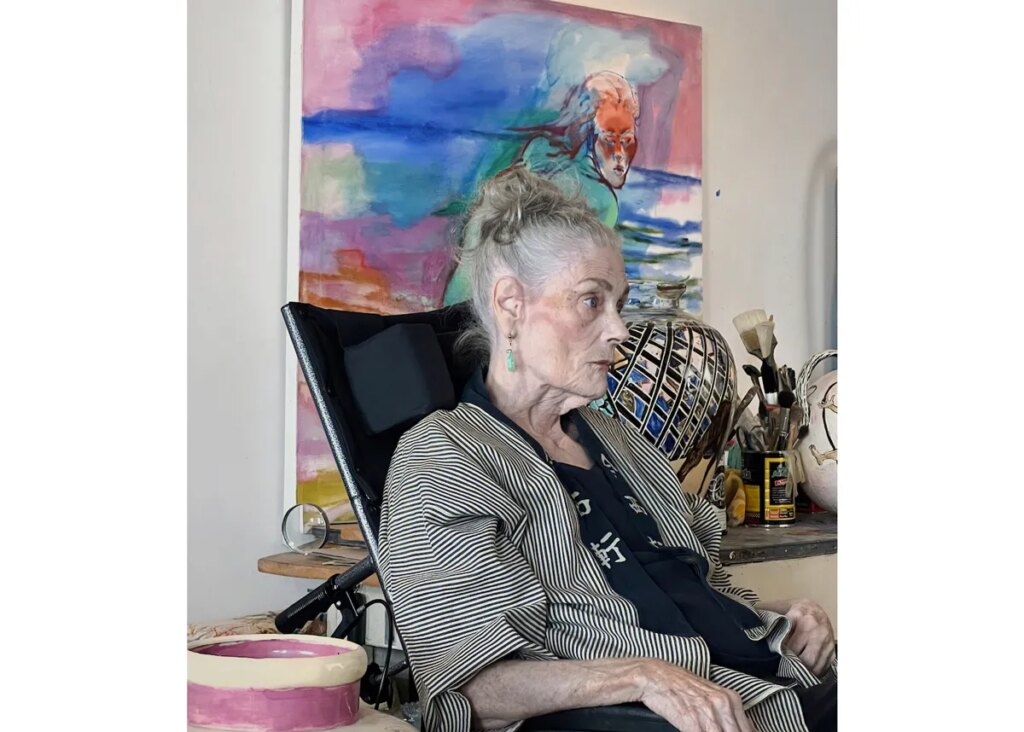

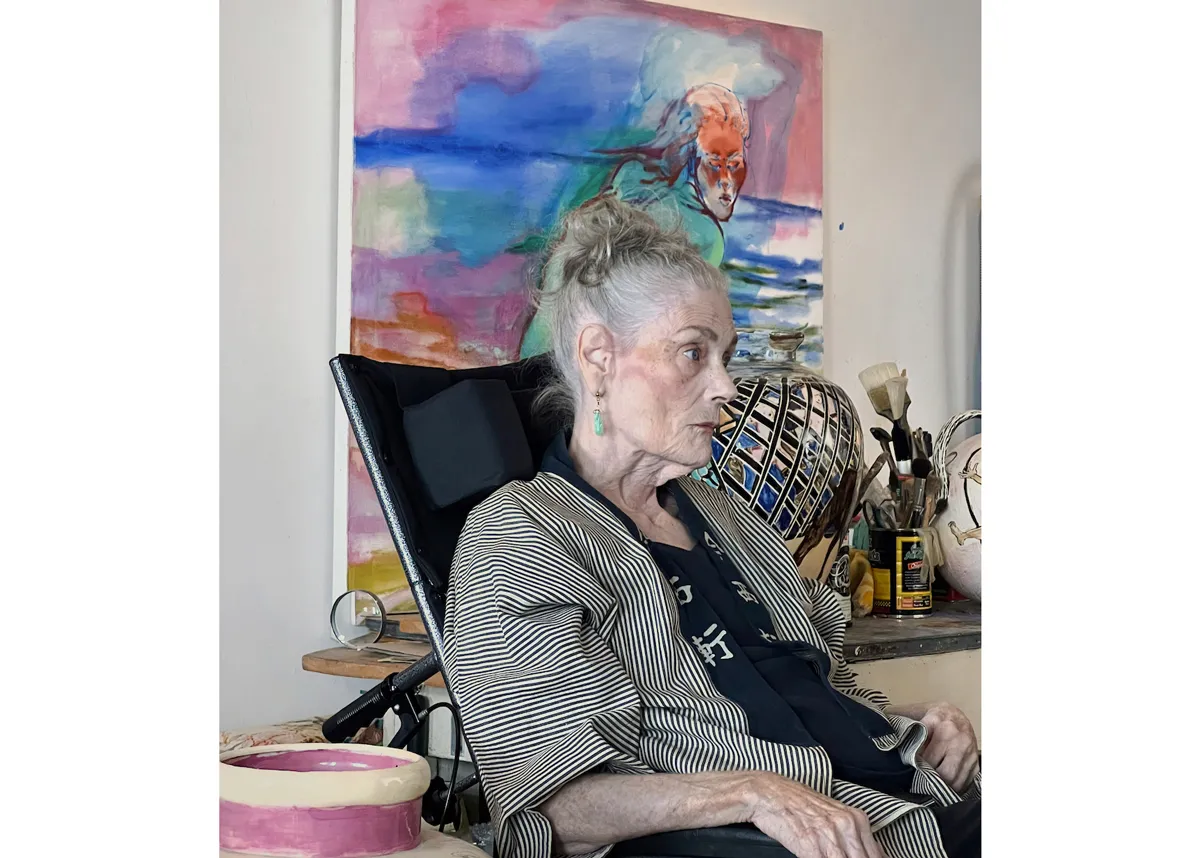

Juanita McNeely, a groundbreaking feminist artist whose work has seen a resurgence in interest over the past few years, died on October 18 in New York. She was 87 years old.

“For over six decades, McNeely addressed themes of bodily sovereignty, liberation, pain and resilience through her work,” James Fuentes, the New York gallery that has represented her since 2020, said in a statement. “McNeely used her art to convey the extreme physicality and movement of the human figure, informed by her personal observations and experiences of sexism, abortion and infirmity.”

In 1967, six years prior to the passage of Roe v. Wade, McNeely moved to New York. During her first year of college, she was diagnosed with cancer and given months to live, but she ultimately survived. Upon her arrival in New York, she became sick again, and also became pregnant. Because abortion was illegal at the time, almost no doctor would operate on her to remove the tumor.

“Nothing was helping me, and nothing would end my misery because the law said you cannot have an abortion,” McNeely said in a 2023 video interview with the Whitney Museum, more than 50 years later and months after the Supreme Court overturned Roe with its 2022 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

As artist and art historian Sharyn M. Finnegan recounts in a 2011 essay in Women’s Art Journal, McNeely had to travel to two different hospitals in two states, with “numerous meetings among (all male) doctors trying to decide what course to take. She nearly died in the process before she was given the necessary surgeries. (One doctor presumed that she would prefer to save the child than to live.) The experience increased her awareness of how much control men had over the lives of women, and it fed her feminism.”

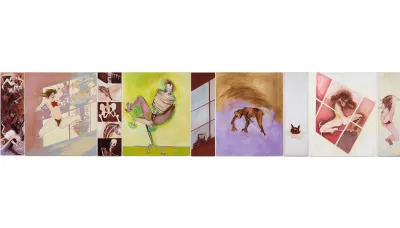

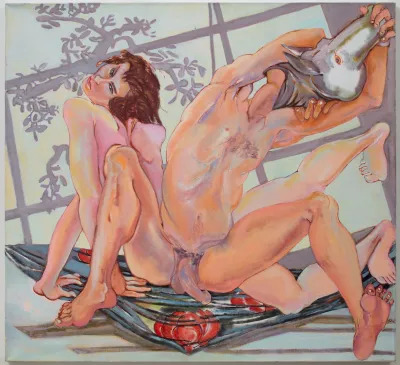

Juanita McNeely, Is It Real? Yes, It Is!, 1969. Photo Jason Mandella/Courtesy the artist and James Fuentes LLC

That harrowing experience resulted in the nine-panel 1969 painting Is It Real? Yes, It Is!, which the Whitney acquired in 2022 and quickly put on view in its permanent collection galleries. Figures are shown at awkward angles, some contorted and many in obvious pain, with limbs and joints that appear broken or mangled. At more than 12 feet by 12 feet, the overall work is monumental in scale.

For a 2022 monograph published by James Fuentes Press, artist Joan Semmel, who had been friends with McNeely since the 1970s, wrote, “Juanita opened up a world to the viewer of an imagination that had traveled through the extremes of feeling and managed to extract from it a dynamic and moving panorama of life and art, ever resistant and amazingly resilient, beautiful, rich, and alive.”

The perspective in each panel of Is It Real? Yes, It Is! varies: the center canvas shows McNeely from above, her legs in stirrups as a hand, holding a medical device, pokes through a slit in a blue medical drape; behind are X-rays of her pelvis. The bottom right panel flips the perspective: the viewer is now McNeely, staring out at the three masked doctors who are to operate on her. One panel shows a figure that is half-human, half-skeleton: this is McNeely at death’s door. As with much of her work, these scenes were often painted from memory, and there is a cinematic quality to this narrative painting.

“I was a cartoon. I was not a real person anymore. I had become a something, but not the real person,” McNeely said of how she decided to translate the experience into paint. “It’s almost making the reality a cartoon to be so horrible. That’s what I was trying for anyhow.”

In many ways, given the era, it would seem unfathomable that any of what McNeely depicted actually happened. And that was exactly McNeely’s point in choosing the work’s biting title. It’s a reality that women faced prior to 1973 that McNeely wished she had never had to paint in the first place: “I wish I had never had to make the imagery so profoundly real to me.” Her words have taken on a new valence 50 years on.

“I think the title’s also about her very ambitious decision to take on the topic of abortion in a painting,” Whitney curator Jane Panetta, who helped the museum acquire the work, says in the same video. “It’s still a taboo topic in many ways but certainly in 1969 to make this graphic a depiction of abortion was really unheard of.”

Juanita McNeely was born in 1936 in St. Louis, Missouri. Growing up she always envisioned herself attending art school and she won an art scholarship when she was 15 for an oil painting. She transformed her family’s basement into her studio and ultimately began the BFA program at St. Louis School of Fine Arts at Washington University.

Among her teachers was German artist Werner Drewes, who had studied at the Bauhaus. Also influential to her development as a painter were the works she saw by Gauguin, Matisse, and Max Beckmann at the St. Louis Art Museum. (A 1971 review by critic Hilton Kramer in the New York Times said McNeely was “still too overwhelmed by the example of Max Beckmann to be entirely persuasive in her own right, yet her energy and the reach of her imagination hold out a certain promise of things to come.”)

But this time period was also marked by several illnesses. She was hospitalized for excessive bleeding as a teenager, causing her to miss a year of high school. Then during her first year at Washington University, she was diagnosed with cancer and given three to six months to live. When the doctors told her to fill her final months with what she loved, McNeely committed herself to making art, according to Finnegan.

As McNeely said in a 2006 interview with Kate Leonard, “That was the beginning of what really formed me as someone who spoke about the things that are not necessarily pleasant, on canvas, things that perhaps most people even feel uncomfortable about looking at, much less talking about.”

But McNeely would go on to live well past that prognosis. She spent time in Mexico, and then moved to Illinois for an MFA program, despite a male professor telling her she wouldn’t make it as an artist “because you’re too skinny and you don’t look like a good fuck.” While there, McNeely also participated in a happening in 1964 with Allan Kaprow, who encouraged her to move to New York. After a year and a half in Chicago, where she taught at the Art Institute of Chicago, she ended up moving to a walk-up in the East Village.

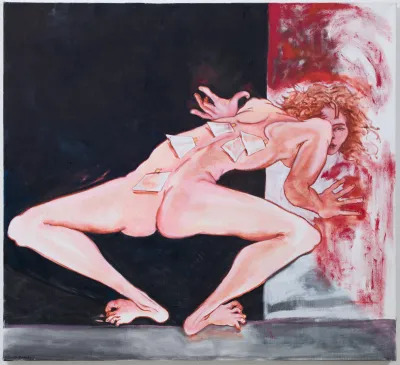

An early work that McNeely painted shortly after her arrival in New York was 1968’s Woman’s Psyche, a four-panel work in which different women are seen in various forms of what can only be described as distress and pain—they are often bleeding. Animals surround them in each scene, often as if they have just attacked these women. The work was recently acquired by the Rubell Museum and displayed in the opening hang of the institution’s DC branch.

“Juanita was an artist who used painting to delve into the deepest aspects of her life and she showed tremendous courage in the face of overwhelming adversity,” collector Mera Rubell said in a statement.

As with much of McNeely’s most powerful work, this painting deals with the lived experiences of women, told from a woman’s perspective: the difficulty of labor and birth, monthly menstruation and all that comes with it, and even raw sexuality.

At the start of the new decade, McNeely was among the first artists to move into the Westbeth Artists Housing project, and she also began showing at the artists’ co-op Prince Street Gallery in SoHo, which mounted six solo shows of her work between 1970 and 1978. McNeely also aimed to get gallery representation at this time, but like most women of her generation, she found that the commercial art world was not open to her, simply for being a woman. A director at the famed gallery Knoedler & Co. found the work strong but, upon learning that McNeely was the artist, declined to show it.

A 1971 exhibition there included Is It Real? Yes, It Is! Writing in ARTnews, critic Carter Ratcliffe described McNeely’s works as “garish, intense and frightening paintings in an Expressionist mode,” in which “themes of birth and death, sex and pain, are followed across nine canvases, melting and distorting shapes, conjuring up mythical and ritual objects from bedroom and delivery room procedure. At its climax this drama of metamorphosis seems to tattoo bodies with fragments of other bodies, as if terror were felt in a very specific personage.”

Around this time, McNeely became embedded in the feminist art movement, befriending artists like Joan Semmel and Marjorie Kramer and feminist art historian Pat Mainardi. McNeely attend meetings for feminist groups like Redstockings and W.A.R. (Women Artists in Revolution). She joined the Fight Censorship Group, which was founded by artist Anita Steckel as a response to several women artists’ work being dismissed because it was considered too erotic or overly sexual; other artists who joined include Semmel, Hannah Wilke, Louise Bourgeois, Judith Bernstein, Martha Edelheit, Eunice Golden, and more.

Despite her success throughout the 1970s, McNeely’s art seemed to lose favor in the New York art world. Her CV lists only a handful of group shows in the 1980s and ’90s, and even fewer solo shows during that time period. In 1982, she moved to France for six months during a teaching sabbatical. That trip also resulted in a tragic accident that damaged McNeely’s spinal cord, which ultimately required her to use a wheelchair.

For a decade, between 1996 and 2006, she didn’t have a solo show, until intrepid dealer Mitchell Algus mounted a solo of McNeely; he would mount two more, in 2016 and 2018. In 2014, she was the subject of her first—and to date only—major institutional survey, titled “Indomitable Spirit,” at the Women’s Studies Research Center at Brandeis University in Massachusetts. In an accompanying catalogue, exhibition curator Susan Metrican writes, “Unabashed in her vision of woman that is both sensual and macabre, McNeely portrays her monumental figures with a visceral dexterity. … Indomitable Spirit embodies all the energy, courage and forthrightness that it took to challenge how the world views women and their roles in society.”

With her star on the rise over the past decade, McNeely began working with closely watched New York dealer James Fuentes, who has mounted three in-person exhibitions and two online showings of her work since 2020. Her first solo exhibition in Los Angeles is currently on view at Fuentes’s recently opened space there; it has been extended to November 18. That exhibition features just three multi-panel works from the mid-’70s, including two incredibly spare ones in which fragments of figures are set against stark white backgrounds, as if they are falling.

In an email to ARTnews, Fuentes said, “Working with Juanita McNeely has been one of the great highlights of my career. For Juanita to be able to experience well-deserved recognition and support during her lifetime has been a true gift. Her work will remain a testament to the power an artist has to process, channel, and articulate trauma as a way to invent and heal. We can all learn something from her example.”

Through it all, McNeely never faltered in her dedication to painting the world as she saw it—the world as many women see it—full of a range of experiences, including ones that polite society would rather they not talk about. As she once said, “Many times, life’s forces are more powerful than we are, and yet we can face them if we have a standing ground that is our own, that we’ve set for ourselves.”