the paintings anew, and in addition to the Barnes Foundation solo exhibition of roughly 50 artworks, she’s had two other institutional shows over the past decade at the Marmottan Monet Museum in Paris and Seoul’s Hangaram Museum.

“There’s been a shift in the way that one sees her now,” says Simonetta Fraquelli, co-curator of the Barnes show, referring to the type of modernist Barbieland Laurencin conjured in her canvases. “These images of women and this world that she created, this alternative female world, is actually much more appealing than it was a few decades ago.”

Early life

Born in Paris, Laurencin was the illegitimate daughter of a seamstress, who raised her solo, and a father who sponsored an upper middle-class education for her. When Laurencin was a teenager, her mother asked her to paint a teacup, and her drawing skills showed enough promise for her to study art formally.

Laurencin started attending a municipal drawing school in Paris’s Batignolles neighborhood soon after, around 1902, and also studied porcelain painting. In 1904 she dropped the latter and enrolled at the Académie Humbert in Paris, where she met Georges Braque, Francis Picabia, and other artists. Through other academy students she met writer Henri-Pierre Roché, who became one of her closest friends and fiercest supporters.

One of Laurencin’s earliest works was a 1905 print titled Song of Bilitis, named after Pierre Louys’s 1894 erotic text portraying Sapphic love and supposedly written by a peasant girl who went to Lesbos and entered poet Sappho’s circle. Laurencin’s print shows two embracing women about to kiss. Sappho had reentered French modernism through works by Baudelaire and others, and though men were the intended audience, the print was also relatable to queer women, with the story’s classicism nestling it within conventional tradition.

An early Laurencin painting was Self-Portrait (1905), a subject she returned to throughout her career. By spring 1907 she had met Picasso, who took an interest in her work and introduced her to Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet who chronicled Cubism. From then on Laurencin was an important member of the “bande à Picasso.”

Art student and semi-Cubist

Laurencin and Apollinaire were romantically involved from 1907 until 1913, and he appears in some of her group portraits from this period. A 1908 painting titled Group of Artists (Groupe d’artistes) shows her alongside Apollinaire, Picasso, and the latter’s then companion Fernande Olivier; in the work, a prominent Laurencin is slightly bigger than her friends.

A year later, in another group portrait titled Apollinaire and His Friends (Apollinaire et ses amis) (1909) with Apollinaire, Gertrude Stein, Olivier, Picasso, and poets Marguerite Gillot and Maurice Cremnitz, Laurencin still dominates, this time in the right foreground. (Apollinaire kept this painting after his relationship with Laurencin fizzled, hanging it above his bed for the rest of his life.)

Laurencin experimented with Cubism, but on her own terms. “She wasn’t really trying to do what Picasso and Braque were doing,” says Kang. “She was very interested in their research, their theories, and she took little bits from what they were doing to incorporate into her own work, but she didn’t fully drink the Kool-Aid.” In works such as Young Women (Les jeunes filles) (1910), for example, Laurencin painted four women in her emerging signature style, but with Cubist-looking houses in the background.

Picasso admired Laurencin’s work and acquired her painting The Dreamer (La songeuse)(1910–11), also recommending her to artist Walt Kuhn in a list of 10 artists he felt should be included in the groundbreaking 1913 Armory Show in New York (where she would exhibit seven works).

Ultimately, though, Laurencin felt that her ties to the Cubists kept her back. Her break with Apollinaire and the beginning of World War I led to a marked separation from the group, and it was during this time that she developed her distinct style. “Cubism has poisoned three years of my life, preventing me from doing any work. I never understood it,” Laurencin said in a 1923 interview with the art critic Gabrièlle Buffet-Picabia. “As long as I was influenced by the great men surrounding me, I could do nothing.”

Spanish exile and a shift in style

In 1913 Laurencin not only ended her relationship with Apollinaire but also lost her mother, whom she was close to and lived with. These events may have pushed her to marry German aristocrat Baron Otto von Wätjen in June 1914 after a short courtship. The newlyweds were honeymooning in southern France when World War I broke out and Watjen, as a German citizen, couldn’t return to Paris. Since he didn’t want to go to Germany, they waited out the war in Madrid, where he spent much of his time carousing (without his new wife).

Laurencin’s isolation in Spain may have contributed to the development of her mature style. Her prewar canvases are painted thinly with some areas bare, while her postwar works feature thick layers of white. She also pared down her color palette to pink, blue, and gray with occasional greens and yellows.

“I am getting on better in Spain and if I go to the Prado in Madrid it is impossible, despite all that is going on, to forget that I am a painter,” Laurencin wrote in October 1914 to French gallerist Paul Rosenberg, who had begun representing her in 1913. “The Goyas, the El Grecos, and even the Velázquezes are closer to our mentality than the boring Mona Lisa.” Goya was a major influence on Laurencin, and she especially looked to his paintings of women.

Laurencin had begun a series before leaving Paris, called Two Friends (Deux amies)—an ambiguous title that could also refer to lovers. Her canvas Women with a Dove (Femmes à la colombe) (1919), for example, is seemingly of fond friends but is actually a painting of Laurencin and her lover, fashion designer Nicole Groult. Groult and Laurencin are here depicted as what might be read now as a same-sex couple; at the time the work was well received and auctioned publicly in 1924 at the Parisian Hôtel Drouot, where it sold to art dealer Lord Joseph Duveen (who gifted it to the French state in 1931).

These female-dominated paintings rendered in an overtly feminine palette and manner were a deliberate part of Laurencin’s style and an expression of her self-image. “One of the things about Laurencin is that she stayed really under the radar” in terms of her queer identity in her work, Kang observes. “When you begin to see it, it’s there and you’re, like, ‘Oh, of course.’ But you could very easily miss it. It’s very subtle, it’s coded, it’s meant to appeal to many different kinds of audiences,” Kang continues. “It is a camouflage. And that’s the clue: the over-the-top femininity.” In this regard, her work was quite different from that of Tamara de Lempicka, another artist active in Parisian lesbian circles at the time, whose erotic paintings of women were more obvious than Laurencin’s.

Laurencin’s marriage to Wätjen deteriorated toward the end of their stay in Spain, and when she returned to Paris in 1920 she was a newly free woman.

Laurencin and the lesbian avant-garde

Laurencin’s big reentry on the Parisian scene was a large exhibition of 25 paintings in March 1921 at the Galerie Paul Rosenberg. Though Rosenberg had represented her for years, this was her first solo presentation at his gallery, and it bolstered her reputation (including among foreign collectors, some of whom bought her work following the show). Until then, Laurencin had been thought to owe her exhibition opportunities to her relationships with Apollinaire, Braque, and Picasso, but this show presented her on her own, and it revamped her image.

Laurencin instantly became one of the most successful female artists in Paris, a position she held until the onset of World War II. Beyond gaining her a new clientele and greater esteem, the show led to new collaborations, such as with the Ballets Russes, for which she helped create the stage curtain and set decor for Les Biches, which premiered in 1924. Laurencin also received portrait commissions from women including Baroness Eva Gebhard-Gourgaud.

Laurencin painted scenes from classical and familiar stories in ways open to interpretation. A work like The Amazon (1923), for example, which was acquired by publisher and collector Scofield Thayer, could be received as an easily digestible feminine image with a classicizing title. To the women in Laurencin’s circle, though, an Amazon was a queer archetype.

In another painting, Judith (1930), Laurencin depicted an alternate version of the biblical story of Judith, the woman who killed the Assyrian general Holofernes. Here, Holofernes is completely absent; Judith and her maidservant are depicted at the moment when God blesses Judith as she prepares to enchant (and then behead) the general. Meanwhile, the maidservant is openly admiring Judith’s beauty and especially her exposed breast (perhaps an autobiographical reference, since in 1925 Laurencin hired a maid named Suzanne Moreau who became her lover and life partner).

By the 1930s, with Laurencin settled into a commercially successful style, her work became repetitive, but she was still acknowledged as significant within French art. In 1935 she was awarded the Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur, and two years later the French state acquired her painting of five women in an idyllic setting, The Rehearsal (Le répétition)(1936). She wrote and published a memoir, The Night Diary (Le carnet des nuits) (1942), in which she alluded to her queerness.

Laurencin’s work reevaluated

Women have always digested Laurencin differently from men. “To please men, it’s better to pass for stupid,” Laurencin once said according to an account written in 1926 by lesbian bookseller Adrienne Monnier. “Myself, I am the queen of airheads [la reine des gourdes].” Laurencin sometimes “played dumb,” possibly as a commercial tactic, but in reality she was anything but, amassing a library of around 5,000 books over her lifetime.

“To be an ambitious woman in a world where men held positions of power, Laurencin devised a camouflaged intelligence. And it worked,” writes Rachel Silveri, assistant professor of art history at the University of Florida, Gainesville, in the exhibition catalogue for the Barnes Foundation’s Marie Laurencin: Sapphic Paris. “Without inheritance, without the financial support of a husband, and without supplementary income from another job, Laurencin earned her living by her artistic practice alone. Camouflaged intelligence became a tool in this endeavor—and an important one in a culture where queerness was ‘deviant, medically degenerate, and in some contexts, legally criminal.’”

Laurencin painted around 2,000 canvases in her lifetime. Since her death, “feminist art historians have been pretty divided on her work,” Kang says. Some of Laurencin’s own statements played into female stereotypes, and some “interpreted this as a subversive tactic.” But for others, “it feels like a capitulation to the patriarchy to play the dumb woman.”

Despite these conflicting attitudes toward Laurencin, she’s seen renewed attention over the past several years, partly because of a reevaluation of her work, and partly because of interest in her queer identity. Museums that kept her work in storage or back rooms for a long time are now looking at the paintings anew, and in addition to the Barnes Foundation solo exhibition of roughly 50 artworks, she’s had two other institutional shows over the past decade at the Marmottan Monet Museum in Paris and Seoul’s Hangaram Museum.

“There’s been a shift in the way that one sees her now,” says Simonetta Fraquelli, co-curator of the Barnes show, referring to the type of modernist Barbieland Laurencin conjured in her canvases. “These images of women and this world that she created, this alternative female world, is actually much more appealing than it was a few decades ago.”

Boat of the Week: The World’s Fastest Yacht Can Transforms Into a Floating Dance Club at Night

Natura & Co. to Delist From the New York Stock Exchange

Vision Pro guided tour: Apple offers deep dive into its first spatial computer

Action Network CEO Patrick Keane Departing Company