In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022, the Russian art scene saw an exodus of foreigners and locals alike. Russian artists, curators, filmmakers, and writers left the country in protest and several top figures at art institutions quit their jobs. Among the most prominent non-Russians, New Zealander curator Simon Rees quit his post as director of the Cosmoscow Art Fair and Italian curator Francesco Manacorda left his role as artistic director of V-A-C Foundation, an international arts nonprofit.

At the time, the UK’s then-culture secretary, Nadine Dorries, called culture the “third front” of the war, claiming that artistically isolating Russia could be as effective as economic sanctions. However, as the war nears its third year, a cohort of Italian curators, artists, and art historians, including Luca Tomìo and Alessandro Romanini, have bucked the trend of that isolation to participate or curate exhibitions there. The most recognizable Italian currently operating in Russia is Francesco Bonami, a curator and art critic whose impressive resume includes directing the 50th Venice Biennale and the 2010 Whitney Biennial. This year, Bonami has co-curated the exhibition “Square and Space. From Malevich to GES-2” at Moscow’s GES-2 House of Culture, which runs until October 27.

The GES-2 House of Culture is a massive 585,000-square-foot, privately backed arts center established in 2021 by V-A-C, which was founded by Leonid Mikhelson in 2009. With an estimated net worth of $24.1 billion, Mikhelson is one of Russia’s richest men, a close ally of Vladimir Putin, and was sanctioned by the UK government in 2022. While Mikhelson has not been sanctioned by the US, several companies and ships supplying his Novatek gas company are. He’s also a major shareholder of liquefied petroleum gas giant Sibur, which is also being squeezed by indirect US sanctions. Sibur supplies materials used in Russian military systems currently deployed in Ukraine, according to independent Russian media company Project. Novatek supplies gas to Russia’s Sverdlov Plant, which makes explosives and ammunition. The plant was sanctioned by the US in 2023.

In a recent conversation over WhatsApp with ARTnews, Bonami, who has worked with V-A-C for 14 years, rejected the idea that Mikhelson’s ties to the Russian military should disqualify the curator from working for GES-2. “Sorry, but the ethics of curating is a bullshit concept that I don’t indulge in,” Bonami said. “I could write a list of my colleagues who are collaborating with, to the say the least, ethically questionable people—but this is not the point … Sanctions are economic, not cultural. To sanction culture is a white crime that kills people’s souls.”

“I feel morally responsible to [GES-2’s] visitors,” Bonami continued. “They cannot travel abroad at their whims, unlike a few privileged [Russian] art world professionals. Without GES-2 and my work, these people will have no place to go and nothing to see. It’s my duty to continue.”

“In the art world, we are all more of less villains,” he added, arguing that no one boycotted British arts during the Falklands War in the 1980s.

Bonami is currently also heading up China’s contemporary art museum in Hangzhou, By Art Matters.

Several artists have cut ties with GES-2 since the start of the war, including Russian Evgeny Antufiev, who asked for his work to be removed from the museum. Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, whose theatrical piece examining US-Russian relations, Santa Barbara – A Living Sculpture, inaugurated GES-2, has also distanced himself from the museum.

Rees, who quit Cosmoscow via a scathing Facebook post that referred to Putin and his “clique” as “old-style cold warriors,” told ARTnews that while he would not return to Moscow unless Putin leaves power, he thinks it unlikely Bonami’s choice to work with GES-2 will hurt the curator’s reputation.

“Frankly, I don’t think any single curator, or any single artist, has the influence or power to change the current political climate inside Russia,” Rees said. “One senior curator doing a project at V-A-C makes no overall difference to the system. And in the case of someone like Bonami, who is very senior and at the end of his career, and with V-A-C deeply embedded in Italy [V-A-C also has a branch in Venice], I cannot see him suffering reputational damage.”

Meanwhile, Manacorda, who quit his job at V-A-C right after the all-out invasion of Ukraine, told ARTnews that he was wary of blacklisting Russians because of their government’s actions. “The Russian people are not its state. In addition, conflicts can be resolved only through dialogue—and cultural dialogue plays an absolutely central role in long-term diplomacy,” Manacorda, now the director of Castello di Rivoli in Turin, said. “However, in this moment, individuals need to make a choice between the urgency of not isolating the Russian people and their ethical position in relation to the conflict taking place between Ukraine and Russia.”

ARTnews asked Björn Geldhof, the director of Kyiv’s Pinchuk Art Center, what his reaction was when he heard that Bonami had accepted GES-2’s offer to curate the Malevich show. “It wouldn’t be polite of me to say,” he said. “If you are consciously working with Russians who have been sanctioned for not only supporting the Putin regime, but for directly supporting the war, by definition, you are also supporting the war. I think [Bonami’s involvement with GES-2] is deeply problematic… and disrespectful toward Ukrainians who are dying.”

Swedish curator Anders Kruger, who is the director of Kohta, a private kunsthalle in Helsinki, is on the same page as Geldhof.

“It’s extremely selfish for anyone to work for cultural institutions in Russia, which by definition are loyal to the regime, because otherwise they would close down during this period of open war with Ukraine,” Kruger told ARTnews. “I don’t see any justification at all to work with Russian institutions today.”

Konstantin Akinsha, a Ukrainian-American curator and writer, went so far as to describe Bonami’s participation in the GES-2 show as “a propaganda coup.”

“It’s hard to imagine that Bonami is unaware of the systemic repression of contemporary artists in Russia, who are being prosecuted en masse, thrown into prison, or forced to emigrate,” Akinsha told ARTnews. “Putin’s Russia is keen to prove that it is still internationally acceptable.”

Bonami is far from the only Italian arts professional choosing to continue to work with Russian institutions.

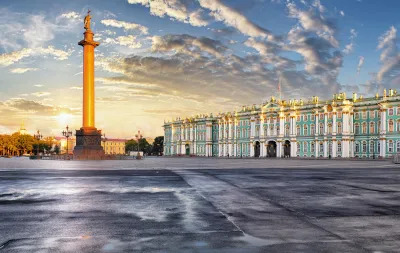

In early 2024, art historian Luca Tomìo helped organize the exhibition, “New Mysteries of the Paintings of Leonardo da Vinci,” at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, where he is listed on the website as a “scholarly consultant.”

That show was partly funded by businessman Konstantin Goloshchapov, another close Putin ally who is also a collector of religious art, many pieces of which were included in the exhibition. Meanwhile, the Hermitage’s director, Mikhail Piotrovsky, is yet another friend of Putin’s and an outspoken supporter of the war in Ukraine; he has since been sanctioned by Canada as a result. Piotrovsky’s son, Boris, is the deputy governor of St. Petersburg and, in 2022, he visited Russian-occupied Mariupol, the port city in eastern Ukraine that’s been razed to the ground by bombing.

In February, when the exhibition opened, Piotrovsky called it the museum’s “response to the challenges of the time.”

In the show, there are two paintings attributed to Da Vinci— The Battle of Anghiari and The Virgin of the Rocks—that three leading experts told BBC Russiain May are unlikely to be by the Renaissance master. Frank Zöllner, a German art historian and professor at Leipzig University, said, “Not a single serious researcher, that is, a qualified expert on Leonardo’s work, will support such an attribution.”

Another Italian curator who agreed to work in Russia after the war broke out was Alessandro Romanini, who specializes in African art. Romanini curated an exhibition titled “Reversed Safari: Contemporary Art from Africa,” which opened in St. Petersburg in 2023 as part of the Second Russia-Africa Economic and Humanitarian Forum.

(Neither Tomìo nor Romanini responded to requests for comment.)

The choice of whether to pursue projects in Russia is not limited to curators, but artists as well. Earlier this year, Italian photographers Edoardo Delille and Giulia Piermartiri accepted an invitation from the Moscow City-owned Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow (MAMM) to present their joint show, “Atlas of the New World.”

Running from April 13 to August 18, the show explored the consequences of climate change across the globe, showing images of people living in some of the most vulnerable regions, superimposed with visions of what those regions might look like by the end of the century. The exhibition was sponsored by Russia’s Norilsk Nikel, a serial polluter and the world’s largest producer of nickel and palladium. It was fined a record $2 billion by a Russian court for an Arctic oil spill in 2021. It is owned by Russia’s second-richest man, Vladimir Potanin, one more close Putin ally who was sanctioned by the US and the UK in 2022. Potanin also owns import-export company Normetimpex, which supplies nickel to make Russian military aircraft engines and cobalt to one of Russia’s largest nuclear facilities, Project also reported.

Delille told ARTnews that he was unaware that Norilsk Nikel had sponsored the show and said he believes that the Russian public should not be deprived of the arts due to the war in Ukraine.

“I totally don’t agree with Russia’s politics, of course I’m against the war, I don’t believe in war,” he said, noting that he and Piermartiri have been working on the exhibition since 2019 and that neither was paid anything by MAMM aside from travel expenses.

“We were invited to Moscow to talk about climate change. I spoke to loads of Russian kids—they are totally ashamed of what their government is doing [in Ukraine]. It’s not their fault. I’m Italian but I’m not a f—king fascist like my government. Unfortunately, my government is doing something I don’t like. So, I decided to go to Moscow to talk about my projects.”

Would Delille have collaborated with the museum had he known about Norilsk Nikel’s involvement? He’s not so sure, he said.

Russian artist Vadim Zakharov, who once represented Russia at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, has since vehemently protested the war. At the 2022 Venice Biennale, he held a banner reading, “the murder of women, children, [and] people of Ukraine is a disgrace to Russia”

In a recent interview, Zakharov told ARTnews his two ground rules for Western arts professionals to ethically work with Russian arts organizations: the projects must pursue “humanitarian and educational goals” and they should refuse money from organizations that are directly or indirectly linked to the conflict in Ukraine. However, he warned that even the “minimal activity” of Western curators and artists in Russia creates “a false sense that everything is fine and that there is no war.”

“I am not sure that such schizophrenia in the minds of the educated public is any worse than the war itself,” he said.