Editor’s Note: This story is part of Newsmakers, a new ARTnews series where we interview the movers and shakers who are making change in the art world.

Artist Kathryn Andrews has long been interested in disrupting established systems by inviting viewers of her wide-ranging practice to join in actively interrogating common subjects of the American zeitgeist. The Judith Center, her latest project, however, extends beyond a traditional studio practice and even art-making itself. The nonprofit assembles experts in their respective fields to research topics that prod gender equality across the United States. Artists are then invited to create posters based on the research that are exhibited together in museums. The Judith Center is also establishing a physical location in Los Angeles in January 2025 that will host conversations and events open to the community.

ARTnews spoke with Andrews about her approach to the Judith Center, goals for research, and the rich history of posters.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and concision.

ARTnews: Tell me about the Judith Center and how it all started.

Kathryn Andrews: In 2020, I made an artwork that was displayed on the facade of DePaul Art Museum [in Chicago], made in response to the imminent presidential election, depicting the heads of many of the presidents from the 20th century. Atop it was the names of all the women that had run for the presidency [and lost]. When you see all the quantity, it’s really shocking. Women have been fighting for so long for representation.

In conjunction with that show, I organized a panel bringing together women from many disciplines: a legal historian from DePaul, a researcher from the Center for American Women in Politics, and the lead cinematographer from the Kamala Harris Vice Presidential campaign. We had a conversation about the current state of sexism in the United States and the challenge women have had in trying to gain equal representation, not only in the sphere of politics, but across various fields.

What I saw in that exchange was that there’s so much to be learned. When we’re in our own professional sphere, we don’t understand the intricacies of how bias in one field produces bias in other fields. I was so inspired that this arena had not been largely explored, and I thought, How can we look at this problem through a cross-disciplinary lens? What new information would that reveal?

Shortly after that, I began working on creating the Judith Center. I decided that it would serve multiple purposes, engaging a range of initiatives, but at its core, it would center around the arts and be educational in nature.

What projects are being worked on at the Judith Center?

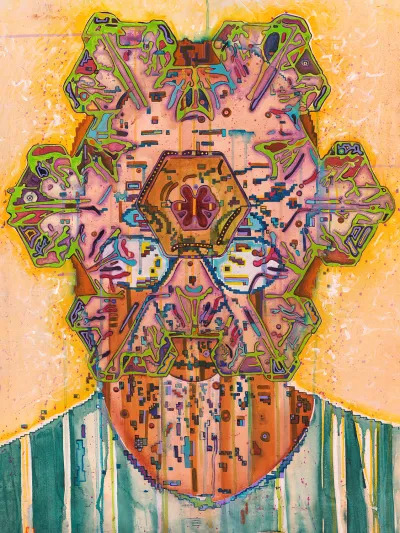

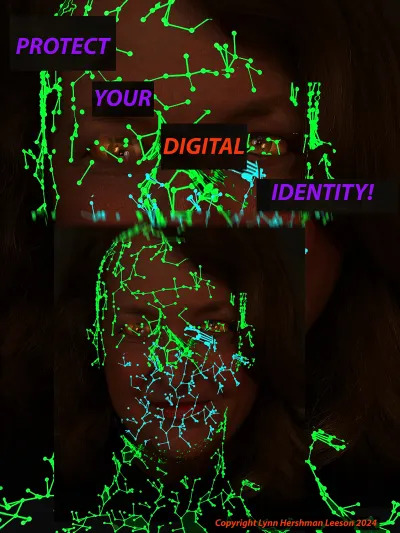

Our very first initiative is called the Judith Center Poster Project. It will consist of 50 posters produced by 50 contemporary artists, including women, non-binary persons, and men who either are American or have a very strong connection to the U.S. We’re partnering with many university art museums to exhibit these posters over a five-year period. The posters touch upon topics of great importance in the regions of our collaborating partners. I’m thinking of the project as a survey of contemporary sexism in the US.

For example, our first drop, which is now on view at the Broad Art Museum at Michigan State University, addresses new technologies, gender, and freedom of expression. We convened a panel on how AI is impacting the electoral process and, as a result, certain groups are disadvantaged.

One of the reasons why we’re doing it there is because Michigan State University has a large focus on science research, and many people within the university are not only using AI, but also deeply engaged in producing new technology. Personally, I wanted the project to debut there because of the history of violent threats against female politicians in the state.

And every time it travels there is a new iteration of the project?

Yes, five artists will produce five posters that come out twice each year. The next time it occurs, there will be a new topic.

What drew you to doing poster projects?

There is a very rich history of political printmaking that has not been adequately publicly historicized partially because that work was done by women. Posters have long been used to talk about critical social issues, while targeting mass audiences because they are cheap to produce and distribute. This medium has been important in the fight for gender equality. We want to foreground some of that history as we consider the questions of sexism that are ongoing today.

Will there be a public engagement component extending beyond the art world and universities?

The posters will be exhibited primarily at university art museums and at a few independent art museums. Our audience is museumgoers. I decided that these kinds of venues offer so much opportunity—not only can we engage with students coming through the system and beginning to think about how our everyday lives are fashioned, but we can also engage with the public in the museum’s locale. We can also engage with academic communities consisting of some of the most forward-thinkers on these questions. So, it offered a really rich setup.

We’re also launching a new space in downtown Los Angeles in January, with programming that will be open to the public. We will also offer programming in other settings. This past spring, for instance, we did a program at the Felix Art Fair. It’s possible that we could extend to a wider audience, but because most of our programming centers around art, we’re going to go to the spaces where that’s welcome.

What can we expect to see in the new LA space?

There are several other initiatives that we are developing. One is called Poetry X___, which will feature writing workshops and poetry readings. Beyond producing art that engages people, we want to offer a space that can be a resource for communities that are underserved. There, we imagine helping writers to find their voice.

Others include a book club and a data visualization project, where we’re working with different designers to create a central repository of facts about gender oppression. We will also host an oral history project where we hope to have different artists and persons in the arts engage in conversations around histories of underrecognized work produced by women artists.

What kinds of discussions do you hope to bring to the forefront with the Judith Center?

Much of what we’re talking about are questions that are examined in, say, gender studies departments and universities. People historically have thought about gender studies as being a woman’s problem. We’re thinking about it differently. We’re very interested in inviting men and non-binary persons to the conversation. By looking at questions of masculinity and by considering the contributions of queer theory and other lines of thought, we want to explore, publicly, what’s fed to us by the culture at large.

One topic we’ve been developing content around is domestic violence, and how that varies in rural communities as opposed to urban ones. With the overturning of Roe v. Wade, there’s a direct impact on rural locales because there is a higher incidence of unwanted pregnancies there. This matters because domestic violence increases when there is a greater occurrence of unwanted pregnancy.

One of our partners is based in a rural location in a former Underground Railroad safe house, surrounded by mounds constructed by Native Americans. In this location, there is a layering of histories of violence coupled with limited resources. We want to better understand how these issues correlate and the ways in which they are exacerbated. We also want to understand more about what’s going on with the mindset of nurses and first responders in these settings. What messaging are they receiving? What are the legalities there? And what’s happening with the police? All these factors add up to create a particularly toxic mix for both victims of abuse and their abusers.

What do you hope to gain from conducting these kinds of efforts?

We’re interested in spotlighting the complex histories that have brought us to where we are, and then asking questions from new directions. We want to bring together people from various fields who can begin to unpack some of these structures’ constraints across disciplines.

The information learned during the research process informs the creation and curation of the posters in response. We produce these conversations for the public, and over time, as more posters are produced, they will be exhibited en masse, with the idea that audiences will then have the opportunity to understand the full picture.

Have there been any surprises since beginning the Judith Center?

One of the biggest surprises has been how men don’t conceptualize gender inequality as their problem and the degree to which women have internalized sexism as normal. I conducted several focus groups early on. When I was telling women in these groups what I was doing, I was encountered with sentiments like, “Oh, yeah, good luck, that’s not going anywhere.” And when I said, “Well, we’re going to do it anyway.” The women then got very excited, as if it was a new idea that we could actually create change. There are many other examples, but the degree to which this phenomenon is so ingrained in our culture has surprised me. In meeting people working in this space for a long time, I’ve come to appreciate how courageous they are, persevering despite the odds. I’m still optimistic that change is possible.

Newsmakers: Jonathan Lethem Discusses His Abstract and Novelistic Book About Art

Newsmakers: Visual AIDS Executive Director Kyle Croft Reflects on 35 Years of ‘Day Without Art’

One of the World’s Best Restaurants Is Hitting the Road With a 12-Course Omakase Dinner

Inside Graphic Image and GiGi New York’s Unique Manufacturing Facility

Incogni helps stop scam calls and removes your info from data brokers

Doc Rivers Wants Vegas Expansion—but NBA Cup Hasn’t Moved Needle