Nothing haunts art researchers like the paintings, sculptures, and prints that they can’t track down—whether for a catalogue raisonné, an artist’s archive, or a scholarly article. This is felt even more acutely by those with a sentimental connection to an artwork that has disappeared into a private collection or changed hands without leaving a paper trail.

Such was the case with a portrait of modernist artist Anna Walinska, painted by her close friend Arshile Gorky. The Arshile Gorky Foundation was hoping to track down the oil on canvas for a catalogue raisonné, and Rosina Rubin, Walinska’s niece and founder of Atelier Anna Walinska, wanted to find out what happened to this painting, which she remembered hanging in the entryway of her family’s apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

I heard about the search through the Atelier Anna Walinska newsletter, reached out to Rubin and the Gorky Foundation, and wrote an article that we hoped would cause this never-exhibited painting to resurface. For two years there was no response . . . until there was. A neighbor of the private collector who owns the painting saw the article, recognized the portrait, and said something. A happy reunion ensued.

Artworks are never really lost, of course, unless they’re destroyed. They do wander, though (and occasionally do get stolen), thus distancing themselves from those that know their stories most fully. Here are 10 such pieces, long separated from people hoping to study them. Have you seen these artworks?

-

Eva Gonzalès, Les Oies (c. 1865–70)

Image Credit: Courtesy of the Wildenstein Plattner Institute. Two years after French Impressionist Eva Gonzalès died in childbirth, her family and Léon Leenhoff (stepson of Édouard Manet) organized an 1885 retrospective for her that included 88 oil paintings, pastels, drawings, and engravings. A brief catalogue was printed for the occasion; it was unillustrated, but thanks to three installation photographs, researchers have been able to firmly piece together the exhibited Gonzalès works—including a small, square-format oil painting titled Les Oies. This petite canvas of a flock of geese painted early in her career is unusual, since she usually painted portraits and still lifes, and it’s unclear whether Gonzalès had, at the time of its creation, already started studying under Manet (as the only student he ever formally took on). We do know that it was connected to Manet in some way, since it was loaned to the 1885 retrospective from the collection of Suzanne Manet, the artist’s widow. The only other public appearance of this flock was at a November 1958 auction at the Salons du Trianon-Palace in Versailles, after which it presumably entered a private collection.

If you have any leads on the whereabouts of this work, please contact the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, which is working on a reviewed edition of the 1990 Gonzalès catalogue raisonné together with one of its original authors, Marie-Caroline Sainsaulieu.

Courtesy of the Wildenstein Plattner Institute. -

Josef Albers, Self-portrait (c. 1917–1919)

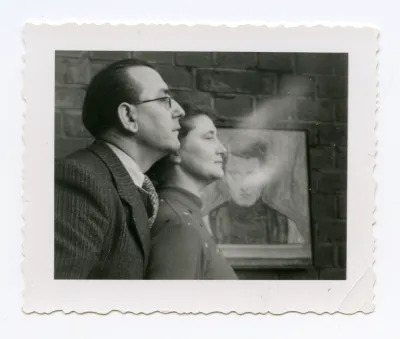

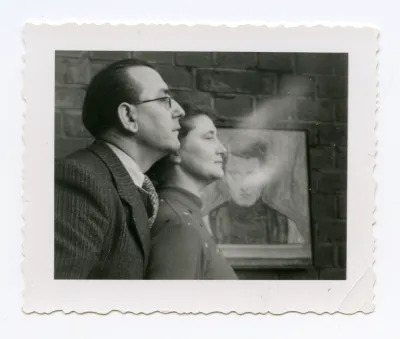

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image courtesy of the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation. Josef Albers was an aspiring artist working a day job as a small-town elementary school teacher in Westphalia, Germany, when he painted this self-portrait, years before he ever made a homage to the square (now his best-known subject). Predating his time at the Bauhaus and his hard-edged geometric abstractions, this expressive early work is one of several paintings from the beginning of Albers’s career whose whereabouts are unknown (some of which he may have destroyed or painted over). This painting is known only from a circa 1948 snapshot taken at an exhibition somewhere in Westphalia, and the fact that it survived World War II suggests that it likely still exists somewhere today, possibly in a private collection. Albers depicts himself in romantic garb, with swirling background lines that may reflect his admiration of artists such as Edvard Munch and Ferdinand Hodler at the time. The couple in the photo’s foreground are the artist’s sister, Elisabeth, and her husband, Rudolf Marx.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation.

-

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait de Jeune Fille (1918–19)

Image Credit: Alberto G. D’Atri papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Photograph of archival print taken by Leslie Koot. It has been more than a century since this portrait in Amedeo Modigliani’s signature modernist style was last publicly seen, in 1922, just two years after his death. It was then being sold at the Parisian Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, which had acquired Portrait de Jeune Fille from the collection of American-French painter Charles Hall Thorndike (who owned at least one other Modigliani work and may have met the artist in southern France). Painted on a French standard-size Marine 8 canvas, the painting reflects Modigliani’s habit of using canvas dimensions designated for seascapes, which he felt best accommodated his elongated portraits. The work is known only from a black-and-white photograph taken by the gallery, which it reproduced in a 2015 book cataloguing every Modigliani work it sold. It is likely a portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne—the artist’s lover, mother of his daughter, and his most frequent model, whom he painted more than 25 times. Compared with Modigliani’s other portraits of Jeanne, there is a slight swelling of the face here, which helps date the painting to around 1918, when she was nearing the end of her first pregnancy. Portrait de Jeune Fille isn’t included in Ambrogio Ceroni’s 1970 catalogue of Modigliani’s work, the most widely accepted Modigliani catalogue raisonné. This might be explained by an early sale of the work and its possible departure from France soon after.

If you have information about this portrait, please contact the scholars at the Modigliani Initiative, who are eager to see the work in color and study it in collaboration with other scholars.

-

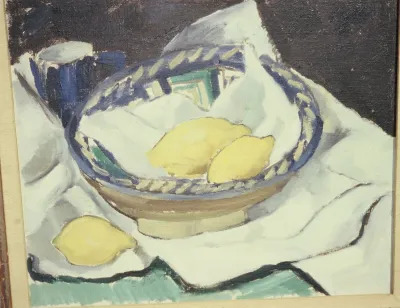

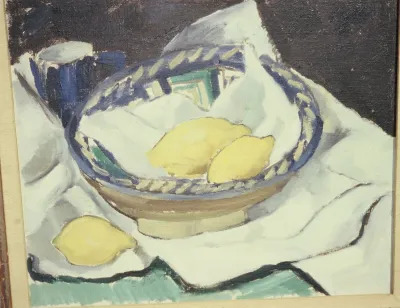

Marsden Hartley, Lemons in a Bowl (1927–29)

Image Credit: Courtesy of the Marsden Hartley Legacy Project, Bates College Museum of Art. Of the many places where modernist painter and printmaker Marsden Hartley traveled and worked worldwide—Maine, Berlin, New York, Sante Fe, and Bermuda (among others)—it was while in Provence in the late 1920s that he painted this still life of lemons in a bowl. Hartley’s style changed direction several times, including experimentation with expressive landscapes and geometric paintings that fused Cubism and colorful symbols. Here, the artist was looking closely at the work of Paul Cézanne (himself active in Provence) and exploring the possibilities of the still life. (Hartley painted Mont Sainte-Victoire, Cézanne’s beloved subject, around the same time.) The artist gave Lemons in a Bowl to a Madame J. Tessier in France, and it remained in her family until it was acquired by a New York collection in the early 1950s. The last known location of the work was in the collection of Saul and Ethel Brodsky in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, but its present whereabouts are unknown.

If you have any information about this still life, please contact the Marsden Hartley Legacy Project at the Bates College Museum of Art in Hartley’s birthplace, Lewiston, Maine.

-

Isamu Noguchi, Power House (Study for Neon Tube Sculpture) (1928)

Image Credit: Artwork © Estate of Isamu Noguchi/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image courtesy of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation. A 24-year-old Isamu Noguchi was living near Paris on an extended Guggenheim Fellowship in 1928, experimenting with kinetic sculpture and materials such as stone, wood, bent metal, and neon tubing. One of the works he made that year was Power House, also referred to as Study for Neon Tube Sculpture since it was likely a model for another, unrealized work. Neon tubes were a relatively new invention at the time, unveiled to the public in 1910, and their use in sculpture was considered avant garde. At his studio at 11 Rue Dedouvre in the Paris suburb of Gentilly, Noguchi created a few works related to lighting that testify to the artist’s interest in incorporating light into sculptures and anticipate his 1950s Akari light sculptures. Power House was last known to be in a storage unit that Noguchi set up when he left the city in February 1929, kept in a specially built crate together with other artworks and some of Noguchi’s tools. When the artist returned to Paris a few years later he found that the crate had been either destroyed or thrown away, possibly because he wasn’t making payments on the unit during those early years of the Depression. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation is still hopeful that someone recognized the artistic value of these works, rescued them, and then kept or sold them.

If you have any information about Power House, please contact the Isamu Noguchi Foundation.

-

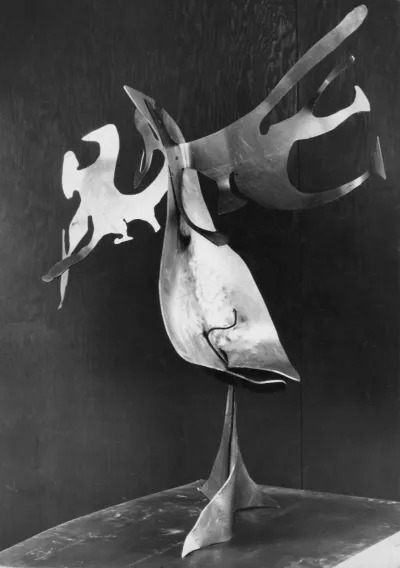

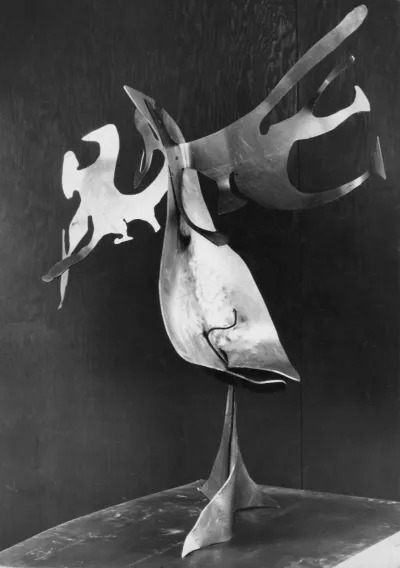

Ibram Lassaw, Abstract Sculpture in Steel (1938)

Image Credit: Courtesy of Denise Lassaw. There’s a 1938 sister sculpture of this steel abstraction held by the Whitney Museum of American Art, but this piece—made the same year and roughly double in size—is missing. Abstract Sculpture in Steel was created by Russian-American sculptor Ibram Lassaw during the years he worked for the Works Progress Administration, where he sometimes made sculptures and sometimes cleaned pigeon droppings off New York City public statues (along with Jackson Pollock and others). Sculptures and paintings commissioned by the WPA were intended to adorn public buildings, but this work has disappeared without a trace beyond this slide of a photograph by the artist. The sculpture was made using a technique Lassaw was exploring: Together with artist Gertrude Greene, he welded sheet metal using a small agricultural forge ordered from a Sears Roebuck catalogue. It was ultimately too hard to make complex shapes this way, and after two sculptures Lassaw gave up the technique.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the artist’s daughter, Denise Lassaw, via the Berry Campbell Gallery.

-

Philip Guston, AT-6’s Over Matagorda Bay (1943)

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © The Estate of Philip Guston. Digital image courtesy of The Estate of Philip Guston. After working on large murals for a few years, American artist Philip Guston was shifting to easel painting in the early 1940s when he was commissioned to create a series of 24 gouaches to illustrate an article in Fortune magazine. The article published in the magazine’s February 1944 issue, titled The Air Training Program, covered the swift creation of a formidable American air force during World War II. One of Guston’s gouaches from the series, AT-6’s Over Matagorda Bay (possibly also called Flight Formation), shows seven North American AT-6 planes soaring over the bay on the Texas Gulf Coast in a practice mission. The AT-6 was an aircraft used to train air force pilots as of World War II until the 1970s, and Guston’s painting provides different views of these impressive machines. Seen from ground level, the aircraft occupy the upper half of the composition, but it’s the odd collection of driftwood and metal scraps on the shore below, in the foreground, that steal the show. The painting was exhibited twice, once at the Iowa Memorial Union in 1944 and again at the Woodstock Artists Association in 1997, but it hasn’t been seen since.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Philip Guston Foundation.

-

Dorothea Tanning, Tempest in White (1947)

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © The Estate of Dorothea Tanning/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. DIgital image courtesy of the Dorothea Tanning Foundation. “I think it is one of my best pictures,” Dorothea Tanning wrote about Tempest in White in a September 1947 letter to art dealer Julien Levy. Levy was planning to offer paintings to organizers of an upcoming exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, and Tanning thought it might be a good fit. “The colors are blue-whites, mauve, brown, black, and a heavy spot of dark orange (the hair),” Tanning wrote to Levy. While Tempest in White wasn’t shown in Chicago, it was exhibited at Tanning’s second solo show at Julien Levy Gallery in New York in January 1948, and later that year it appeared in the 1948 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Paintingat the Whitney Museum of American Art. The last time it was publicly shown was at a 1949 solo exhibition at the American Contemporary Gallery in Hollywood. It was possibly sold to a private collector in Hollywood at that time, or Levy may have found a buyer. Tanning listed the painting as “lost” in her personal inventory (as opposed to “destroyed” or “stolen,” which is how she marked other works in her inventory).

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, which is trying to locate several works for inclusion in a catalogue raisonné. To view additional Tanning works whose whereabouts are unknown, see the bottom of the foundation’s home page.

-

Roy Lichtenstein, Knight with Lance on Horse (c. 1948)

Image Credit: Artwork © copyright Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Digital image courtesy of the Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. Roy Lichtenstein’s BFA studies at Ohio State University were interrupted when he was drafted into the army in 1943. When he returned from the war in 1946 he went back to Ohio State, where he completed his studies and went on to get his master’s degree in fine arts. This abstracted and Picassoesque pastel, titled Knight with Lance on Horse, was part of Lichtenstein’s 1949 MFA thesis exhibition and was reproduced in his printed thesis along with other works. (Around this time Lichtenstein was inspired by the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered work about the Norman conquest of England that is full of equestrian knights.) After being shown at Lichtenstein’s thesis exhibition, the drawing entered a private collection in Ohio, either as a purchase or as a gift from the artist; eventually it made its way into a Miami private collection and may have been considered for sale by a local auction house. All efforts to locate the owner or heirs have been unsuccessful.

If you’ve seen this knight, please contact the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation; other unlocated works are listed on the artist’s catalogue raisonné website.

-

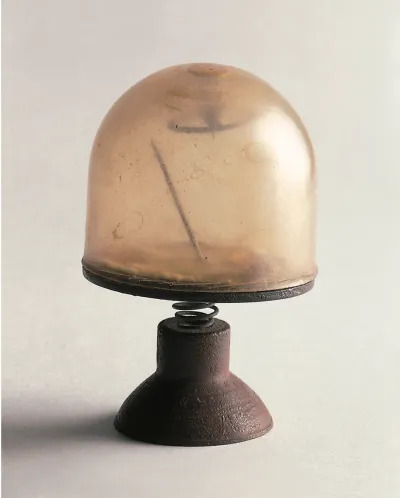

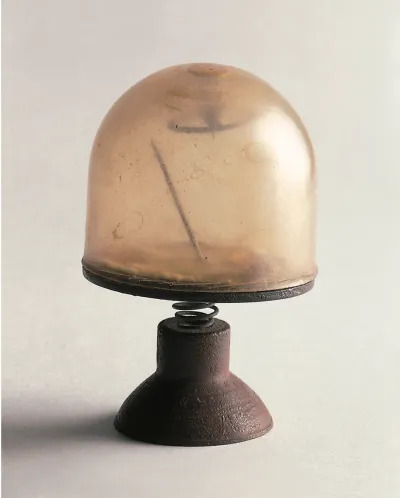

Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Scatole Personali) (1953)

Image Credit: Artwork copyright © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Digital image courtesy of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. Many of the unsold works from Robert Rauschenberg’s first European exhibition, at the Galleria L’Obelisco in Rome in March 1953, ended up in Florence’s Arno River. (Rauschenberg tossed them in there himself, as a gesture suggested by a sardonic reviewer, the art historian Carlo Volpe.) This, thankfully, wasn’t one of them, although scholars have lost track of its whereabouts. Just a few years after studying under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, a 27-year-old Rauschenberg spent eight months touring Morocco and Italy with his lover at the time, fellow artist Cy Twombly. He started making assemblages called feticci personali (personal fetishes) and scatole personali (personal boxes) on that trip, including this one made with a rubber suction cup and sewing needle (among other odd collected objects). Works such as this led to the evolution of Rauschenberg’s celebrated Combines, which he started creating in 1954 upon his return to New York. Untitled (Scatole Personali) was acquired by Galleria L’Obelisco co-owner Gaspero del Corso, who kept it until his death in 1997. Exhibited that year at a Rauschenberg retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, it then went into the collection of distant relatives of Del Corso and has disappeared since.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

Eva Gonzalès, Les Oies (c. 1865–70)

Two years after French Impressionist Eva Gonzalès died in childbirth, her family and Léon Leenhoff (stepson of Édouard Manet) organized an 1885 retrospective for her that included 88 oil paintings, pastels, drawings, and engravings. A brief catalogue was printed for the occasion; it was unillustrated, but thanks to three installation photographs, researchers have been able to firmly piece together the exhibited Gonzalès works—including a small, square-format oil painting titled Les Oies. This petite canvas of a flock of geese painted early in her career is unusual, since she usually painted portraits and still lifes, and it’s unclear whether Gonzalès had, at the time of its creation, already started studying under Manet (as the only student he ever formally took on). We do know that it was connected to Manet in some way, since it was loaned to the 1885 retrospective from the collection of Suzanne Manet, the artist’s widow. The only other public appearance of this flock was at a November 1958 auction at the Salons du Trianon-Palace in Versailles, after which it presumably entered a private collection.

If you have any leads on the whereabouts of this work, please contact the Wildenstein Plattner Institute, which is working on a reviewed edition of the 1990 Gonzalès catalogue raisonné together with one of its original authors, Marie-Caroline Sainsaulieu.

Josef Albers, Self-portrait (c. 1917–1919)

Josef Albers was an aspiring artist working a day job as a small-town elementary school teacher in Westphalia, Germany, when he painted this self-portrait, years before he ever made a homage to the square (now his best-known subject). Predating his time at the Bauhaus and his hard-edged geometric abstractions, this expressive early work is one of several paintings from the beginning of Albers’s career whose whereabouts are unknown (some of which he may have destroyed or painted over). This painting is known only from a circa 1948 snapshot taken at an exhibition somewhere in Westphalia, and the fact that it survived World War II suggests that it likely still exists somewhere today, possibly in a private collection. Albers depicts himself in romantic garb, with swirling background lines that may reflect his admiration of artists such as Edvard Munch and Ferdinand Hodler at the time. The couple in the photo’s foreground are the artist’s sister, Elisabeth, and her husband, Rudolf Marx.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation.

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait de Jeune Fille (1918–19)

It has been more than a century since this portrait in Amedeo Modigliani’s signature modernist style was last publicly seen, in 1922, just two years after his death. It was then being sold at the Parisian Galerie Bernheim-Jeune, which had acquired Portrait de Jeune Fille from the collection of American-French painter Charles Hall Thorndike (who owned at least one other Modigliani work and may have met the artist in southern France). Painted on a French standard-size Marine 8 canvas, the painting reflects Modigliani’s habit of using canvas dimensions designated for seascapes, which he felt best accommodated his elongated portraits. The work is known only from a black-and-white photograph taken by the gallery, which it reproduced in a 2015 book cataloguing every Modigliani work it sold. It is likely a portrait of Jeanne Hébuterne—the artist’s lover, mother of his daughter, and his most frequent model, whom he painted more than 25 times. Compared with Modigliani’s other portraits of Jeanne, there is a slight swelling of the face here, which helps date the painting to around 1918, when she was nearing the end of her first pregnancy. Portrait de Jeune Fille isn’t included in Ambrogio Ceroni’s 1970 catalogue of Modigliani’s work, the most widely accepted Modigliani catalogue raisonné. This might be explained by an early sale of the work and its possible departure from France soon after.

If you have information about this portrait, please contact the scholars at the Modigliani Initiative, who are eager to see the work in color and study it in collaboration with other scholars.

Marsden Hartley, Lemons in a Bowl (1927–29)

Of the many places where modernist painter and printmaker Marsden Hartley traveled and worked worldwide—Maine, Berlin, New York, Sante Fe, and Bermuda (among others)—it was while in Provence in the late 1920s that he painted this still life of lemons in a bowl. Hartley’s style changed direction several times, including experimentation with expressive landscapes and geometric paintings that fused Cubism and colorful symbols. Here, the artist was looking closely at the work of Paul Cézanne (himself active in Provence) and exploring the possibilities of the still life. (Hartley painted Mont Sainte-Victoire, Cézanne’s beloved subject, around the same time.) The artist gave Lemons in a Bowl to a Madame J. Tessier in France, and it remained in her family until it was acquired by a New York collection in the early 1950s. The last known location of the work was in the collection of Saul and Ethel Brodsky in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, but its present whereabouts are unknown.

If you have any information about this still life, please contact the Marsden Hartley Legacy Project at the Bates College Museum of Art in Hartley’s birthplace, Lewiston, Maine.

Isamu Noguchi, Power House (Study for Neon Tube Sculpture) (1928)

A 24-year-old Isamu Noguchi was living near Paris on an extended Guggenheim Fellowship in 1928, experimenting with kinetic sculpture and materials such as stone, wood, bent metal, and neon tubing. One of the works he made that year was Power House, also referred to as Study for Neon Tube Sculpture since it was likely a model for another, unrealized work. Neon tubes were a relatively new invention at the time, unveiled to the public in 1910, and their use in sculpture was considered avant garde. At his studio at 11 Rue Dedouvre in the Paris suburb of Gentilly, Noguchi created a few works related to lighting that testify to the artist’s interest in incorporating light into sculptures and anticipate his 1950s Akari light sculptures. Power House was last known to be in a storage unit that Noguchi set up when he left the city in February 1929, kept in a specially built crate together with other artworks and some of Noguchi’s tools. When the artist returned to Paris a few years later he found that the crate had been either destroyed or thrown away, possibly because he wasn’t making payments on the unit during those early years of the Depression. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation is still hopeful that someone recognized the artistic value of these works, rescued them, and then kept or sold them.

If you have any information about Power House, please contact the Isamu Noguchi Foundation.

Ibram Lassaw, Abstract Sculpture in Steel (1938)

There’s a 1938 sister sculpture of this steel abstraction held by the Whitney Museum of American Art, but this piece—made the same year and roughly double in size—is missing. Abstract Sculpture in Steel was created by Russian-American sculptor Ibram Lassaw during the years he worked for the Works Progress Administration, where he sometimes made sculptures and sometimes cleaned pigeon droppings off New York City public statues (along with Jackson Pollock and others). Sculptures and paintings commissioned by the WPA were intended to adorn public buildings, but this work has disappeared without a trace beyond this slide of a photograph by the artist. The sculpture was made using a technique Lassaw was exploring: Together with artist Gertrude Greene, he welded sheet metal using a small agricultural forge ordered from a Sears Roebuck catalogue. It was ultimately too hard to make complex shapes this way, and after two sculptures Lassaw gave up the technique.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the artist’s daughter, Denise Lassaw, via the Berry Campbell Gallery.

Philip Guston, AT-6’s Over Matagorda Bay (1943)

After working on large murals for a few years, American artist Philip Guston was shifting to easel painting in the early 1940s when he was commissioned to create a series of 24 gouaches to illustrate an article in Fortune magazine. The article published in the magazine’s February 1944 issue, titled The Air Training Program, covered the swift creation of a formidable American air force during World War II. One of Guston’s gouaches from the series, AT-6’s Over Matagorda Bay (possibly also called Flight Formation), shows seven North American AT-6 planes soaring over the bay on the Texas Gulf Coast in a practice mission. The AT-6 was an aircraft used to train air force pilots as of World War II until the 1970s, and Guston’s painting provides different views of these impressive machines. Seen from ground level, the aircraft occupy the upper half of the composition, but it’s the odd collection of driftwood and metal scraps on the shore below, in the foreground, that steal the show. The painting was exhibited twice, once at the Iowa Memorial Union in 1944 and again at the Woodstock Artists Association in 1997, but it hasn’t been seen since.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Philip Guston Foundation.

Dorothea Tanning, Tempest in White (1947)

“I think it is one of my best pictures,” Dorothea Tanning wrote about Tempest in White in a September 1947 letter to art dealer Julien Levy. Levy was planning to offer paintings to organizers of an upcoming exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, and Tanning thought it might be a good fit. “The colors are blue-whites, mauve, brown, black, and a heavy spot of dark orange (the hair),” Tanning wrote to Levy. While Tempest in White wasn’t shown in Chicago, it was exhibited at Tanning’s second solo show at Julien Levy Gallery in New York in January 1948, and later that year it appeared in the 1948 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Paintingat the Whitney Museum of American Art. The last time it was publicly shown was at a 1949 solo exhibition at the American Contemporary Gallery in Hollywood. It was possibly sold to a private collector in Hollywood at that time, or Levy may have found a buyer. Tanning listed the painting as “lost” in her personal inventory (as opposed to “destroyed” or “stolen,” which is how she marked other works in her inventory).

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Dorothea Tanning Foundation, which is trying to locate several works for inclusion in a catalogue raisonné. To view additional Tanning works whose whereabouts are unknown, see the bottom of the foundation’s home page.

Roy Lichtenstein, Knight with Lance on Horse (c. 1948)

Roy Lichtenstein’s BFA studies at Ohio State University were interrupted when he was drafted into the army in 1943. When he returned from the war in 1946 he went back to Ohio State, where he completed his studies and went on to get his master’s degree in fine arts. This abstracted and Picassoesque pastel, titled Knight with Lance on Horse, was part of Lichtenstein’s 1949 MFA thesis exhibition and was reproduced in his printed thesis along with other works. (Around this time Lichtenstein was inspired by the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered work about the Norman conquest of England that is full of equestrian knights.) After being shown at Lichtenstein’s thesis exhibition, the drawing entered a private collection in Ohio, either as a purchase or as a gift from the artist; eventually it made its way into a Miami private collection and may have been considered for sale by a local auction house. All efforts to locate the owner or heirs have been unsuccessful.

If you’ve seen this knight, please contact the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation; other unlocated works are listed on the artist’s catalogue raisonné website.

Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Scatole Personali) (1953)

Many of the unsold works from Robert Rauschenberg’s first European exhibition, at the Galleria L’Obelisco in Rome in March 1953, ended up in Florence’s Arno River. (Rauschenberg tossed them in there himself, as a gesture suggested by a sardonic reviewer, the art historian Carlo Volpe.) This, thankfully, wasn’t one of them, although scholars have lost track of its whereabouts. Just a few years after studying under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College, a 27-year-old Rauschenberg spent eight months touring Morocco and Italy with his lover at the time, fellow artist Cy Twombly. He started making assemblages called feticci personali (personal fetishes) and scatole personali (personal boxes) on that trip, including this one made with a rubber suction cup and sewing needle (among other odd collected objects). Works such as this led to the evolution of Rauschenberg’s celebrated Combines, which he started creating in 1954 upon his return to New York. Untitled (Scatole Personali) was acquired by Galleria L’Obelisco co-owner Gaspero del Corso, who kept it until his death in 1997. Exhibited that year at a Rauschenberg retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, it then went into the collection of distant relatives of Del Corso and has disappeared since.

If you have any information about this work, please contact the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.

This Speedy 75-Foot Motoryacht Has a Fold-Down Stern That Drops Right Into the Sea

WWD Voices Podcast: Listen to Those That Matter

Today’s deals: $849 M3 MacBook Air, $498 Samsung 55-inch smart TV, $30 Blink Video Doorbell, more

PFL Signs Dubai Deal for Multiple MMA Fights in United Arab Emirates