Jaime Muñoz is a keen cultural observer. A conversation with him veers from art history, the commercialization of contemporary art, and Mesoamerican symbology to Los Angeles car culture, science fiction, and literature.

All of these references and more filter their way into Muñoz’s art, which is steeped with the ethics of hard work and the visual allures of both painting and graphic design. With the precision of an architect who maps out his canvases in Adobe Illustrator, Muñoz uses non-traditional painting techniques, like velvet flocking, airbrushing, vinyl plotting, alongside the manual labor of hand painting and drawing to create vibrant works that are rich in iconography and often overlaid with grid-like patterns and appliqués.

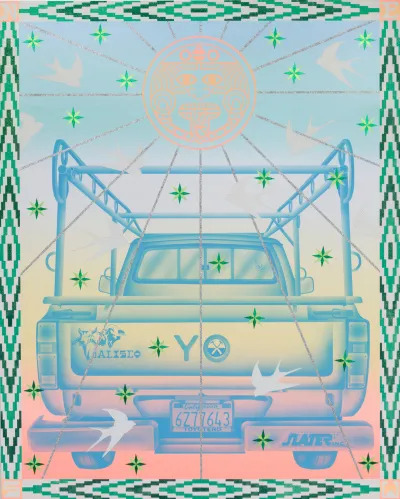

His “Toyoteria” series (2018–20), the first works he created after receiving his BFA, elevates the working man’s truck and his tools paired with observations from his own commutes along LA’s labyrinthine freeway system. In LA Commute (2019), Munoz presents the back of one such truck, in a light airbrushed cyan; the car’s logo has been shortened to just “YO” accompanied by a sticker for the Mexican state of Jalisco with two cows. Above the truck floats a symbol for the Mexica sun deity Tonatiuh.

This series reflects not only Muñoz’s personal experience working with his brother on their own vintage Toyota trucks, but also a particular style vaunted by working-class Latinos in Southern California. “From an artistic perspective, these mini trucks are aesthetically pleasing,” he said. “I look at them like avatars, place holders that represent an aspect of a whole demographic of the working person’s car culture that’s the opposite of other car cultures like low riders and muscle cars that are very polished and refined.”

Even though Muñoz gravitates toward imagery and iconography with personal resonance, his work is driven more by intuition than narrative. “I work with techniques that are very familiar to me,” he said. “Oftentimes I incorporate industrial processes, using the computer to create composition, the vinyl blotter and airbrushing, that comes from my background in graphic design but also in manual labor. It’s a very utilitarian way of working.”

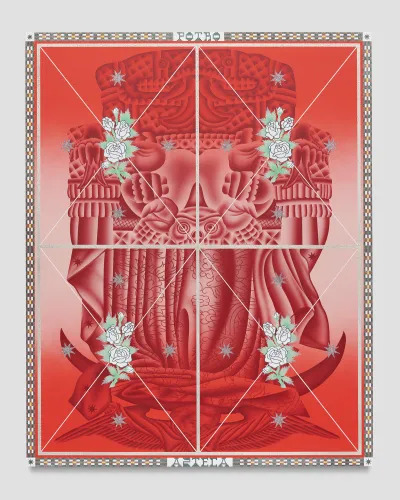

Another series, “Blood Memory” (2019–21), mixes Aztec and Catholic imagery to examine the legacies of colonial history and oppression while acknowledging the cultural heritage and customs that live on through ancestral DNA. Madre (2019), for example, combines the top half of a sculpture of Tonantzín, the Mexica (Aztec) earth goddess, with the bottom half of the iconic depiction of the La Virgen de Guadalupe, standing on a cloud supported by an angel. Using a pop art palette of pink with a hypnotic depth of field and symmetry, Muñoz comments on how the colonization of Mexico by the Spanish subsumed the worship of Tonantzín into devotion to the Virgen as part of their efforts to Christianize the New World.

“Jaime is a philosopher and a thinker. There’s an impeccable, meticulous quality that shows his admiration for fine craft,” said curator Karen Crews Hendon, who organized Muñoz’s current survey at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes in Los Angeles.

A first-generation Chicano born in Los Angeles who grew up in Fontana and Pomona, Muñoz initially planned to pursue graphic design as a practical way to satiate his interest in visual art. While attending school, Muñoz worked physically demanding jobs, as a structural concrete laborer and a gig worker in warehouses, that didn’t offer stability and often necessitated long commutes. But the work kept him afloat financially and eventually he earned an associate degree from Chaffey College. “I was a Sunday painter,” he said of that period of his life. But the guiding force was always an interest “in painting, in the surfaces, the materials.”

His graphic design teacher at Chaffey, artist Mitchell Syrop, encouraged Muñoz to pursue a degree in fine art instead of finding a job in graphic design. Muñoz received his BFA from UCLA’s School of Arts and Architecture, studying with the likes of Lari Pittman, Alma López, Jennifer Bolande, and Patty Wickman.

At UCLA, Muñoz began to experiment with augmenting the flat surfaces of conventional painting, taking a more three-dimensional construction approach. “I felt I could amplify the aesthetic, a discovery that kind of hid my hand in the work,” he said. “As I was trying to resolve painting compositions that led me in the direction of incorporating other materials to create depth in the work, to disrupt the flatness of it as well, and to satisfy my interest in elevating craft materials because craft is another important aesthetic aspect of my work.”

But there’s a dense, formality to Muñoz’s paintings that speaks to his penchant for the Baroque. “I think a lot about Latin American baroque painting especially when I’m responding to religious themes and recontextualizing something about colonial history,” he said. “Looking at that work, I’m trying to create my own contemporary version.”

Muñoz is a part of a cohort of LA-based Chicanx artists whose star has been rising over the past few years. In early 2024, he was included in a major exhibition at Jeffrey Deitch’s Los Angeles gallery, “At the Edge of the Sun,” that featured Muñoz’s art alongside 11 others in his artistic community, including rafa esparza, Guadalupe Rosales, Mario Ayala, and Shizu Saldamando.

“I do feel like we’re in a time like a Harlem Renaissance with all the interest in Latinx and Black art. I don’t know how long that’s going to last, but sometimes I do feel optimistic,” Muñoz said. But he’s quick to point out that his work, along with those of his contemporaries, shouldn’t be pigeonholed based on their identities as has happened throughout the history of contemporary art.

“I see my work as American painting. I’m trying to represent the complexity of the whole country just like any other artist,” he said of his practice that aims to represent the often-unseen narratives of his own experience and those in his community through the exploration of themes of colonialism, immigration, and the commodification of labor.

In mounting “At the Edge of the Sun,” Deitch handed over the power to the exhibiting artists, allowing them to curate the show themselves. Of Muñoz’s work, Deitch told ARTnews, “Jaime’s a masterful, superb painter who uses traditional and industrial techniques, making him part of the fine art tradition but the imagery is also very much from his community in Los Angeles. His work also has a lot of precedence. I see his appropriation of images similar to artists like Sigmar Polke and David Salle, as well Pop Art in general.”

Artist Rubén Ortiz Torres, who is working on a survey of Chicanx art for Mexico City’s Palacio de Belles Artes in 2026, said he thinks Muñoz is one of the city’s most interesting painters working in Los Angeles today. “Jaime’s work is ultra baroque, his colors are exuberant and seductive and he’s making conceptual, connections about Los Angeles and Latin America,” he said. “By playing with pattern and decoration, he creates contemporary codices, that are also codices of the city.”

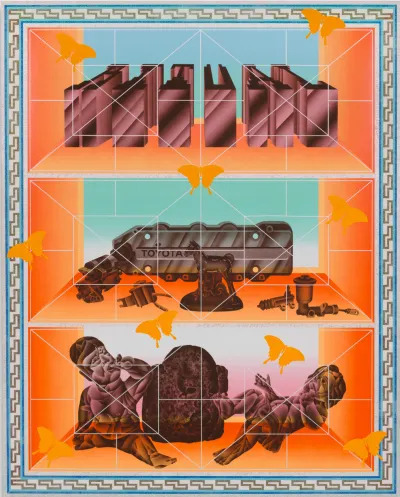

On an afternoon this past September at La Plaza, Muñoz pointed to a 2024 painting Truth Is A Moving Target as an amalgamation of personal references: a truck stop called Loves, lettered in glitter at the top of the canvas; the familiar packaging of the popular Mexican laundry soap Zote; and butterflies, birds, and flora floating about, giving the spirited tableaux a hint of magical realism. “I was looking at a lot of [Henri] Rousseau paintings and wanted to make like a wild kind of scene,” Muñoz said of the painting that lent its name to title of the La Plaza exhibition.

The idea of subjective truth is a key theme in much of Muñoz’s work. He’s wary of didactic meanings, or manifestos “especially about the labor dialogs,” he said. “I want my audience to remember to feel the art. I want to inspire the viewer to look deeply at the work and pull things for themselves, you know, find their own truth because that’s the beauty of art.”

Artist Jesse Krimes Lets His Materials Take Center Stage

For His Current Mid-Career Survey, Vincent Valdez Reflects on 25 Years of Putting America on Trial

How to Make a French 75, the Gin Cocktail That’s Even Better With Real Champagne

Model Dayle Haddon Dies in Pennsylvania

I wish I knew this before I bought a pair of AirPods 4

Hall of Fame Resort’s Football Destination Dreams Wither Away