Between 2010 and 2012, artist Violette Bule held a series of free photography workshops in penitentiaries in her home country of Venezuela. Over 3,000 images were created by the workshops’ incarcerated participants. That archive remained out of public view for over a decade, until Bule and art historian Michel Otayek last year published the photobook de la LLECA al COHUE, which features a selection of the images.

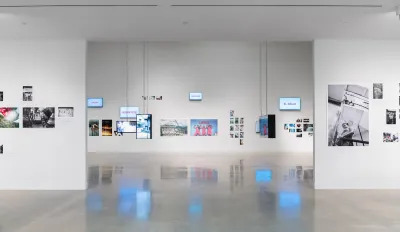

This fall, Bule and Otayek have collaborated again on the exhibition, “Una Luz: Photography Under Confinement in Venezuela, a collaboration,” at the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Open until December 7, the exhibition Luz expands upon Bule and Otayek’s book, bringing together hundreds of photos from the archive with audio, video, and text to highlight the power of collaboration and explore the power dynamics of working with marginalized communities.

The timing of the exhibition has coincided with a political crisis in Venezuela following the contentious reelection of President Nicolas Maduro in July. The disputed results sparked mass protests, which led to the arrest of nearly 2,000 protestors, including dozens of children.

“It is a tragic coincidence that our exhibition is on view at a moment of unprecedented political repression in our home country,” Bule told ARTnews in a recent interview. Otayek added, “While we never wanted to politicize this project, we must take a stand and denounce the weaponization of the criminal justice system to suppress dissent in Venezuela.”

Both collaborators hope that Una Luz can contribute to an open dialogue about democracy and social justice based on the recognition of the human dignity of incarcerated people.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

ARTnews: Can you talk about the concept of the exhibition? How does “Una Luz” differ from your 2023 photobook de la LLECA al COHUE? How did the book project eventually expand into the exhibition?

Michel Otayek: There are two ways to think about the exhibition’s title, “Una Luz.” One is the direct translation from Spanish. The other is the meaning of this phrase in Venezuelan prison slang. In standard Spanish, “una luz” means “a light.” These words carry a different meaning for incarcerated people in Venezuela, but we did not want to disclose the coded meaning of any expression borrowed from Venezuelan prison slang present in the exhibition. Our intention was to convey a sense of defamiliarization about language and prompt the viewer to consider the meaning of those words as a range of possibilities. The idea of light, which is intimately related to photography, points to different directions that relate to the spirit of the exhibition: freedom, hope, looking up or ahead, longing for someplace else. As with our book de la LLECA al COHUE, this exhibition does not have a documentary purpose. The images do not present a visual summary of the reality of Venezuelan prisons. This project focuses instead on the value of creative expression for women and men living under confinement.

Violette Bule: There is another sense of the word “light” that is important for us. The exhibition draws from an archive of over 3,000 images taken by more than 300 women and men who participated in photography workshops I held in five prisons in Venezuela between 2010 and 2012. I have cared for this archive for fourteen years, with a sense of obligation to honor the creativity of the workshop participants. In the book, we could only present a small selection of images. The exhibition format allowed us to bring hundreds of images from this archive to light, in printed and digital form and in conjunction with audiovisual materials related to the workshops. This project has a long history. It took us seven years to publish the book, which is the basis for the exhibition. In Venezuela, there was little interest in a publication about incarcerated people who are common prisoners, not political detainees. Moreover, our project does not engage with narratives about gang-related violence or criminality, which dominate public discourse about criminal justice in Venezuela. Last year we finally found a partner for the book, Roga Ediciones, a small art publisher in Mexico City. And then, this past March at FotoFest Houston, I met Max Fields, director of the Visual Arts Center. I showed him the book and told him we wanted to bring our project to university spaces. We are grateful for the opportunity to do this exhibition at UT Austin.

ARTnews: Walking into the exhibition I was struck by the presentation of images at very different scales. There was also sound across the exhibition space. And we noticed a deliberate use of the colors pink and blue. Can you tell us about these curatorial choices? What did you expect viewers to experience?

Violette Bule: Una Luzevokes the notion of floating in an archive of images and words. Still images, moving images, written and spoken words. This is a collective archive without thematic categories or hierarchies and where images and words interrelate in indeterminate ways. Our intention was to foster a viewing experience that allows unexpected impressions and thoughts to arise. In terms of scale, the viewer walks around printed and digital images ranging in size from very small to monumental. Some images prompt you to get closer. Others require that you observe them at a distance. Curatorially, Una Luz is a gesture of liberation. After years confined to a small box that I’ve carried with me since I left Venezuela in 2014, these images are breathing free in a large public space. Our choice of colors for the typographic components is also part of this gesture. One of the photographs in the exhibition shows three women playing around with the word “LIBRES” (free) painted in red on a blue wall. They all wear pink uniforms that had been recently implemented by a newly appointed minister of prison affairs. Several women I met during the workshops told me how much they hated being forced to wear pink-colored uniforms. The imposition of that color on their bodies struck me as an act of humiliation rooted in gender stereotypes. As if this decorative measure could compensate for shameful living conditions in Venezuelan prisons. On the other hand, if you look closely, the font we chose for the prison slang words in the book and the exhibition resembles the typography of the word “LIBRES” in the photograph. We have borrowed these elements, particularly the color pink, to resignify them in an exhibition that argues for the creative dignity of incarcerated people.

Michel Otayek: The words you hear as you walk around the space come from a sound installation that Violette created specifically for the exhibition in collaboration with Mario Herrera. Mario was one of the participants in the workshops and he is also present in our book. In this sound installation, Violette and Mario recite prison slang words in tandem. This work has a spectral quality. Since it is set at low volume, it is not easy to make out the words being recited. This piece is in dialogue with other elements in the exhibition. The random display of slang words on screens across the gallery may help you identify some of the words you hear, but their meaning remains opaque. The idea is to situate viewers at a liminal space between murmur and words, on the edge of intelligibility. Una Luz presents multiple points of view about life under confinement in fluid relation to one another. Our hope is that visitors will experience something they didn’t expect and have an opportunity to revisit their assumptions about criminal justice, particularly if they have not been directly affected by incarceration. This happened to me years ago, when Violette invited me to collaborate with her on the book project. Through my immersion in the archive, I became aware of my misconceptions about carceral spaces. We are encouraged by the reception of the exhibition by the community at UT Austin, where we’ve participated in rich conversations about creativity and social justice. We’ve been moved to hear from students of diverse backgrounds that they were surprised to realize that Una Luz is an exhibition about joy.

ARTnews: Has the ongoing crisis in Venezuela impacted your collaboration on this project? How are recent events shaping public discourse about incarceration? Do you perceive a shift in general views about criminal justice in Venezuela?

Violette Bule: It is a tragic coincidence that our exhibition is on view at a moment of unprecedented political repression in our home country. The repression unleashed by the Maduro regime after the July 28th presidential elections is horrifying. Around 2,000 pro-democracy protestors have been arrested since then, including dozens of children. Numerous detainees have been subjected to inhumane treatment and torture. At the same time, the regime’s decision to send many political detainees to regular prisons, where they are being held alongside common prisoners, has led to a public outroar. This provocative decision and the outrage generated reveal an uncomfortable truth. In Venezuela, political detainees and common prisoners are often perceived as different categories of people. In public discourse, common prisoners are usually denied the human dignity accorded to political detainees. Questions about the purpose of incarceration or its relation to patterns of social and economic inequality are mostly absent from public discussion about criminal justice in Venezuela. My initial goal with the photography workshops was to prove their value as vocational training for social reinsertion. Based on my experience running week-long workshops in five different prisons, I prepared a detailed proposal for a permanent year-long program that could be implemented across the country. I submitted this proposal to the corresponding authorities but never received an answer. There is a famous quote by Nelson Mandela that illustrates our predicament: “No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails.” This painful moment in Venezuela may perhaps yield a more humane understanding about incarceration. We certainly hope that our focus on humanity and creative expression can contribute in some way to transforming the way we think and talk about carceral spaces.

Michel Otayek: When we began collaborating years ago, we agreed to stay away from politics. We did not want to take part in highly polarized debates about criminal justice in Venezuela, which are channeled through the filter of political conflict between the Maduro regime and the opposition and routinely denigrate incarcerated people. However, while we never wanted to politicize this project, we must take a stand and denounce the weaponization of the criminal justice system to suppress dissent in Venezuela. Moreover, in taking a stand for democracy and human rights in our native country, we also reject the dehumanizing rhetoric about Venezuelan migrants propagated by politicians in the United States. The vile characterization of migrants as “criminals” and “animals” rests on the assumption that incarcerated people are not human. We hope that our exhibition offers a platform for recognizing the fundamental dignity of every human being.

ARTNews: As Venezuelans living abroad, has the situation in your home country affected you personally or professionally?

Violette Bule: It’s hard to explain in a few words how leaving your country affects your life and career. When you leave, you lose the support of people and institutions who know you and your work. Emigrating creates a rupture in your artistic trajectory. I had plenty of experience in my field, but in the United States I had to start again from zero. I had to learn a new language, understand how different systems work, and rebuild my practice step by step. But these challenges prove your resilience and make you more adaptable. And they also nurture your work. That has certainly been my case. As an immigrant I have learned that identity evolves. You embrace precarity and lack of support as opportunities to rethink your personal and creative priorities. Some of my work specifically addresses the rise of populism in the United States and the stigmatization of immigrant and marginalized communities for political purposes. These are issues that affect me personally. I hope to one day be an active presence in my home country again, teach at a university, work with different communities and contribute my experience to reconceptualizing cultural networks and institutions. But not as binary choice. Being an immigrant forces you to challenge fixed notions of home, identity, and nation, and strive for a balance between where you came from and where you are now.

Michel Otayek: My career as an art historian has taken place entirely outside of Venezuela, which I left nearly 25 years ago. In this sense, my experience has been different from Violette’s. But questions of belonging have also shaped my research interests and the direction of my work. Venezuela’s descent into autocracy and chaos has been a very long process. My entire adult life has unfolded against the backdrop of a simultaneous sense of hope and despair about Venezuela, where part of my family continues to live. These conflicting emotions never leave you. But with Una Luz, it is hope that we hold on to.

“Una Luz: Photography Under Confinement in Venezuela” is on view until December 7 at the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

On First Day, Gallerists and Collectors Say Art Basel Miami Beach Has Its Energy Back

Sotheby’s Will Auction Stradivarius Violin from New England Conservatory With Estimate of $12 M.

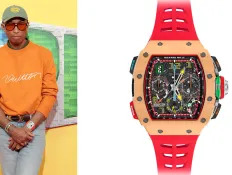

Pharrell Williams Is Auctioning Off a Signed Richard Mille Watch

Kelly Clarkson Brings Holiday Glamour in Alaïa Winter Coat to NBC’s 2024 Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree Lighting

‘If I saw this movie on a plane, I would still walk out’: The internet reacts to Disney’s Snow White trailer

NFLPA Exec Atallah Steps Down to Launch Advisory Firm