The Great Depression began in the United States with the stock market crash in October 1929, which instigated a severe worldwide economic downturn. President Franklin Roosevelt responded with a series of programs and reforms called the New Deal to promote economic recovery and alleviate financial strain across various labor sectors, including farming and migrant labor. To get a comprehensive understanding of the depth of economic distress that workers faced, the government established a number of administrative bodies to document the nation’s social and financial landscape, both visually and through the written word. Among these documentarians was photographer Dorothea Lange, whose mission to capture the physical and psychological toll of the Depression on small farmers and laborers inspired countless future photojournalists and social activists, and helped the country come to terms with the economic reality of the day.

Born in 1895, in Hoboken, New Jersey, Lange—whose work is currently the subject of an exhibition at the National Gallery in Washington, DC—did not begin her career as a champion for social justice with her lens pointed at the most disadvantaged Americans. Her entrée into image making began in New York City, at Columbia University, where she studied with Clarence H. White, a fine art photographer and compatriot of Alfred Stieglitz. Later, still in New York, she worked as a studio assistant for the pictoralist photographer Arnold Genthe, who counted among his clientele the most recognizable names of the early 20th century, including Greta Garbo, Senator Robert La Follette Sr., Gene Tunney, and President Woodrow Wilson.

Later, in 1919, she moved to San Francisco, where she opened a photo studio that catered to the rich and famous of her own era, and ran it successfully for a decade. It was only in 1929, after the stock market crash paralyzed the global economy, that Lange began to document the harsh realities of American life on the streets of her adopted hometown.

After seeing firsthand the hardship imposed by the Depression, the rampant homelessness, the men in breadlines, Lange became an advocate for social justice, believing that an image could have the power to change the lives of the less fortunate.

Around this time, in the early 1930s, Paul Schuster Taylor, a professor of agricultural economics at the University of California, Berkeley, was working for the State Emergency Relief Administration, researching migrant laborers’ influx into California seeking farm work. After seeing Lange’s images, he sought permission to use one, and soon hired her to illustrate his reports about the terrible conditions these people suffered.

Agricultural reform was of paramount importance to Roosevelt when he took office in 1933. He swiftly established the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, which benefited primarily large landholding farmers, leaving small farmers, tenant laborers, and migrant workers to struggle.

To address worsening economic conditions, Roosevelt also founded the Federal Emergency Relief Administration in 1933 to provide federal funding to states for relief efforts. However, the funding often fell short of long-term needs, highlighting the inadequacy of relief efforts. Recognizing the need for more cohesive agrarian assistance, Roosevelt created the Resettlement Administration in 1935, later renamed the Farm Security Administration (FSA).

With assistance from Taylor, who became her second husband (in New York she’d married the painter Maynard Dixon), she collaborated from 1935 to 1945 with multiple agencies in Roosevelt’s New Deal government, including the FSA, the Bureau of Agricultural Economics, the War Relocation Authority, and the Office of War Information. Like her fellow documentarians, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, and Ben Shahn, she traveled the United States for years, photographing the lives of those worst hit by the Depression.

Lange’s partnership with these agencies raises questions about the intent and ethics behind her photographs. Were they mere propaganda tools to garner support for government programs, or did they genuinely serve as evidence of dire need?

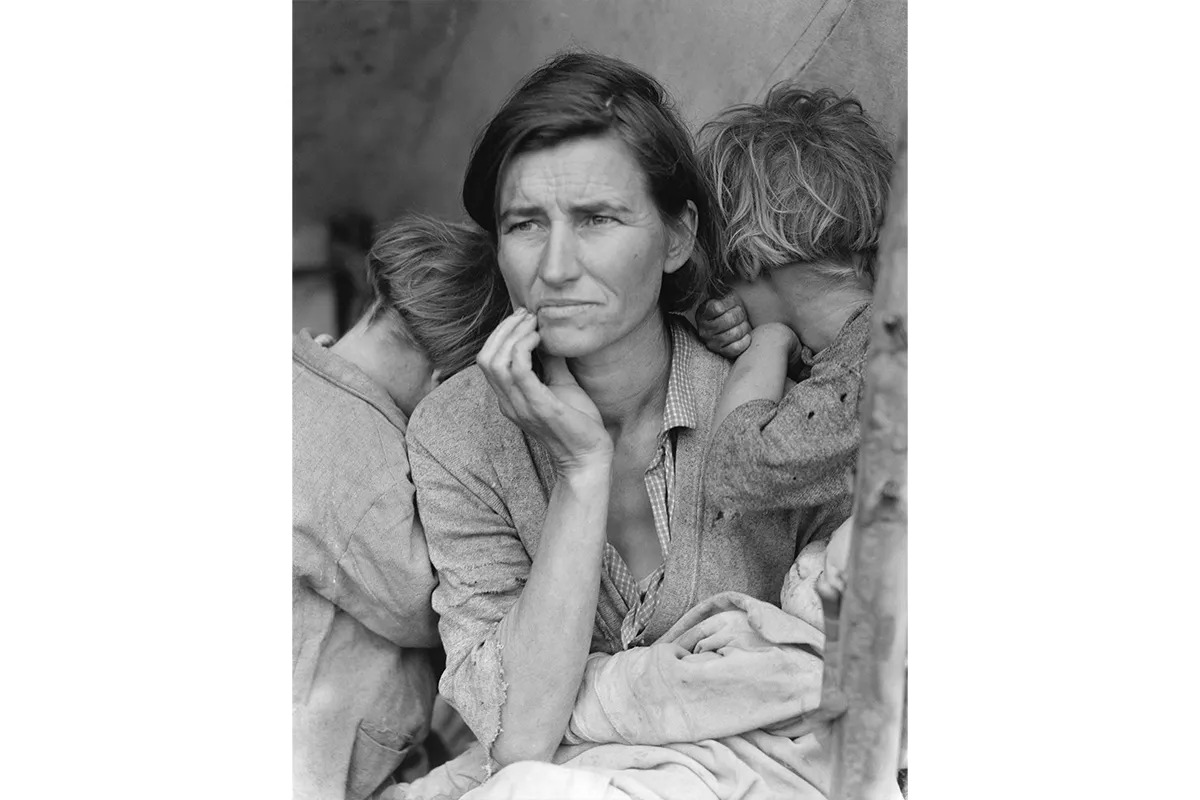

Lange’s most important photograph is Migrant Mother, an image that stands as an enduring symbol of an era fraught with despair and hardship. Captured in 1936, the picture embodies the collective struggle and resilience of American families during one of the nation’s most challenging epochs.

The image portrays Florence Owens Thompson and her children, offering a poignant glimpse into the everyday reality of poverty, destitution, and the pervasive struggle for survival experienced by countless families during that era. Its significance lies not only in the personal plight of the individuals depicted but in its representation of the larger social and economic turmoil.

The photograph became a touchstone for humanizing the widespread plight of Depression-era families. It brought visibility to the unseen and humanized the statistics, allowing viewers to connect emotionally with the harsh realities these families faced. The picture also proved a testament to the power of documentary photography to drive social change. Its impact was profound, leading to an awakening of public consciousness and influencing government policy. Following its circulation, the image spurred the government to act, resulting in the initiation of further aid programs for migrant agricultural workers and their families.

Migrant Mother is often celebrated for its artistic merit. Lange’s composition, use of light, and the profound emotional depth she captured contribute to its enduring legacy as a work of art. It’s a striking combination of visual storytelling and artistic finesse that elevates it from mere snapshot to a profound and evocative portrayal of an era. It stands as a poignant and powerful symbol of the adversity Americans faced during an unforgiving time, and its enduring legacy underscores the potency of visual storytelling in revealing truths, stirring emotions, and bringing about societal change.

Some critics have nevertheless questioned the authenticity of Lange’s work, and particularly Migrant Mother; they claim she staged or manipulated the scenes she photographed. Despite being known for documenting her subjects’ stories as well as their images, she collected very little information this time.

Lange came across the woman who would become the Migrant Mother and her family while driving home from a photo shoot of migrant laborers who had traveled West in search of farm work during the Depression. Along the way, she passed a sign for a pea-pickers camp. She drove by, but 20 minutes later, impulse made her turn around. By many accounts, Lange stayed no longer than 10 minutes, and left with the assumption that Thompson was among those seeking work among the California pea farms where she had just been photographing.

But that wasn’t the case. Thompson and her family were simply traveling, and had encountered car trouble. Thompson was waiting while her husband and son walked to the nearest town in search of help. Decades later, Thompson told her local newspaper she’d regretted ever allowing Lange to photograph her, and felt that her image had been misused.

“I wish she hadn’t taken my picture,” she said. “I can’t get a penny out of it. [Lange] didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

A MoMA One on One Series paperback by Sarah Meister reveals how tangled the history of Migrant Mother is. According to Meister, Thompson was a full-blooded Cherokee, a fact that, had it been known at the time, would likely have changed how the photograph was received by the general voting public. Ironically, Thompson was against the government support that Lange’s picture was meant to stimulate. In the book, Thompson’s son Troy Owens said her “biggest fear was that if she were to ask for help [from the government], then they would have reason to take her children away from her. That was her biggest fear all through her entire life.”

A description on MoMA’s own website calls the work “the single most recognizable image from the Great Depression,” yet inaccurately describes Thompson and her children as “huddled together in a tent at a pea-pickers’ camp in Nipomo, California.”

In an interview with the New York Times, Meister proposed a theory as to why Migrant Mother is so often described incorrectly. The image appeared in a story filed by a United Press reporter who visited the Nipomo pea farms a few days after Lange and Thompson had gone their separate ways. When that story was published, the photograph was captioned with information from the United Press reporter’s story.

Since the invention of photography, there have been questions of veracity in photojournalism; a photographer chooses what to include, and exclude, before shooting the image. Still, there is little question that the portrait has come to represent the generation of Americans who suffered through the Great Depression, which speaks to the influence of photography and how images can be interpreted.

While Lange’s most popular images (those chosen by the government agencies who employed her) depict destitution, they often conveyed resilience and determination, and celebrated the strength of those enduring hardship, including African American farmers who faced discrimination in government relief efforts.

In 1941 Lange received a Guggenheim fellowship to continue her work for the FSA and make “documentary photographs of the American social scene, particularly in rural communities.” She chose however to defer the fellowship in order to work for the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which led to one of her most powerful bodies of work: a series of photographs of Japanese Americans who were interned in detention camps following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. According to historian Linda Gordon, both the military and the WRA staff censored Lange’s photos of internment camps like the one in Manzanar, California. “US Army Major Beasley actually wrote ‘Impounded’ across some of the prints (luckily, not on the negatives),” Gordon said. The images were suppressed and went unpublished until after the war.

Lange remained active throughout her life, using her photographs to raise awareness of the struggles faced by Americans. In 1955 her work was included in Edward Steichen’s landmark photography exhibition The Family of Man at MoMA, and in the years leading up to her death in 1965, she photographed across the globe, often traveling with Taylor, by then a land reform consultant to the United Nations (the US Agency for International Development) and the Ford Foundation.

While the government used Lange’s photographs for propaganda purposes, she saw her work as a means of advocacy, aiming to assist those in need. Lange’s legacy endures as a testament to the power of visual storytelling in highlighting social injustice and advocating for change. Through her lens, she immortalized the resilience of those weathering the storm of the Great Depression.

In L.A.’s Highland Park, a Tudor Time Capsule Is Available for the First Time in Decades

LeBron James’ Wife Savannah Cheers in Balenciaga With Daughter Zhuri, Jennifer Hudson and Son David Otunga Jr. Pop in Red, and More Star Style at LA Lakers Games Through the Years

If you loved NBC’s ER, this new Max medical drama is the show for you

Orioles Sale to Rubenstein Just the Fifth MLB Deal in 12 Years