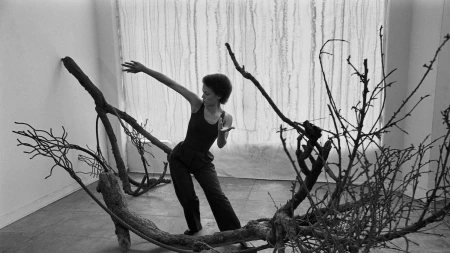

Courtesy of the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery, New York. Image: Adam Avila.

While it originated in New York in the 1960s with Black literary activist Amiri Baraka, the Black Arts Movement quickly gained traction in Southern California in the wake of the 1965 Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles. Drawing on new mediums flourishing on the West Coast, the Black Arts Movement as it manifested there put the focus on community uplift and radical change.

Yet, despite the fervent calls for unity during this period, the face of the Black Arts Movement in Los Angeles was overwhelmingly male, the contributions of Black women largely overlooked, sidelined, or silenced. As art historian Kellie Jones notes in South of Pico, her groundbreaking scholarship on the Southern California Black Arts Movement, “Black women were integral to both the struggles for Black freedom and women’s liberation. But as a number of writers have concluded, black women were expected to disregard the racism and class privilege of white feminism and turn a blind eye to the misogyny of Black Power.”

Despite these challenges with mainstream visibility, Black women artists and arts advocates in Los Angeles did manage to forge new pathways that circumvented sexism and racial bias, creating revolutionary work and spaces to show it. Here are five of them.

Read “Building Faith in the Future Part 1: The Rise of the Black Arts Movement in California” here.

-

Mary Ann Pollar

Image Credit: Courtesy Odette Pollar. In 1971, with her husband, Henry, Mary Ann Pollar founded the Rainbow Sign arts center in Berkeley—“a place to honor our past, to be aware of our present, and to build faith in our future,” as its brochure declared.

Invitation to the opening of the Rainbow Sign, August 21, 1971.

Rainbow Sign archive, courtesy of Odette Pollar

Pollar had honed her charismatic leadership style in the entertainment industry decades before opening the doors to Rainbow Sign. As a music promoter, she had introduced Bay Area audiences to musical icons like Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Curtis Mayfield, Odetta, Nina Simone, and Simon and Garfunkel.

Giving a platform to Black politicians and leaders in the Black Arts Movement, the Rainbow Sign presented musical acts, art exhibitions, and literary readings. During its six years in existence, the center was largely led by women who cultivated community, creating, as Pollard proudly proclaimed, “a Black table at which everyone is welcome to eat.” Central to this ethos of inclusion was the preservation of a Black culture conditioned not on assimilation but on autonomy and self-reliance.

Publicity material for Nina Simone’s performances at the Rainbow Sign, March 31-April 1, 1972.

Rainbow Sign archive, courtesy of Odette Pollar.

In 1975 Pollar and curator Evangeline Montgomery celebrated their longtime support of Black sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett as the Rainbow Sign artist of the year and persuaded the city of Berkeley to name the week of March 29 “Elizabeth Catlett Week.” Archived press material references Catlett’s work Black Unity (1968), a carved cedar sculpture showing a Black Power fist on one side and a pair of peaceful, smiling faces on the other. As Catlett explained at the time, “It’s the portrayal of a saying by Diego Rivera, ‘An open hand with its fingers spread is very weak, but a closed fist where all the fingers are together is very strong.’”

Elizabeth Catlett, Black Unity, 1968.

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Copyrght © 2023 Mora-Catlett Family/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Edward C. Robison III.

-

Ruth Waddy

Image Credit:

Museum of Nebraska Art Collection. Courtesy of the Museum of Nebraska Art.Montgomery fostered deep relationships with artists, particularly arts advocate Ruth Waddy, whose stewardship and cultivation of Black visual art in Los Angeles in the 1960s led her to create Art West Associated, an organization that promoted the representation of Black artists in museums and galleries.

Waddy was an artist in her own right, creating linocut prints whose subject matter ranged from the political to the quotidian. She came to art well into her fifties after an early retirement as a Los Angeles County clerk. Noteworthy among her prints were The Key (1969) featuring six Black men walking toward a group of armed individuals, signaling the shift from passive protest to armed resistance, and The Exhorters(1976). Depicting two Black men, fists raised, energetically speaking to a crowd, The Exhorters referenced the tactical and strategic directives that Black nationalists were espousing. Waddy’s travels also gave her the opportunity to amplify the work of other Black artists and to collect their stories. She collaborated with scholar Samella Lewis to edit Black Artists on Art, published in two volumes in 1969 and 1971.

-

Betye Saar

Image Credit: Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. Courtesy of the artist and Roberts Projects Los Angeles. In 1972 Betye Saar responded to a call for artworks from the Rainbow Sign. Long before the birth of the Black Arts Movement, Saar had established a successful career in in design and printmaking, then evolved into one of the forebears of California assemblage art. Her work combined elements of cosmology, mysticism, Southern African-American folklore, and political commentary. (And it still does: at 96 years old, Saar continues to create art that reflects the way she experiences the world.)

In response to the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. the Rainbow Sign, which attracted such luminaries as Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, Jayne Cortez, Elizabeth Catlett, Shirley Chisholm, Nina Simone, and Alice Walker, was organizing a show about Black heroes. It was at this exhibition that Saar debuted what would become an infamous work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, a shadow-box assemblage consisting of a mammy figurine placed against a backdrop of multiple images of a smiling Aunt Jemima.

Resting in the statuette’s left hand is the barrel of a longneck rifle; a broom in her right hand partially conceals a small pistol. In front of her is a postcard of another mammy figure holding a porcelain-white baby. In the center of the work Saar placed a large Black Power fist that subverts the air of servitude conveyed in the postcard. With this piece, Saar upended racist iconography by empowering her subjects with tools of resistance that release them from oppression.

-

Maren Hassinger

Image Credit: Courtesy of the artist and Susan Inglett. Maren Hassinger took a much more conceptual approach to Black art. As a trained dancer growing up in Los Angeles, Hassinger studied sculpture and obtained her MFA in Fiber Arts at UCLA. Still active as an artist, she seamlessly combines these three art forms in sculptures and performances that simulate the harmonies between the body and the natural world. Rituals are integral in her practice as she draws on the energies of communal art-making processes like weaving and crafts to transform everyday objects like newspaper strips and trash bags into symbolic gestures of love, healing, and hope.

-

Senga Nengudi

Image Credit: Quaku/Roderick Young. Courtesy of the artist, Sprüth Magers, Berlin, London, and Los Angeles, and Thomas Erben Gallery, New York. Another artist who expressed herself through dance was Senga Nengudi, who was living in West Los Angeles during the 1965 Watts Rebellion and was influenced by the sea change that subsequently took place within the arts community. Performance is just one element of Nengudi’s diverse art practice, and its ephemerality lends itself to her enigmatic persona. Her specialty is shape shifting, as she combines common, everyday materials like water, sand, and pantyhose into clever visual metaphors on bodily strength and resilience.

In a 2013 oral history interview, Nengudi reflected on the riots: “It was truly an issue of a phoenix rising, because it really galvanized the arts community and it really became a family affair. You had a sense of being a part of something.” This was particularly apparent among writers and poets who formed groups like the Watts Writers Workshop. “The mind-set became different,” Nengudi recalled. “We no longer want to knock on the door; we want to create something for ourselves. And if we have to support that we will support it within ourselves.”

In the post-riot years, Nengudi taught at the Watts Towers Arts Center with Noah Purifoy, after which she moved to Japan and then to New York. In the 1970s she returned to Los Angeles, where she was a founding member of Studio Z, a performance collective supported in part by CETA, the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act program.

Nengudi, Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins, David Hammons, Barbara McCollough, and other members of Studio Z frequently gathered in Hammons’s studio space, a former ballroom on Slauson Avenue. The studio functioned as a workshop, music venue, meeting space, and artist salon where members discussed concepts and experimented with new materials and technology. Studio Z also held spontaneous performances and happenings in public spaces.

In Nengudi’s 1978 piece titled Ceremony for Freeway Fets,the artist orchestrated a gathering of dancers, musicians, and artists who performed beneath a freeway underpass whose tall pillars were topped with garlands Nengudi made from bundled pantyhose and fabric. Rising from the dirt, the concrete cylinders evoked palm trees sprouting from soil. Nengudi crowned performers in masks and headdresses constructed from the same knotted fabric and ceremonial robes made from unconventional materials. The performance, which lasted an hour, melded Yoruba rituals with Japanese avant-garde performance as participants danced to live musicians.

-

These women are getting their deserved, yet belated recognition in comprehensive group shows like “We Wanted a Revolution,” mounted several years ago at the Brooklyn Museum, and “Soul of a Nation,” shown at the Broad in Los Angeles. Betye Saar has a traveling exhibition of work she created in the 1980s and 1990s titled “Serious Moonlight,” currently on view in Switzerland at the Kunstmuseum Luzern. Nengudi is the 2023 recipient of the Nasher Prize from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and has concurrent solo shows at Dia Beacon and Sprüth Magers in New York opening in May. As present-day artists continue to grapple with the same challenges as their predecessors, the work of these trailblazers continues to inspire new artistic voices committed to charting their own paths forward.

Mary Ann Pollar

In 1971, with her husband, Henry, Mary Ann Pollar founded the Rainbow Sign arts center in Berkeley—“a place to honor our past, to be aware of our present, and to build faith in our future,” as its brochure declared.

Rainbow Sign archive, courtesy of Odette Pollar

Pollar had honed her charismatic leadership style in the entertainment industry decades before opening the doors to Rainbow Sign. As a music promoter, she had introduced Bay Area audiences to musical icons like Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Curtis Mayfield, Odetta, Nina Simone, and Simon and Garfunkel.

Giving a platform to Black politicians and leaders in the Black Arts Movement, the Rainbow Sign presented musical acts, art exhibitions, and literary readings. During its six years in existence, the center was largely led by women who cultivated community, creating, as Pollard proudly proclaimed, “a Black table at which everyone is welcome to eat.” Central to this ethos of inclusion was the preservation of a Black culture conditioned not on assimilation but on autonomy and self-reliance.

Rainbow Sign archive, courtesy of Odette Pollar.

In 1975 Pollar and curator Evangeline Montgomery celebrated their longtime support of Black sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett as the Rainbow Sign artist of the year and persuaded the city of Berkeley to name the week of March 29 “Elizabeth Catlett Week.” Archived press material references Catlett’s work Black Unity (1968), a carved cedar sculpture showing a Black Power fist on one side and a pair of peaceful, smiling faces on the other. As Catlett explained at the time, “It’s the portrayal of a saying by Diego Rivera, ‘An open hand with its fingers spread is very weak, but a closed fist where all the fingers are together is very strong.’”

Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Copyrght © 2023 Mora-Catlett Family/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photography by Edward C. Robison III.

Ruth Waddy

Museum of Nebraska Art Collection. Courtesy of the Museum of Nebraska Art.

Montgomery fostered deep relationships with artists, particularly arts advocate Ruth Waddy, whose stewardship and cultivation of Black visual art in Los Angeles in the 1960s led her to create Art West Associated, an organization that promoted the representation of Black artists in museums and galleries.

Waddy was an artist in her own right, creating linocut prints whose subject matter ranged from the political to the quotidian. She came to art well into her fifties after an early retirement as a Los Angeles County clerk. Noteworthy among her prints were The Key (1969) featuring six Black men walking toward a group of armed individuals, signaling the shift from passive protest to armed resistance, and The Exhorters(1976). Depicting two Black men, fists raised, energetically speaking to a crowd, The Exhorters referenced the tactical and strategic directives that Black nationalists were espousing. Waddy’s travels also gave her the opportunity to amplify the work of other Black artists and to collect their stories. She collaborated with scholar Samella Lewis to edit Black Artists on Art, published in two volumes in 1969 and 1971.

Betye Saar

In 1972 Betye Saar responded to a call for artworks from the Rainbow Sign. Long before the birth of the Black Arts Movement, Saar had established a successful career in in design and printmaking, then evolved into one of the forebears of California assemblage art. Her work combined elements of cosmology, mysticism, Southern African-American folklore, and political commentary. (And it still does: at 96 years old, Saar continues to create art that reflects the way she experiences the world.)

In response to the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. the Rainbow Sign, which attracted such luminaries as Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, Jayne Cortez, Elizabeth Catlett, Shirley Chisholm, Nina Simone, and Alice Walker, was organizing a show about Black heroes. It was at this exhibition that Saar debuted what would become an infamous work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, a shadow-box assemblage consisting of a mammy figurine placed against a backdrop of multiple images of a smiling Aunt Jemima.

Resting in the statuette’s left hand is the barrel of a longneck rifle; a broom in her right hand partially conceals a small pistol. In front of her is a postcard of another mammy figure holding a porcelain-white baby. In the center of the work Saar placed a large Black Power fist that subverts the air of servitude conveyed in the postcard. With this piece, Saar upended racist iconography by empowering her subjects with tools of resistance that release them from oppression.

Maren Hassinger

Maren Hassinger took a much more conceptual approach to Black art. As a trained dancer growing up in Los Angeles, Hassinger studied sculpture and obtained her MFA in Fiber Arts at UCLA. Still active as an artist, she seamlessly combines these three art forms in sculptures and performances that simulate the harmonies between the body and the natural world. Rituals are integral in her practice as she draws on the energies of communal art-making processes like weaving and crafts to transform everyday objects like newspaper strips and trash bags into symbolic gestures of love, healing, and hope.

Senga Nengudi

Another artist who expressed herself through dance was Senga Nengudi, who was living in West Los Angeles during the 1965 Watts Rebellion and was influenced by the sea change that subsequently took place within the arts community. Performance is just one element of Nengudi’s diverse art practice, and its ephemerality lends itself to her enigmatic persona. Her specialty is shape shifting, as she combines common, everyday materials like water, sand, and pantyhose into clever visual metaphors on bodily strength and resilience.

In a 2013 oral history interview, Nengudi reflected on the riots: “It was truly an issue of a phoenix rising, because it really galvanized the arts community and it really became a family affair. You had a sense of being a part of something.” This was particularly apparent among writers and poets who formed groups like the Watts Writers Workshop. “The mind-set became different,” Nengudi recalled. “We no longer want to knock on the door; we want to create something for ourselves. And if we have to support that we will support it within ourselves.”

In the post-riot years, Nengudi taught at the Watts Towers Arts Center with Noah Purifoy, after which she moved to Japan and then to New York. In the 1970s she returned to Los Angeles, where she was a founding member of Studio Z, a performance collective supported in part by CETA, the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act program.

Nengudi, Hassinger, Ulysses Jenkins, David Hammons, Barbara McCollough, and other members of Studio Z frequently gathered in Hammons’s studio space, a former ballroom on Slauson Avenue. The studio functioned as a workshop, music venue, meeting space, and artist salon where members discussed concepts and experimented with new materials and technology. Studio Z also held spontaneous performances and happenings in public spaces.

In Nengudi’s 1978 piece titled Ceremony for Freeway Fets,the artist orchestrated a gathering of dancers, musicians, and artists who performed beneath a freeway underpass whose tall pillars were topped with garlands Nengudi made from bundled pantyhose and fabric. Rising from the dirt, the concrete cylinders evoked palm trees sprouting from soil. Nengudi crowned performers in masks and headdresses constructed from the same knotted fabric and ceremonial robes made from unconventional materials. The performance, which lasted an hour, melded Yoruba rituals with Japanese avant-garde performance as participants danced to live musicians.

These women are getting their deserved, yet belated recognition in comprehensive group shows like “We Wanted a Revolution,” mounted several years ago at the Brooklyn Museum, and “Soul of a Nation,” shown at the Broad in Los Angeles. Betye Saar has a traveling exhibition of work she created in the 1980s and 1990s titled “Serious Moonlight,” currently on view in Switzerland at the Kunstmuseum Luzern. Nengudi is the 2023 recipient of the Nasher Prize from the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas and has concurrent solo shows at Dia Beacon and Sprüth Magers in New York opening in May. As present-day artists continue to grapple with the same challenges as their predecessors, the work of these trailblazers continues to inspire new artistic voices committed to charting their own paths forward.

RobbReport

From a Two-Person Submarine to an Electric Surfboard: 7 High-Tech Water Toys for Your Superyacht

WWD

Jelena Djokovic Gets Shady in Cat-eye Sunglasses and Self-Portrait Blazer Dress for Husband Novak’s Wimbledon 2023 Men’s Singles Final Match

BGR

Google Pixel Fold review: My favorite foldable, but not quite the best

Sportico

Braves Spin-Off Positions Liberty Media for Tax Break, Team Sale

SPY