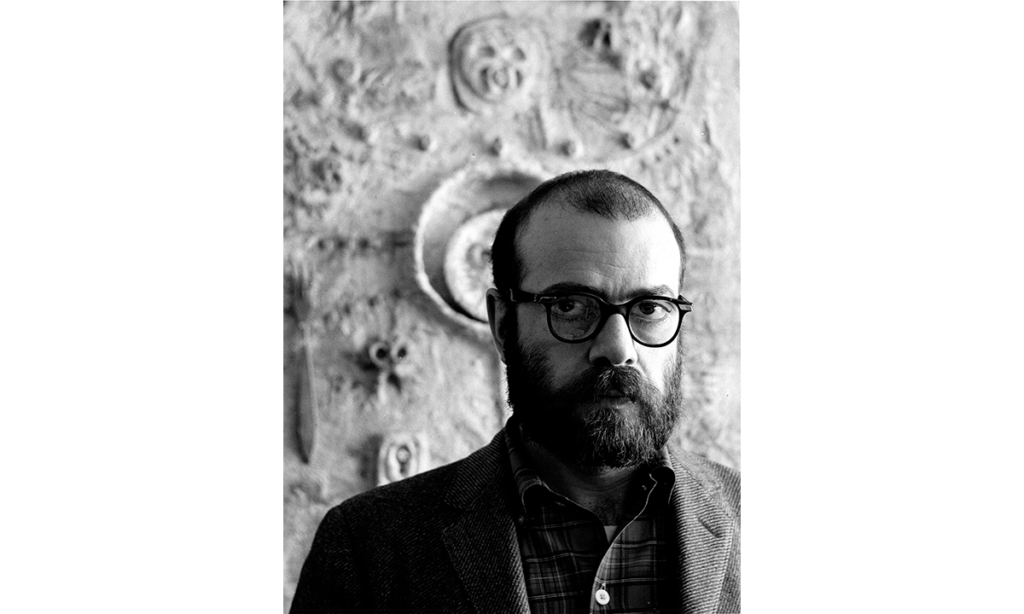

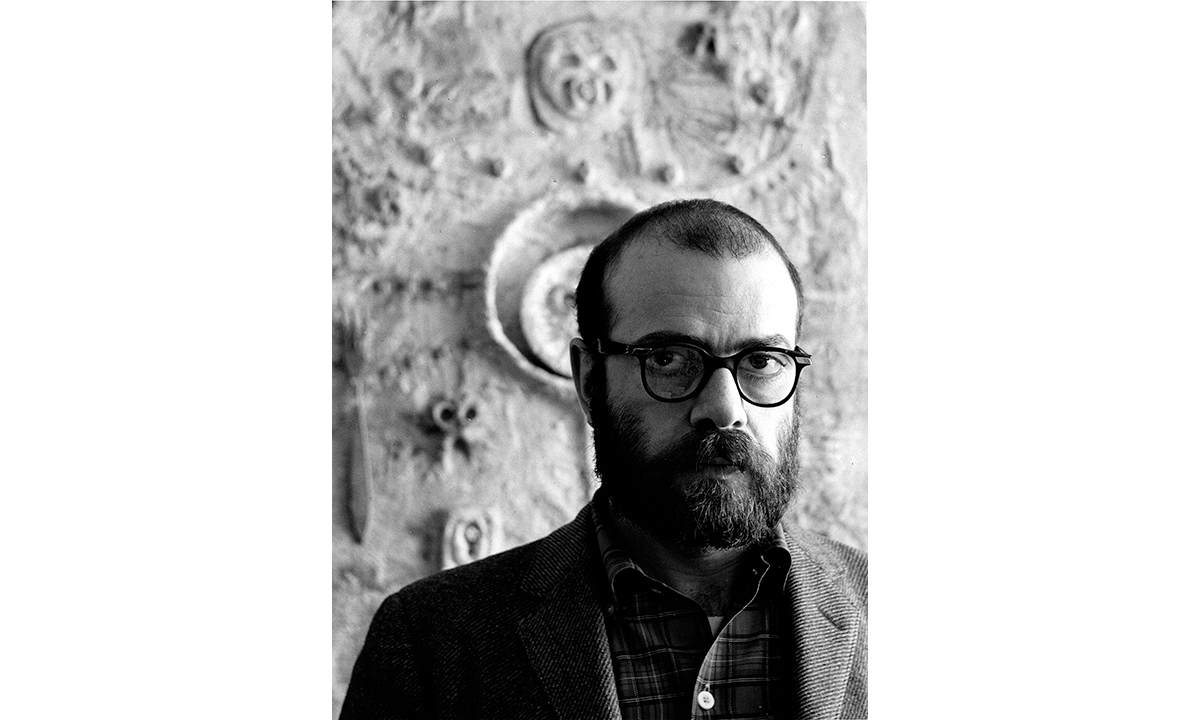

Dominick Di Meo, an artist who shook up Chicago’s art scene in the 1960s with surreal paintings and collages, only to gain a following far beyond the city late in his career, has died at 97. His death was announced on Sunday by his Chicago gallery, Corbett vs. Dempsey.

Di Meo was among the Chicagoan artists who during the ’60s plotted a new, off-kilter course of art-making that shared little in common with the Pop art and Minimalism emerging from New York. Neither totally abstract nor totally figural, his works from this era were part of an effort to inject new energy into Chicago, whose artistic scene he said was “dead creatively.”

He was a member of the Monster Roster, a group of artists who worked in figuration at a time when abstraction still dominated. Many of them looked to ancient mythologies to obliquely comment on the world’s current condition. Through this loose group, he became close with artists such as Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, and June Leaf.

Born in 1927 in Niagara Falls, New York, to Italian immigrant parents, Di Meo battled polio at a young age, leaving him with a lasting interest in death and the body. In an interview with curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, he credited his turn to art with an experience had in a polio ward. Wrapped up in a plaster cast and unable to move, Di Meo received free toys, only to see them taken away from him by a nurse. Frustrated by that experience, he developed a desire to use his hands to create.

He came to Chicago to study at the School of the Art Institute, receiving an undergraduate degree in 1952. When he first matriculated, he wanted to become a landscape painter, but he emerged working in a more experimental mode.

Di Meo looked to 20th-century avant-gardes like Dada and Surrealism, much as New York artists did, drawing ready-made objects into his paintings and developing private symbologies. He looked, too, to painters like Jean Fautrier and Jean Dubuffet, who deliberately left their surfaces rough and unappealing to the eye.

But Di Meo took equal inspiration from Aztec, African, and Mayan art on view at Chicago’s Field Museum. “We were all turned on by it, it was a big learning experience,” he told Obrist.

Many of Di Meo’s works from the ’60s are off-kilter and tough to parse. Satie by Moonlight (1966), a painting owned by the Art Institute of Chicago, features a painted figure with a moon-shaped head; it wears an actual, used T-shirt. Somnabulator (1964), one of the works Di Meo painted following a brief period in his parents’ homeland of Italy, portrays a sleepwalker whose body splits apart, forming multiple heads with gaping mouths.

Di Meo relocated to New York in 1969, taking up residence in SoHo five years later. In 2007, well after SoHo had been gentrified, Di Meo told the New York Times that he had never much wanted to move there, given that so many artists were there already. Yet he stayed for much of his career.

In SoHo, Di Meo encountered scraps of fabric, mesh cloth, and other pieces of trash, which he harvested and turned into oddball sculptural works. He told the Times that the neighborhood offered “a gold mine for an assemblage artist who just wanted to put things together.”

Despite having featured in group shows early on at the Art Institute of Chicago and what was then the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, and despite having received a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1972, Di Meo did not mount many solo shows after the ’70s. His CV contains a 26-year gap between 1982 and 2008, the year that Corbett vs. Dempsey mounted his first solo show.

After that, Di Meo began to receive greater recognition. He had a solo show with London’s blue-chip Thomas Dane Gallery in 2013 and another one-person show at the trendsetting JTT gallery in New York in 2017. Artists many generations his younger began looking at his work, too. Earlier this year, New York’s Simone Subal Gallery paired works by Di Meo from the ’90s with new paintings by Ella Rose Flood, a Chicago-based artist in her 20s.

Yet Di Meo always seemed to revel in his outsider status, so fame did not much interest him. Speaking of SoHo’s artistic exodus, he told the Times in 2007, “It’s nicer now that most of the artists have left. Artists are prima donnas, you know.”