Wikimedia Commons

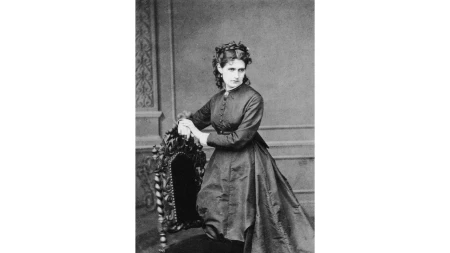

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot was the first female member of the Impressionist movement and perhaps its most constant participant. She was born into a bourgeois family in Bourges, France, in 1841. Her father, Edmé Tiburce Morisot, was the prefect of the Cher department, in central France. Her mother, Marie-Joséphine-Cornélie Thomas, may have been the great-niece of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, but this connection has come under question.

Berthe had a brother and two sisters, including one, Edma, with whom she learned to paint. At that time, women were not allowed into the École des Beaux-Arts de Paris, so the sisters were instructed privately, first by Geoffroy Alphonse Chocarne, then Joseph Guichard, Achille Oudinot, and Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot. They both made their debut at the 1849 Salon in Paris. While Edma eventually quit painting, Berthe kept going.

Morisot, whose family moved to Paris when she was young, would spend afternoons copying the great masters at the Louvre, where she met Henri Fantin-Latour and Édouard Manet. At age 33 she married Manet’s younger brother, Eugène, who was extremely supportive of her career.

Among her many other works, Morisot painted about 70 portraits of their daughter, Julie, and when Berthe died, in 1895, Julie made it her life’s mission to keep her mother’s memory alive, by collecting her works and exhibiting them regularly with the help of her husband, the painter Ernest Rouart. Thanks to Michel Monet’s bequest in 1966 and a donation from Julie Manet’s children in 1990, the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris now holds the world’s leading collection of works by Morisot in the world.

Here are seven essential paintings from her nearly 50-year career.

An exhibition of Morisot’s paintings is on view at the Dulwich Picture Gallery through September 10, 2023.

-

The Sisters (1869), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Image Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. These two women with pale skin and dark hair are shown, as often in Morisot’s works, from the lap up. Both have straight, dark brows; delicate noses; smooth skin; and closed, rose-pink mouths. Both wear black ribbons around their throats and high-necked white dresses with ruffles under the chins and at the wrists. The one on the right holds an open fan in her lap. The other wears a gold ring with a dark, oval stone. Like many female figures Morisot painted at the time, they look serious, almost withdrawn into silence.

The close resemblance between the two women, the rigorous reproduction of their outfits and hair, and the similarity in their postures create an intriguing mirror effect, even an impression of twinship. Since the work was done in 1869, the year Edma Morisot got married, the logical interpretation would be to identify the sitters as Morisot siblings, but this is actually a double portrait of sisters named Delaroche. Berthe was not quite satisfied with the work and decided not to show it at the 1870 salon.-0

-

The Cradle (1872), Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Image Credit: Copyright © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt. This is one of Morisot’s most famous paintings. In it, the artist represented her sister Edma watching her daughter Blanche sleep—the first evocation of motherhood in Morisot’s work. The theme would return later, as she became a mother herself in 1878. The eyes of the figures align with each other along a diagonal, as well as their left arms, suggesting an unbreakable bond, while the veil partially enclosing them conveys a feeling of intimacy.

Morisot presented The Cradle at the first Impressionist Exhibition, in 1874, as the first female member of the movement, against the advice of Manet, who preferred featuring at the official Salon (She would go on to participate in all the group’s shows except in 1879, the year after she gave birth to Julie.) Though The Cradle received favorable comments from critics, Morisot failed to sell this particular painting. It remained in her family until its acquisition by the Louvre in 1930.

-

Woman at Her Toilette (1875–80), Art Institute of Chicago

Image Credit: Art Institute of Chicago. This is one of the highlights of the Art Institute of Chicago, which holds the second-largest collection of Impressionist art in the world after the Musée d’Orsay. It was showcased at the second Impressionist Exhibition, which took place at Paul Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1876. In the 1870s, Morisot focused on portraits of young women getting ready to go out. Unlike Mary Cassatt or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, she would put them in intimate indoor settings rather than in the context of a ball or the theater. Here, it is unclear whether the model is tying up or untying her hair. The nervousness in the brushstrokes is at odds with the gracefulness of the young woman.

The composition reminds one of Before the Mirror by Manet, also featuring a young woman fixing her hair, seen from behind. It was painted in 1876, one year after Woman at Her Toilette, which suggests that Manet, who is often viewed as Morisot’s mentor, also drew inspiration from her. Woman at Her Toilette did not go unnoticed. In fact, it was the toilette series that really put Morisot on the map. Another work in the series, Young Girl in a Ball Dress (1879), would later become the first Morisot work to enter a museum collection. It was bought for the French state in 1894 and hangs in the Musée d’Orsay.

-

Summer (Young Woman by a Window) (1879), Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Image Credit: Copyright © Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole/Frédéric Jaulmes. This elegant young lady—is she sitting inside or outside? This is exactly the effect Morisot was looking for. The whole is painted so loosely that the indoor and outdoor worlds seem to collide. Brilliant light refracts from the young woman’s ruffled blouse and from the flowers behind her. In this composition the model and nature could be perceived as one.

Summer (Young Woman by a Window) is evocative of Morisot’s interest in intermediate spaces, from doorsteps to balconies to verandas, which to her are all extensions of bourgeois interiors. The depiction of such spaces caused a new genre to emerge, one where plein air meets intimacy. The representation of a young woman on the threshold of adulthood can be seen as a metaphor for the artist on the threshold of recognition.

-

Paule Gobillard (1887), Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Image Credit: Copyright © Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris. Morisot taught her daughter and her nieces how to paint. Her most diligent and talented student was Paule Gobillard (1867–1946), the elder daughter of her sister Yves Gobillard. After copying the Masters during trips with her aunt to the Louvre, 20-year-old Paule obtained her own copyist card. It may be to celebrate this accomplishment that Morisot decided to represent her at an easel.

She appears from the side, with a palette in one hand and a brush in the other. It is the only portrait of this young artist in which she wears something other than a ball gown. Unlike her younger sister Jeannie and cousin Julie, Paule Gobillard made an art career for herself; in that sense she is considered to be Morisot’s official successor. This painting was held by the Morisot-Rouart family until 1961 and now hangs in the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris.

-

Self-Portrait (1885), Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Image Credit: Copyright © Musée Marmottan Monet. Among the five self-portraits known to exist, four show Morisot with her daughter. The Musée Marmottan Monet is home to the only one where the artist, age 44, stands alone, palette and brushes in hand.

The background was loosely painted; over the years Morisot had gained rapidity and become a master of the non finito. Her figure stands out against a neutral background. We see her in side view, though her head is turned toward the viewer. Is she staring at us? Produced at a time when women did not have the right to apply to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, this painting could appear as a manifesto: Morisot representing herself on the same level as her male counterparts and close friends Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet—as an accomplished artist.

The Sisters (1869), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

These two women with pale skin and dark hair are shown, as often in Morisot’s works, from the lap up. Both have straight, dark brows; delicate noses; smooth skin; and closed, rose-pink mouths. Both wear black ribbons around their throats and high-necked white dresses with ruffles under the chins and at the wrists. The one on the right holds an open fan in her lap. The other wears a gold ring with a dark, oval stone. Like many female figures Morisot painted at the time, they look serious, almost withdrawn into silence.

The close resemblance between the two women, the rigorous reproduction of their outfits and hair, and the similarity in their postures create an intriguing mirror effect, even an impression of twinship. Since the work was done in 1869, the year Edma Morisot got married, the logical interpretation would be to identify the sitters as Morisot siblings, but this is actually a double portrait of sisters named Delaroche. Berthe was not quite satisfied with the work and decided not to show it at the 1870 salon.-0

The Cradle (1872), Musée d’Orsay, Paris

This is one of Morisot’s most famous paintings. In it, the artist represented her sister Edma watching her daughter Blanche sleep—the first evocation of motherhood in Morisot’s work. The theme would return later, as she became a mother herself in 1878. The eyes of the figures align with each other along a diagonal, as well as their left arms, suggesting an unbreakable bond, while the veil partially enclosing them conveys a feeling of intimacy.

Morisot presented The Cradle at the first Impressionist Exhibition, in 1874, as the first female member of the movement, against the advice of Manet, who preferred featuring at the official Salon (She would go on to participate in all the group’s shows except in 1879, the year after she gave birth to Julie.) Though The Cradle received favorable comments from critics, Morisot failed to sell this particular painting. It remained in her family until its acquisition by the Louvre in 1930.

Woman at Her Toilette (1875–80), Art Institute of Chicago

This is one of the highlights of the Art Institute of Chicago, which holds the second-largest collection of Impressionist art in the world after the Musée d’Orsay. It was showcased at the second Impressionist Exhibition, which took place at Paul Durand-Ruel’s gallery in 1876. In the 1870s, Morisot focused on portraits of young women getting ready to go out. Unlike Mary Cassatt or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, she would put them in intimate indoor settings rather than in the context of a ball or the theater. Here, it is unclear whether the model is tying up or untying her hair. The nervousness in the brushstrokes is at odds with the gracefulness of the young woman.

The composition reminds one of Before the Mirror by Manet, also featuring a young woman fixing her hair, seen from behind. It was painted in 1876, one year after Woman at Her Toilette, which suggests that Manet, who is often viewed as Morisot’s mentor, also drew inspiration from her. Woman at Her Toilette did not go unnoticed. In fact, it was the toilette series that really put Morisot on the map. Another work in the series, Young Girl in a Ball Dress (1879), would later become the first Morisot work to enter a museum collection. It was bought for the French state in 1894 and hangs in the Musée d’Orsay.

Summer (Young Woman by a Window) (1879), Musée Fabre, Montpellier

This elegant young lady—is she sitting inside or outside? This is exactly the effect Morisot was looking for. The whole is painted so loosely that the indoor and outdoor worlds seem to collide. Brilliant light refracts from the young woman’s ruffled blouse and from the flowers behind her. In this composition the model and nature could be perceived as one.

Summer (Young Woman by a Window) is evocative of Morisot’s interest in intermediate spaces, from doorsteps to balconies to verandas, which to her are all extensions of bourgeois interiors. The depiction of such spaces caused a new genre to emerge, one where plein air meets intimacy. The representation of a young woman on the threshold of adulthood can be seen as a metaphor for the artist on the threshold of recognition.

Paule Gobillard (1887), Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Morisot taught her daughter and her nieces how to paint. Her most diligent and talented student was Paule Gobillard (1867–1946), the elder daughter of her sister Yves Gobillard. After copying the Masters during trips with her aunt to the Louvre, 20-year-old Paule obtained her own copyist card. It may be to celebrate this accomplishment that Morisot decided to represent her at an easel.

She appears from the side, with a palette in one hand and a brush in the other. It is the only portrait of this young artist in which she wears something other than a ball gown. Unlike her younger sister Jeannie and cousin Julie, Paule Gobillard made an art career for herself; in that sense she is considered to be Morisot’s official successor. This painting was held by the Morisot-Rouart family until 1961 and now hangs in the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris.

Self-Portrait (1885), Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Among the five self-portraits known to exist, four show Morisot with her daughter. The Musée Marmottan Monet is home to the only one where the artist, age 44, stands alone, palette and brushes in hand.

The background was loosely painted; over the years Morisot had gained rapidity and become a master of the non finito. Her figure stands out against a neutral background. We see her in side view, though her head is turned toward the viewer. Is she staring at us? Produced at a time when women did not have the right to apply to the Académie des Beaux-Arts, this painting could appear as a manifesto: Morisot representing herself on the same level as her male counterparts and close friends Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet—as an accomplished artist.

RobbReport

This $30 Million L.A. Mansion Comes With Breathtaking Ocean Views and a Giant Infinity Pool

WWD

Chiara Ferragni Secures New Investor

BGR

Apple stops signing iOS 16.5 after iOS 16.5.1 rollout

Sportico

Sporticast: Breaking Down F1’s Billion-Dollar Business Rise

SPY