One could be forgiven for thinking they’ve had enough Picasso. Last year, during the 50th anniversary of Pablo Picasso’s death, museums across the globe overindulged in works by the Spaniard to the point of nausea. Critics slammed the torrent of exhibitions and gallery shows, often looking for the worst in the life and work of an artist who has been picked over for decades.

The Guardian said Picasso’s “appeal is as a picaresque who left a trail of destruction in his wake: abandonments, betrayals, suicides.” ARTnews, in a comprehensive roundup of the Picasso-mania, said the “glut of exhibitions in 2023 taught us absolutely nothing.”

But not all shows are the same, and there are as many ways of organizing a show as there are paintings.

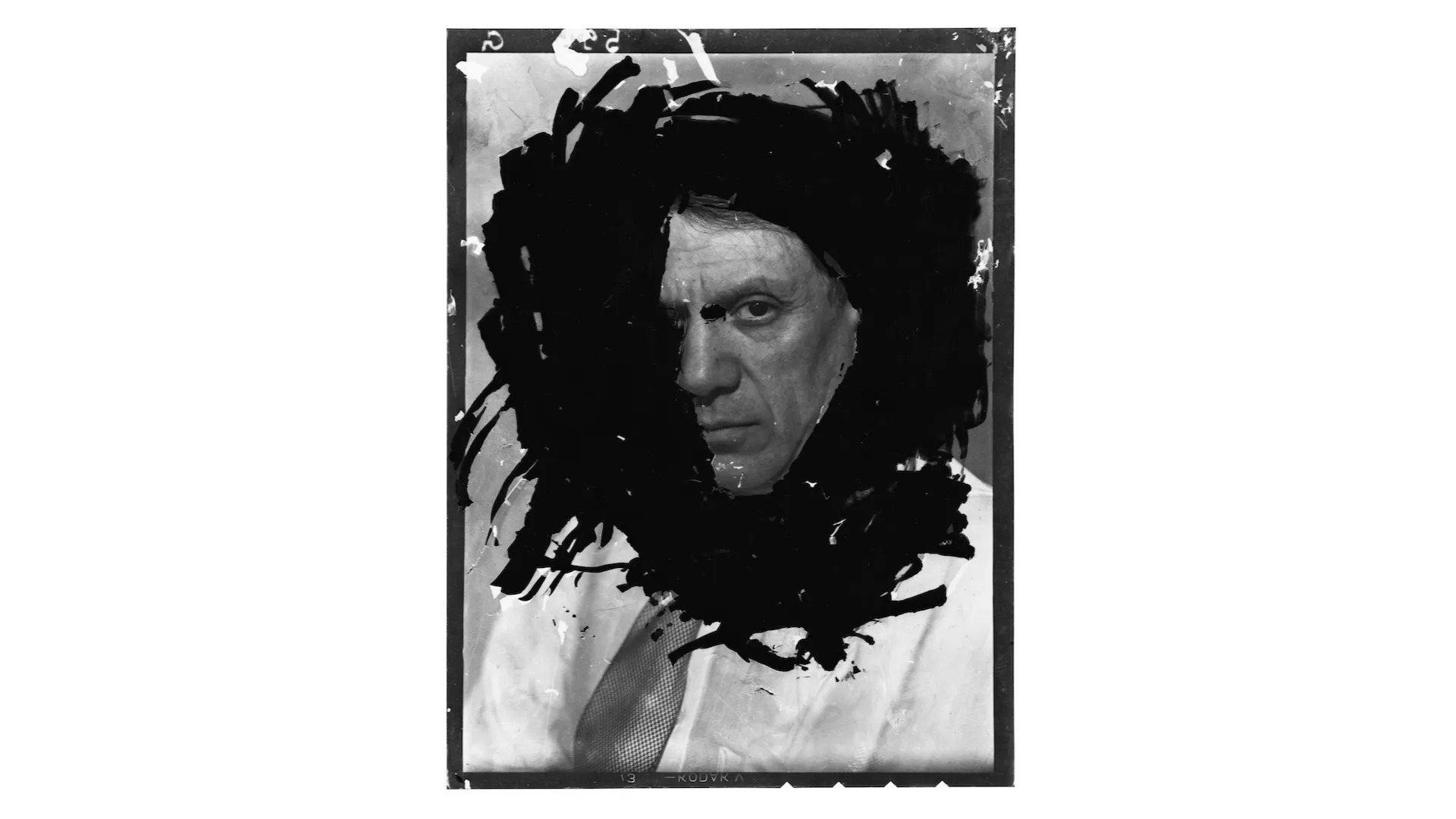

At Gagosian, through February 10, is the most unique Picasso show among the droves, “A Foreigner Called Picasso.“ Organized by the writer and historian Annie Cohen-Solal and the art historian Vérane Tasseau, the show looks at Picasso’s life as an immigrant in France, a country riddled with xenophobia—hardly the normal angle for a show about the artist. (Or a book, for that matter: Cohen-Solal also published a related Picasso biography with a similar title that has garnered acclaim in both France and the US.)

Shortly after arriving in Paris, in 1900, from his hometown in Málaga, Spain, Picasso became a target. Like the torrent of Spanish immigrants before him, the 19-year-old painter settled down in Montmartre, where he was surrounded by people who spoke his language. Within a year, thanks to his relationship with the art dealer and anarchist Pierre Mañach, Picasso was surveilled by the police who, like the Académie des Beaux Arts, couldn’t trust a foreigner who mingled with political radicals, lived in a slum in a filthy neighborhood, and, worst of all, embraced the avant-garde.

Following the the opening of France’s National Museum of Immigration in 2015, Cohen-Solal was given access to the file on Picasso that police began compiling shortly after he arrived in France.

“I became very intimate with the files and learned that alongside this genius of an artist, there was a genius political strategist who gave himself agency in a culture and country that rejected him at every turn,” Cohen-Solal told ARTnews.

At the time, France was experiencing waves of xenophobia. In 1894, French president Sadi Carnot was assassinated by an Italian national and avowed anarchist; that same year was the one that kicked off the Dreyfus Affair, in which a Jewish French Army captain was wrongly convicted of sending military secrets to the Germans.

Cohen-Solal said she wanted to view Picasso from the perspective of that anti-foreigner sentiment. Essentially, she put his life before his art.

“I love art historians,” Cohen-Solal said, “but they are always tempted to keep Picasso for themselves and look at him through a prism of formalism. I want to open Picasso as a subject to the social scientists, anthropologists, economists. If you let him breathe, he is a jewel to work from.”

“The show isn’t so much about Picasso’s work, but about his life and how he was able to navigate a system that was working against him,” said Gagosian director Michael Cary.

Wall text gives context to the show’s galleries, which each cover a portion of the years between 1900 and 1973 that Picasso spent in France. But unlike a traditional museum show, the works hang far from their titles, which means visitors must piece together the narrative, without contextual information. (Many of the works came from private collections and museum loans, thanks to Larry Gagosian’s far-reaching influence.)

Some of the standouts are set in a section covering the years 1919–1939, shows how much the artist developed as a “persona non grata” who was labeled “a ‘foreigner’ in France, a ‘degenerate’ artist in Nazi Germany, an ‘enemy’ under Franco’s Spain” and includes many of Picasso’s most famous subjects in Classic, Cubist, Surrealist styles. The mélange of styles in this gallery says quite a bit about where Picasso was an artist at the time.

After the outbreak of World War I Picasso’s first dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, was forced out of France thanks to his German citizenship. Kahnweiler’s decision to live in exile in Switzerland effectively canceled whatever contract he had with Picasso, who then began working with the dealer Paul Rosenberg. “But his relationship with Rosenberg is interesting because Rosenberg didn’t like Cubism,” Cary said during a walk through of the show. “And so there’s a little bit of a strategy involved where Picasso may have been trying out different styles responding to all Rosenberg’s needs for his clientele.” While that section of the show highlights Picasso’s mastery of neoclassical painting still lives on top of the Cubism he pioneered, it also reveals an often overlooked detail about the painter. There was a time when he, like everyone else, worked for money and likely understood that the customer is always right.

“Picasso wasn’t a ‘genius,’ he wasn’t a ‘monster’—he was an artist,” Cary told ARTnews later via email, noting that a really prolific artist may make 5,000 works in a lifetime whereas Picasso made 25,000. “You could have visited every exhibition across Europe and the US for the anniversary year (2023) and only scratched the surface of his oeuvre.”

But have there really been too many Picasso shows? Yes and no, Cary said.

“Picasso fatigue is a real thing (especially among Picasso scholars!),” he added. “You may grow tired of thinking about Picasso…but the only way through it is to look again. Thinking and reading and writing about Picasso is not equivalent to that empirical experience. Not even close. To look, we need pictures hanging on walls—everywhere and always and over and over again. I may not always want to talk about Picasso, but I’ll always want to see it.”

Cecile Debray, president of the Picasso Museum in Paris, would likely agree with Cary. She sees the Gagosian show as one of the many new approaches to Picasso’s work. “Turning Point,” an exhibition at the Museo Reina Sofía organized by Eugenio Carmona, also stands out, she told ARTnews, for considering Picasso’s “radical approach to the body” and how many of his figures were what today would be called “gender fluid.”

When asked about the famously botched “Pablo-matic” show at the Brooklyn Museum, for which the Picasso Museum loaned a few works, Debray said she thought “they would work more precisely on the question of femininity.”

Debray called for a complex reading of Picasso’s representations of women. In the 1970s and ’80s, the art historian Rosalind Krauss praised Picasso, she pointed out, and spoke about separating the woman and the art and justified political readings of Picasso’s work. “Now, it’s totally the opposite,” according to Debray. “You only have biographical readings. Young people and neo-feminists only see women suffering.”

However, the Brooklyn Museum show was important to the debate, she said, as are shows based on historical aspects, like a presentation of El Greco and Picasso at the Prado and a survey of his drawings at the Centre Pompidou.

“When you think you know everything about Picasso, you’re wrong,” she said. “There is always something new to discover.”

Richard Prince and Galleries Settle in Closely-Watched Copyright Lawsuits

Activists in Madrid Call for Ceasefire in Gaza at Madrid’s Reina Sofía Museum

Everything We Know About ‘The White Lotus’ Season 3

How Sofia Vergara’s Makeup Transformed Her ‘Exotic Face’ Into Drug Lord Griselda Blanco With Bucked Teeth, Prosthetics and Flat Hair in Netflix Drama

How to unlink Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger accounts: Move to Europe

Vince McMahon Sex Trafficking Lawsuit Could Turn on NDA