Carl Andre, a sculptor who was among the foremost artists associated with the Minimalist art movement of the 1960s, died on Wednesday at 88. His death was confirmed by Paula Cooper Gallery, his longtime New York representative.

“Carl Andre redefined the parameters of sculpture and poetry through his use of unaltered industrial materials and innovative approach to language,” the gallery wrote in its announcement. “He created over two thousand sculptures and an equal number of poems throughout his almost seventy-year career, guided by a commitment to pure matter in lucid geometric arrangements.”

Andre was among the Minimalists who stripped sculpture to its bare essentials, paring the medium down until it existed simply as forms made from industrial materials that were not intended to evoke any emotions. He received praise for his art of the 1960s and ’70s, only to face scrutiny during the late ’80s when he faced trial for the death of his partner, the artist Ana Mendieta.

In 1988, Andre, who was accused of murdering Mendieta, was acquitted after a bench trial. Yet many have continued to put forward theories about Mendieta’s death that implicate Andre, with curator Helen Molesworth doing a podcast about the subject last year.

These allegations have not kept Andre’s work from being exhibited widely in museums. His “Elements” series, featuring sculptures formed from uniformly sized red cedar blocks arranged in various ways, are still considered hallmarks of Minimalism, as are his “Plains” and “Squares” sculptures, crafted from steel and aluminum plates and magnesium, respectively.

The Dia Art Foundation organized an Andre retrospective in 2014; it went on to travel to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. An exhibition of his work was recently on view at the Daegu Art Museum in South Korea.

Andre himself once said that his work is “close to zero,” in that it was non-representational and deliberately devoid of affect. He, alongside other members of the Minimalist movement, was essential in bringing art in an increasingly conceptual direction—away from the visual, into the realm of ideas.

But Andre’s work, unlike that of other Minimalists like Donald Judd and Dan Flavin, was hard, steely, and severe. Critic Peter Schjeldahl once put it bluntly in a review of one Andre show: “Andre is not much fun.” That Andre rarely gave interviews on the record—both during his rise to fame in New York and after it, in the later stages of his career—seemed only to reinforce the idea of a flinty thinker whose art mirrored his psyche.

“You have to really rid yourself of those securities and certainties and assumptions and get down to something which is closer and resembles some kind of blankness,” Andre told critic Phyllis Tuchman in a 1970 Artforum interview. “Then one must construct again out of this reduced circumstance. That’s another way, perhaps, of an art poverty; one has to impoverish one’s mind. This is not a repudiation of the past or such things, but it is really getting rid of what I describe as dross.”

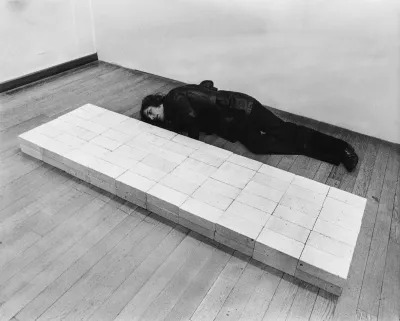

Many of his sculptures feature objects arrayed according to rigorous rubrics that allowed for little room for variation. His “Equivalent” series, begun in 1966, is a grouping of rectangular arrangements of firebricks. Each element has the same exact size, shape, and weight; they appear factory-produced, as though Andre had never touched them.

Their industrial look and feel was in some ways the point. Art historians have drawn parallels between Andre’s sculptures and Constructivism, the Russian avant-garde movement of the 1910s that saw no division between art and labor, though Andre dismissed a lot of the theories surrounding his art.

Adding to the unadorned appearance of these works is their unusual presentation style. They are exhibited on the floor, without a pedestal to uphold them as had historically been the case for a sculpture or an art object of note. In Andre’s hands, these firebricks constituted something that ought not to be worshipped, as most art objects might: viewers could walk on them, trodding over these sculptures as though they were just another part of their art spaces’ architecture.

But for many, these objects have been tough to admire after the death of Mendieta, the Cuban-born artist who fell from a window in 1985. Critic Calvin Tomkins, in a lengthy profile of Andre published in the New Yorker in 2011, wrote, “It is hard to think of an artist whose career has been so affected by circumstances that have nothing to do with his art.”

Protests have continued to follow his shows. The feminist collective the Guerrilla Girls once labeled him “the O.J. of the art world.” In 2015, during the Dia retrospective, a group of performers staged an action in which they walked through the show and cried for 20 minutes. The event was billed as “a public cry-in/silueta party,” a reference to Mendieta’s “Silueta” series, for which she sought to explore the relationship between her body and the natural world.

Carl Andre was born in 1935 in Quincy, Massachusetts. Andre told Tomkins that his childhood was “almost feral,” in that he was given free rein to play as he liked by his parents. His good grades in public school earned him a scholarship to the Phillips Academy in Andover, which put him on the path to becoming an artist.

He had plans to study art at Kenyon College in Ohio, but he was so bored by the offerings that he stopped attending classes and was kicked out after just two months. An itinerant period followed in which Andre spent a year in London, then some time in the US Army’s intelligence unit. With his stint in the Army over, he attended Northeastern University, but he hated that school, too, and quickly departed for New York.

In 1958, Andre struck up a friendship with the artist Frank Stella, and the two would continue to push each other’s art toward the styles that would make them famous. Stella was the one who told Andre to bring found timber to his studio—the wood was too big to fit in the apartment Andre shared with the filmmaker Hollis Frampton. Andre then hit a beam of it with a mallet, shaping it into a rough-hewn form that roughly recalled a famed Constantin Brancusi sculpture. When Andre did so, Stella examined it and told him he had created another kind of sculpture.

While critics fell hard for Andre’s art, the public found reasons to hate it. When the Tate in London dropped $1,000 on an “Equivalents” work in 1976, there was an outcry. The year afterward, the state of Connecticut bought an Andre piece consisting of 36 uncut boulders for $87,000, raising further ire. Hartford’s mayor blamed Andre for bringing his city “international ridicule.”

For some, an entirely new reason to detest Andre emerged in 1985, when Mendieta fell from the window of his Mercer Street studio in Manhattan. The two had become romantically involved in 1979 and married in 1985.

On the night that she died at age 36, they had an argument. In the 911 call Andre made to the police, he said that they “had a quarrel about the fact that I was more, eh, exposed to the public than she was. And she went to the bedroom, and I went after her, and she went out the window.” Lawyers during his 1988 trial presented evidence that she had consumed alcohol that night. A doorman testified that he heard cries of “No, no, no!” just before her body hit the ground.

Andre was charged with murder, and many in the art world rose to his defense, though Andre discouraged his supporters from attending the trial, where evidence against him was presented by the prosecution. He was acquitted, and as he exited the courtroom, he said, “Justice was served. Justice was served.”

Despite Andre having emerged from the trial legally unscathed, Mendieta’s death continues to be painful subject, repeatedly coming up any time a major show of his work is mounted in the US. It negatively impacted Andre after the trial, spurring him to spend significant amounts of time abroad for several years. Yet it does not appear to have hurt his career in the more recent years. In 2013, he appeared in the Venice Biennale, the most important recurring art exhibition in the world.

He is survived by his wife, the artist Melissa L. Kretschmer, and his sister, Carol.

Many continue to speak about Andre’s work in lofty terms. More generally, scholars have theorized quite a bit about Andre’s use of space and form. But Andre, for his part, once said of all that writing, “I thought that was nothing but bullshit.”