Artists’ grant applications tend to be anodyne things because the point of them is often to appeal to an organization’s sensibilities, not to take a stand. But take a stand is what Elizabeth Catlett did in 1945 when she wrote of the “double handicap of race and sex” that Black women like herself faced. “Because of subtle American propaganda in the movies, radio and stage they have come to be generally regarded as good cooks, housemaids and nurses and little else,” Catlett wrote in her Rosenwald Fellowship plan in 1945.

“At this time when we are fighting an all out war against tyranny and oppression,” she continued, “it is extremely important that the picture of Negro women as participants in this fight, throughout the history of America, be sharply drawn.” She referred to the rape of Recy Taylor by six white men the year before; Taylor’s assailants were never indicted.

Catlett’s art rebuts an avalanche of racist, misogynistic images that she frequently encountered, offering pictures of strength, endurance, and proud femininity. Working in sculpture, painting, and printmaking, Catlett took styles associated with European modernism, then applied them to Black women, who were often demeaned or altogether ignored by white male artists abroad. The artist, who started out in the US before achieving fame in Mexico, would go on to produce works referring explicitly to a range of political subjects, from the imprisonment of Angela Davis to the stripping of rights from Indigenous Mexicans.

In doing so, she asked prescient questions, ones that have recently been taken up anew by generations of artists after her: What makes a good form of representation? And can images move people to action, raising political consciousness among the masses?

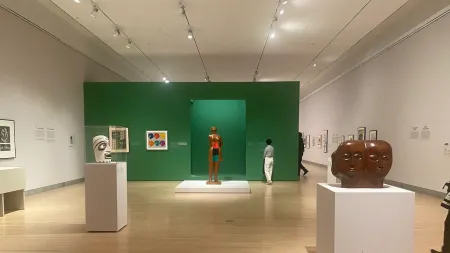

Now, for the first time in nearly 25 years, Catlett is the subject of a proper US retrospective, with some 150 of her works in multiple mediums brought together at the Brooklyn Museum. (After it closes in New York, the exhibition heads next to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which co-organized it, and then to the Art Institute of Chicago.) The exhibition makes a compelling case that Catlett, though hardly overlooked in the history of American modernism, deserves to be viewed as a transnational pioneer and one of the finest 20th-century artists. Below, a look at five essential works by Catlett, each of which appears in the Brooklyn show.

-

Head of a Woman, 1942–44

Image Credit: Alex Greenberger/ARTnews In 1942, with her first husband, Charles White, Catlett moved to New York, where the artist began studying with Ossip Zadkine, a Belarusian-born sculptor of French extraction. Zadkine’s angular sculptures of people were done under the sign of Cubism, a style that fractured the traditional sense of perspective such that objects were rendered as though seen from more than one vantage point. He instilled the precepts of European modernism in Catlett, whose experiences with those in Zadkine’s circle—what the Brooklyn Museum curators term the “white art world”—led her to apply this mode to Black subject matter. Made while Catlett was living in Harlem, this painting takes a Zadkine-like approach to its Black female sitter, pitching one cheek upward, then rendering it as though it had split into a grouping of geometric planes.

-

My reward has been bars between me and the rest of the land, 1946–47

Image Credit: Alex Greenberger/ARTnews In her legendary 1946–47 prints series “The Negro Woman” (which she later retitled “The Black Woman” in 1989), Catlett explored the Black female experience, showing how the past continued to wear on women like her in the present. Catlett has chosen not to represent details of this woman’s milieu in this linocut, rendering the background only as a series of inked gashes. That means that the work, like many others in the series, appears to take place out of time—it could take place centuries ago, when enslaved people labored in captivity, or it could take place in the early part of the 20th century, when sharecropping remained relatively common.

Catlett alludes to violence and exploitation without ever showing it—the razor wire runs across this worker’s throat, threatening to pierce her neck if she moves forward. But the worker wears a defiant expression anyway, looking neither tired nor aggrieved by her circumstances, which are pictured in such a way that they recall labor by enslaved people on plantations. The Brooklyn Museum’s wall text quotes the younger artist Cameron Rowland, speaking on this work: “The only rewards offered by those who have taken her life and labor are the deprivations conferred by the enclosure of anti-Blackness.”

-

Sharecropper, 1952

Image Credit: Alex Greenberger/ARTnews This work, arguably Catlett’s most famous piece, was one she printed more than once—there are three versions in the Brooklyn Museum show, with the 1952 one at center. She printed at Mexico City’s Taller de Gráfica Popular workshop, whose members produced art that was avowedly leftist. Like them, Catlett utilized a realist style, with her work directed not at the art-world elite but the masses. Here, she memorializes a Black female worker, the brim of her hat forming a giant halo. In that way, the work, with its square form, its simplicity, and its closely cropped composition, recalls religious icons of the Medieval era. Catlett seeks to sanctify this sharecropper, a saint for our times.

-

Untitled (Composition for a Peace Poster), ca. 1950

Image Credit: Alex Greenberger/ARTnews Many of the Taller de Gráfica Popular works were produced collaboratively, and the entire workshop is credited for this work, the product of a design by Catlett and a linocut by Alberto Beltrán. The print was meant as a call for an end to war at a time when tensions over nuclear weapons seemed to spell violence for the world more broadly. A giant hand can be seen shielding the people below from a flotilla of pointy bayonets. But even despite all the doomful imagery, the figures beneath remain steadfast—a woman grips her child, hopefully looking outward, while others rush behind her.

Taller de Gráfica Popular expressed specific concern about how the US, a country whose nuclear arsenal was unparalleled at the time, would alter the course of geopolitics. The US government, seeking to quash any who opposed its policies, went on to blacklist its members, including Catlett, who was declared an “undesirable alien.” Catlett characteristically seemed little bothered by this. In 1970, when she spoke at a Black art conference in Illinois by phone, she said, “To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitute a threat to Black people, to that degree and more, do I hope I have earned that honor. For I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be, a Black revolutionary artist, and all that it implies.”

-

Political Prisoner, 1971

Image Credit: Alex Greenberger/ARTnews The rise of the Black Power movement in the late 1960s led Catlett to produce an array of artworks centering its imagery, including this sculpture prominently featuring the colors of the Pan-African flag at its center. The titular prisoner of the piece’s title is Angela Davis, who, in 1970, was arrested on suspicion of murder, only to be acquitted two years later—though not after she had served more than a year in prison first. In allusion to Davis’s detainment, Catlett has bound this figure’s hands in a pair of cuffs, though this is only visible once the viewer looks behind the piece. From the front, however, this figure looks defiant and largely unfazed. The focus, then, is not Davis’s arrest, but her perseverance in spite of it.

Head of a Woman, 1942–44

In 1942, with her first husband, Charles White, Catlett moved to New York, where the artist began studying with Ossip Zadkine, a Belarusian-born sculptor of French extraction. Zadkine’s angular sculptures of people were done under the sign of Cubism, a style that fractured the traditional sense of perspective such that objects were rendered as though seen from more than one vantage point. He instilled the precepts of European modernism in Catlett, whose experiences with those in Zadkine’s circle—what the Brooklyn Museum curators term the “white art world”—led her to apply this mode to Black subject matter. Made while Catlett was living in Harlem, this painting takes a Zadkine-like approach to its Black female sitter, pitching one cheek upward, then rendering it as though it had split into a grouping of geometric planes.

My reward has been bars between me and the rest of the land, 1946–47

In her legendary 1946–47 prints series “The Negro Woman” (which she later retitled “The Black Woman” in 1989), Catlett explored the Black female experience, showing how the past continued to wear on women like her in the present. Catlett has chosen not to represent details of this woman’s milieu in this linocut, rendering the background only as a series of inked gashes. That means that the work, like many others in the series, appears to take place out of time—it could take place centuries ago, when enslaved people labored in captivity, or it could take place in the early part of the 20th century, when sharecropping remained relatively common.

Catlett alludes to violence and exploitation without ever showing it—the razor wire runs across this worker’s throat, threatening to pierce her neck if she moves forward. But the worker wears a defiant expression anyway, looking neither tired nor aggrieved by her circumstances, which are pictured in such a way that they recall labor by enslaved people on plantations. The Brooklyn Museum’s wall text quotes the younger artist Cameron Rowland, speaking on this work: “The only rewards offered by those who have taken her life and labor are the deprivations conferred by the enclosure of anti-Blackness.”

Sharecropper, 1952

This work, arguably Catlett’s most famous piece, was one she printed more than once—there are three versions in the Brooklyn Museum show, with the 1952 one at center. She printed at Mexico City’s Taller de Gráfica Popular workshop, whose members produced art that was avowedly leftist. Like them, Catlett utilized a realist style, with her work directed not at the art-world elite but the masses. Here, she memorializes a Black female worker, the brim of her hat forming a giant halo. In that way, the work, with its square form, its simplicity, and its closely cropped composition, recalls religious icons of the Medieval era. Catlett seeks to sanctify this sharecropper, a saint for our times.

Untitled (Composition for a Peace Poster), ca. 1950

Many of the Taller de Gráfica Popular works were produced collaboratively, and the entire workshop is credited for this work, the product of a design by Catlett and a linocut by Alberto Beltrán. The print was meant as a call for an end to war at a time when tensions over nuclear weapons seemed to spell violence for the world more broadly. A giant hand can be seen shielding the people below from a flotilla of pointy bayonets. But even despite all the doomful imagery, the figures beneath remain steadfast—a woman grips her child, hopefully looking outward, while others rush behind her.

Taller de Gráfica Popular expressed specific concern about how the US, a country whose nuclear arsenal was unparalleled at the time, would alter the course of geopolitics. The US government, seeking to quash any who opposed its policies, went on to blacklist its members, including Catlett, who was declared an “undesirable alien.” Catlett characteristically seemed little bothered by this. In 1970, when she spoke at a Black art conference in Illinois by phone, she said, “To the degree and in the proportion that the United States constitute a threat to Black people, to that degree and more, do I hope I have earned that honor. For I have been, and am currently, and always hope to be, a Black revolutionary artist, and all that it implies.”

Political Prisoner, 1971

The rise of the Black Power movement in the late 1960s led Catlett to produce an array of artworks centering its imagery, including this sculpture prominently featuring the colors of the Pan-African flag at its center. The titular prisoner of the piece’s title is Angela Davis, who, in 1970, was arrested on suspicion of murder, only to be acquitted two years later—though not after she had served more than a year in prison first. In allusion to Davis’s detainment, Catlett has bound this figure’s hands in a pair of cuffs, though this is only visible once the viewer looks behind the piece. From the front, however, this figure looks defiant and largely unfazed. The focus, then, is not Davis’s arrest, but her perseverance in spite of it.

Nicole Scherzinger’s $6.7 Million Home Has Sweeping Views From Downtown L.A. to the Pacific

Melania Trump’s Nude Fashion Shoot: Photographer Gives His Point of View

Researchers found a simple way to make concrete 560% stronger

Relevent to Manage Bundesliga Media Rights in the Americas