For around a century, Gustave Caillebotte was the most discreet of the Impressionists, only coming back into the spotlight in 1994, when the Grand Palais in Paris celebrated the centenary of his death in 1894 through a memorable retrospective. Ever since, the French painter has been the subject of several exhibitions from London to Washington, D.C. to Switzerland.

Now, the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and the Art Institute of Chicago have joined forces to examine Caillebotte anew, with a sweeping retrospective “Painting Men,” which runs through January in Paris, before heading to LA next spring and then Chicago next summer. Despite the acclaim the artist has received over the past three decades, he still remains a bit of a mystery, a major focus of the exhibition which also coincides with the 130th anniversary of the artist’s passing.

“When facing this attractive, modern, yet enigmatic man—we still don’t know who he is—I realized we had good starting point,” Orsay curator Paul Perrin, who organized the exhibition with Scott Allan of the Getty and Gloria Groom of the Art Institute, told ARTnews in an interview. That starting point is Caillebotte’s singular focus on the male figure, the only of the Impressionists to consistently turn his gaze to masculine musculatures and the all-male spaces of the bourgeoisie: awe-inspiring soldiers that he spotted while in the military, family members, smartly clad passers-by, bare-chested workers, oarsmen, and more fill his tableaux. (Out of the 76 works shown by the artist between 1876 and 1888, 33 depict men versus 16 women.)

In the early 1870s, Caillebotte, who came from an aristocratic family who maintained themselves as rentiers (landlords), quit law school to train with Léon Bonnat, a leading artist and professor who trained a generation of artists in the French academic traditions, and later entered the École des Beaux-Arts. Turned down by the jury of the 1875 Salon, Caillebotte joined the Impressionist group, eager to turn his back on academic painting and to explore the day-to-day life of his contemporaries and Parisian living. Caillebotte’s relationship with his two brothers (Martial, who enjoyed music and sailing, and René, who died at only 25 years old) inspired him to always look for a sense of fraternity around him, namely among his fellow Impressionists, and within the communities he planned to depict.

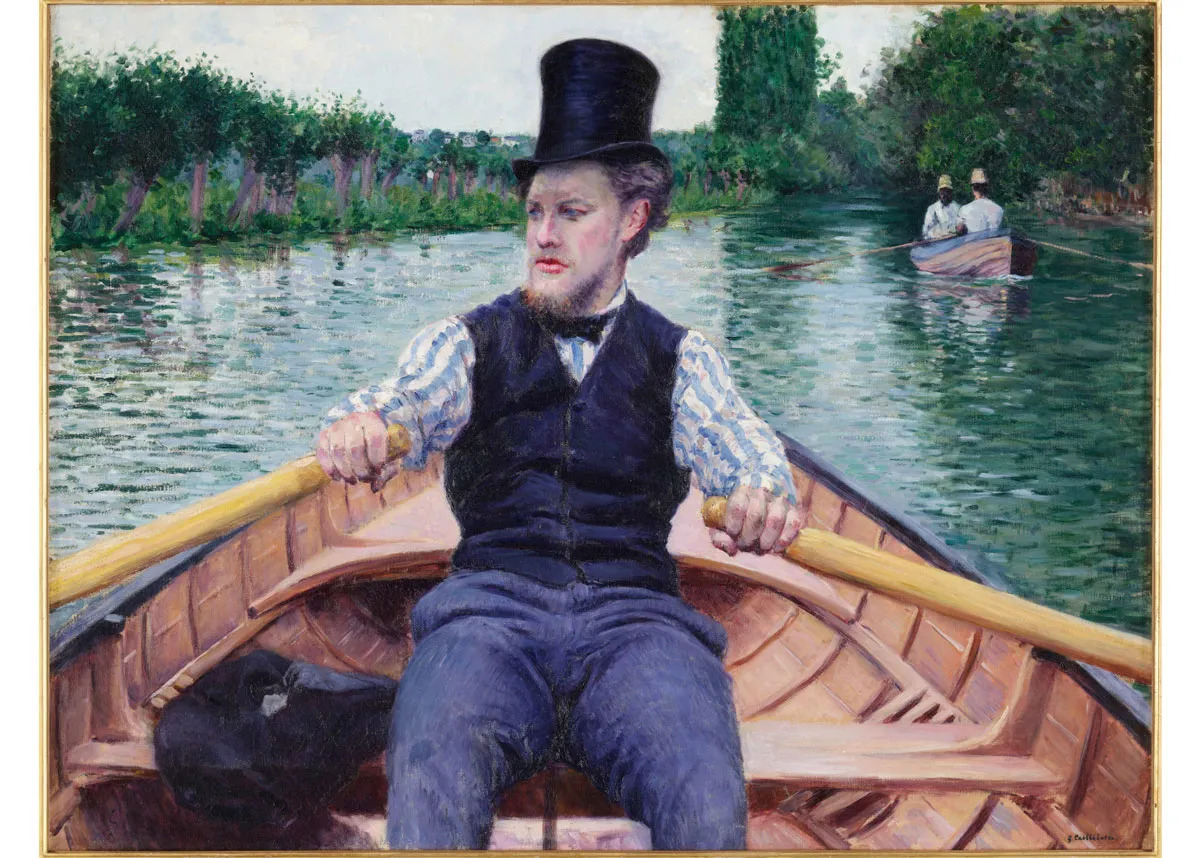

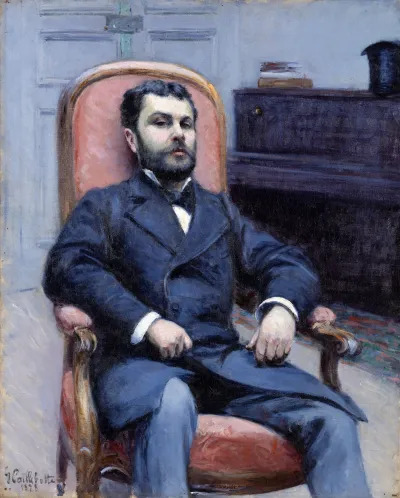

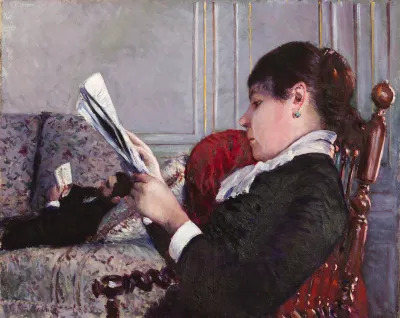

Caillebotte’s relatives and friends and others in his orbit feature in a majority of his paintings, but some of his sitters still remain unknown, like the sitter for Partie de bateau (1878). “That was the question that guided some of our research,” said Perrin. “In light of new documents, we managed to identify 15 of them, or rectify assumptions that had been made about [who they were].” Among these positive identifications is Richard Gallo, who features in Interieur, femme lisant (1880), showing him reclining as he reads, and Portrait de M. Gallo (1881), in which he sits, arms crossed, on a boldly patterned, orange and green striped sofa. For decades, Gallo was thought to be a journalist, but there is no record of him publishing anything. New research for this exhibition revealed Gallo to be, in fact, the son of a banker, who also studied law and lived as a rentier like Caillebotte.

Then there’s Monsieur R., who, because of his initials and friendship with Caillebotte has historically been suspected to be businessman Antoine Patrice Reyre, who is believed to have met the artist either at the 1876 Impressionist exhibition or socially at the Hôtel Drouot.He is the model for Portrait de Monsieur R. (1877), a painting which also features in the background of Portrait de Madame X (1878), or Reyre’s mother. The blue-and-white couch on which Reyre sits is listed in Mrs. Martial Caillebotte’s posthumous inventory, which means Caillebotte likely painted his friend in the family home.

And while Perrin still can’t say for sure who the model for Partie de bateau is, he ventured a hypothesis: “I believe this gentleman could be painter Norbert Goeneutte who appears in [Renoir’s] Bal du moulin de la Galette, but Renoir is famous for taking some liberties with his models’ looks,” he said. (Caillebotte purchased Bal du moulin in 1879 and donated it to the French State upon his death; that work and some 70 others from his esteemed collection, by artists like Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, and Claude Monet, have been organized into a special presentation in an upstairs gallery at the Orsay for the run of the exhibition. The museum has also just now thoroughly inventoried that donation in a newly published catalog.)

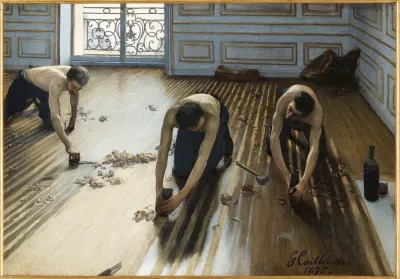

Some of Caillebotte’s subjects, however, will likely never have their identities uncovered, though they still were important parts of the artist’s life. “He does not paint just anyone, but people who work for him, or enjoy sailing like him,” added Perrin. The muscly laborers in Floor Scrapers, the Caillebotte painting that was likely rejected from the 1875 Salon but drew attention at the 1876 Impressionist exhibition, were actually employees of the Caillebotte family, preparing the ground for the artist’s future studio in the fashionable 8th arrondissement, home to luxury boutiques, as well as cultural and political institutions. The masterpiece hangs alongside drawings, a painted study, and a rarely seen version with two workers (versus three) painted from the side.

These works like several throughout the exhibition are on loan from private collections, which are paired with his famed masterpieces now held by museums. The revealing Self-Portrait with Easel (1879) is not far from the Art Institute’s Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877). The exhibition’s Paris iteration will be the only one to feature his pastels, which are too fragile to travel, while the LA and Chicago stops will include Young Man Playing the Piano (1876), from Tokyo’s Artizon Museum, as it was not available for the Paris show.

Elsewhere are Caillebotte’s scenes of gardeners watering his vegetable garden or a house painter dangling from a ladder as he applies a fresh coat to the façade of a wine shop. Several canvases show a bird’s-eye view of Paris’s crowded Haussmann-era boulevards, composed from his balcony. The human figure in Caillebotte’s hands as a whole appears to be a gateway to the artist’s privacy.

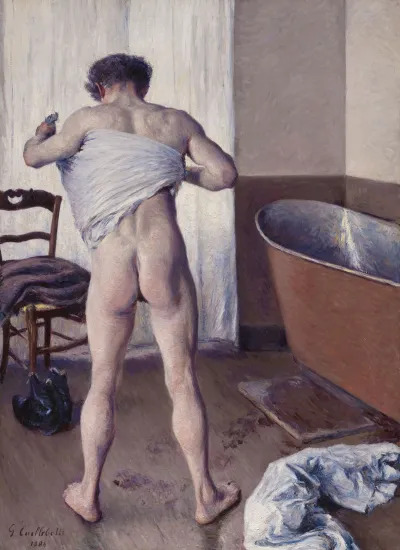

Offering a chronological and thematical overview of Caillebotte’s career that has something for longtime fans and new devotees of the artist, “Painting Men” reaches a climax in the section devoted to the very few nudes that Caillebotte produced in the early 1880s, just before landscapes and leisurely activities started taking over his attention. Nude on a Couch (ca. 1880), the only female nude ever painted by Caillebotte, was never exhibited in his lifetime, which the curators argue hints at his total lack of interest in women. (His contemporaries, by contrast, painted several female nudes.) Some scholars may object to that claim, given the nature of his relationship with Charlotte Berthier, whom he lived with out of wedlock though what they meant to each other remains a mystery. What kind of companion was she to him? We may never know.

His most famous nude, Man at His Bath (1884),was included in an exhibition by the avant-garde group Les XX, though kept in a back room. This work, showing a man from behind as he towels off, was likely too subversive for late 19th-century Parisians. But Perrin is quick to point out that “it’s not because one paints a handsome man that one necessarily feels desire for him.”

Some critics still wonder whether Caillebotte might have been gay or bisexual, and many have interpreted his work as a reflection of his suppressed homosexuality which, because he did not embrace it, caused him to slowly shift his practice to landscape. In examining this aspect of Caillebotte’s biography, Perrin wants to give visitors all the facts. The exhibition raises the question without giving a firm answer. “It’s not taboo, so we had to bring it up, but we still have no idea,” Perrin said. “The most admirable [thing] about Caillebotte is that he created strong, new images which escaped the conventions of his time.”

The modernity of Caillebotte’s painting resides in his debunking gender and social stereotypes. He borrowed the toilette subject from Edgar Degas, whom he admired greatly, but Caillebotte substituted in most cases Degas’s undressed women for unclothed male models. Interieur, femme lisant, on the other hand, shows Berthier, a woman of low extraction, in the foreground, and Gallo, the banker’s son, in the back. She is reading the newspaper, like a respectable man would; he is lying on a couch reading a book, like a young lady would. In inverting their roles, Caillebotte conveys a form of gender fluidity. “His painting are meant to be enigmatic,” Perrin said, “to try to read too much into it is missing the point.”

Paulina Pobocha Joins AIC as Chair and Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

In a Revelatory Georgia O’Keeffe Exhibition, Paintings of New York Unlock an Entire Oeuvre’s Mysteries

Inside the New Regent Santa Monica Beach, the Area’s Most Glamorous Hotel

What Estée Lauder’s Recent Exec Moves Mean for Stéphane de La Faverie, Fabrizio Freda and William Lauder’s Pay Packages

5 useful Apple CarPlay features you might have missed

NWSL 2024 Attendance Hits Record 2 Million Fans