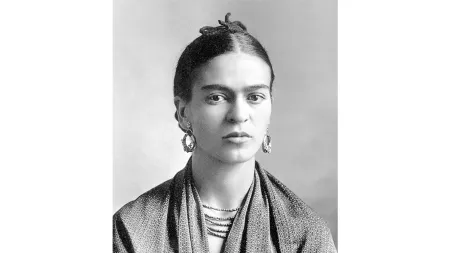

Pictures From History/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

In a drabber parallel universe, Frida Kahlo might have been a doctor. As a high schooler she was on a pre-med track, studying biology, anatomy, and zoology at one of Mexico City’s best schools, one of only 35 girls in a student body of around 2,000. But then a trolley car collided with the bus she was taking home, forever derailing her health and catapulting her onto a new course. We’ll never know what kind of physician Kahlo would have made, because she became a painter of striking autobiographical canvases instead.

In her short but fiercely lived life, the Mexican artist produced between 150 and 200 paintings, most of them self-portraits, depictions of family and friends, and still lifes. Figurative and intensely personal, her paintings fuse folklore and symbolism to illustrate her lived experience. They often combine binary elements—night and day, masculine and feminine, being in two places at once, or dual versions of Kahlo herself.

The version of herself that she shared with the public, a distinct persona of bohemian Mexicanidad and liberal politics, is part of what still renders her a pop culture icon today (a new documentary will premiere at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival). Kahlo entranced many significant 20th-century photographers—including Lola Álvarez Bravo, Carl Van Vechten, Nickolas Muray, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, Julien Levy, and Dora Maar—who left behind exposures of the artist that continue to fuel our fascination with all things Frida Kahlo.

-

Early beginnings

Image Credit: Schalkwijk/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño/Mexico City. Born on July 6, 1907, Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón grew up in the Mexico City suburb of Coyoacán in a blue house built by her father and nicknamed the Casa Azul. (She’d later amend her birth year from 1907 to 1910 so that it coincided with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution that she held so dear.) Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was a German-Jewish photographer, and her mother, Matilde Calderón, was a Catholic of indigenous and Spanish heritage. Kahlo was the third of four sisters and close with her father, who trained her to help him in the photography studio from a young age.

When she was six years old, Kahlo contracted polio, which rendered her right leg and foot permanently smaller than her left. More than just a fashion statement emphasizing her Mexican identity, the floor-length skirts that would become part of Kahlo’s uniform were a way to deflect attention from this deformity.

In 1922 Kahlo started studying at Mexico City’s Escuela Nacional Preparatoria with a focus on sciences and became part of a group of communist activist students called Las Cachuchas (“The Caps”). During her years there, los tres grandes (the big three artists of Mexican Muralism—David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco) all worked on early murals at her school. Kahlo met Rivera briefly when he was painting in the school amphitheater; they wouldn’t meet again until 1928.

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo and her boyfriend were riding a bus that collided with a trolley car. Some passengers were killed; Kahlo sustained fractures of her spine, right leg, collarbone, pelvis, and right foot and serious internal injuries. Hospitalized for a month after the accident, Kahlo was fitted with a plaster corset, versions of which she would have to wear for the rest of her life. Due to her injuries from this accident, she later had multiple miscarriages and therapeutic abortions and underwent more than 30 surgical procedures.

Kahlo started painting during her long recovery in bed. Using a portable easel and a mirror that her mother had installed on the underside of her four-poster bed, Kahlo began with the most readily available subject: herself. It was a subject she would return to again and again as she used self-portraits to illustrate her inner world during distinct moments in her eventful life.

-

Kahlo and Rivera

Image Credit: Ben Blackwell. Artwork copyright © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. A few years after her recovery Kahlo again met Rivera through a friend, photographer Tina Modotti. Twenty years older than Kahlo, Rivera was by then an established artist. They married on August 21, 1929, forming a union that proved both turbulent and enduring. They divorced and quickly remarried. They each had affairs, sometimes with the same people. Kahlo’s liaisons famously included one with Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky (who temporarily lived in the Casa Azul during his exile in Mexico) and another with Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Kahlo and Rivera spent the early years of their marriage in the United States, with a recent book (Frida in America, 2020) positing that Kahlo experienced her “creative awakening” there and made important work while living in San Francisco, New York City, and Detroit. Kahlo arrived in San Francisco in 1930 as a 23-year-old, having never crossed the border before. “Dressed in native costume even to huaraches, she causes much excitement on the streets of San Francisco,” noted Edward Weston, who photographed the couple around that time. “People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.” He called her “a little doll alongside Diego, but a doll in size only, for she is strong and quite beautiful.”

This description could extend to Kahlo’s portrayal of herself in the marriage portrait she produced while living in San Francisco, Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931). Exaggeratedly smaller than Rivera, Kahlo and her tiny feet seem almost to float above the floor, and yet she has a look of strength that is underscored by the fiery red of her shawl.

-

Kahlo in America

Image Credit: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Maria Rodriguez de Reyero Collection, New York. Weston was one of many artists Kahlo befriended while in the United States. Not long after arriving in San Francisco she met photographer Dorothea Lange, who shared her studio and introduced Kahlo to someone who became a lifelong confidant, Dr. Leo Eloesser. Eloesser was one of Lange’s clients, and after meeting Kahlo he carefully diagnosed her injuries and remained one of her most trusted friends until her death.

While in America, Rivera was the one sought out for mural commissions and other projects. Kahlo was still emerging as an artist but certainly left an impression. “I think,” said Imogen Cunningham, who photographed Kahlo in San Francisco, “that she was a better painter than Diego. She never got any credit.” Indeed, a 1933 article about her published in a Detroit newspaper was headlined “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art,” placing Kahlo firmly in the shadow of her better-known partner. Still, she was not without confidence: “Of course, he does well for a little boy,” she quipped about Rivera in the article. “But it is I who am the big artist.”

Already at this early stage of her career, Kahlo was confident in a dreamlike style that nevertheless communicated her personal experience.

-

Kahlo the big artist

Image Credit: Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection Madison Museum of Contempory Art. Kahlo’s career shifted around 1938 as her work began to gain recognition. She made her first-ever sale that summer, when Hollywood actor and collector Edward G. Robinson visited Rivera’s studio. Rivera showed Robinson Kahlo’s paintings, and the actor bought four canvases for $200 each. Kahlo later wrote, “For me it was such a surprise that I marveled and said, ‘This way I am going to be able to be free. I’ll be able to travel and do what I want without asking Diego for money.’”

A few months later, Kahlo had her first solo show, one of only two mounted during her lifetime, exhibiting 25 paintings at New York’s Julien Levy Gallery. The November opening drew an A-list crowd including Alfred Stieglitz, curator Alfred H. Barr, art historian Meyer Schapiro, and Georgia O’Keeffe (whom Kahlo had befriended on her first trip to New York). André Breton, who had met Kahlo in Mexico and called her a Surrealist (a label she rejected, since she believed her work represented her lived reality), wrote a catalog essay describing Kahlo’s work as “a ribbon around a bomb.” Time magazine reviewed the show, reporting that “too shy to show her work before, black-browed little Frida has been painting since 1926, when an automobile smashup put her in a plaster cast, ‘bored as hell.’”

Kahlo exhibited Pitahayas (1938) at Julien Levy, one of the roughly 30 still-life paintings she executed during her life (as compared with around 80 self-portraits). The oil-on-aluminum work shows five rotting pitahaya fruits leaning against volcanic rocks and a cactus, one sliced open as a small sketched figure of a skeleton points a scythe in its direction. Pitahayas and 17 other paintings traveled directly from New York to Paris, where in 1939 Kahlo participated in a group show of Mexican art at the Pierre Colle Gallery. The show was arranged by Breton with help from Marcel Duchamp, whom Kahlo described as “the only one among the painters and artists here who has his feet on the ground and his brains in their place”).

Among the works in the exhibition was The Frame (1938), a portrait of herself crowned with yellow flowers that Kahlo inserted into the center of a small, reverse glass painting of blossoms that she had bought in Oaxaca. The work was acquired by the French state and now is part of the Centre Pompidou collection. (Though Kahlo’s oeuvre is relatively small, her works would eventually land in other high-profile collections as well, such as New York’s Museum of Modern Art, SFMOMA, Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Moderno and the National Museum of Women in the Arts.)

-

Back to the Casa Azul

Image Credit: Schalkwijk/Art Resource, New York. Artwork copyright © Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Collection Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno,Mexico City. When Kahlo returned from France to Mexico after many months abroad, she found Rivera was romantically involved with another woman, and she left their home in Mexico City’s San Ángel neighborhood for Casa Azul. By late 1939 they agreed to divorce, prompting one of her largest canvases—The Two Fridas, a double self-portrait with a European Frida and a Mexican Frida whose exposed hearts are connected by an artery as they hold hands. When Kahlo’s health suffered after the divorce, Rivera reached out to Kahlo’s physician, Eloesser, for advice, and he suggested they reconcile as companions. The pair remarried in San Francisco in December 1940.

Kahlo remained mostly in Mexico City after that. Her work was shown in group exhibitions in Mexico and the United States in the 1940s, including “Twentieth Century Portraits” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1942 and “Exhibition by 31 Women”at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in 1943. In 1943 she took a teaching position at Mexico City’s School of Painting and Sculpture (commonly known as “La Esmeralda”), moving classes to the Casa Azul when her health declined.

The second of Kahlo’s solo exhibitions during her lifetime took place in the summer of 1953 in Mexico City at Lola Álvarez Bravo’s Gallery of Contemporary Art. Already in poor health by then, Kahlo was delivered to the opening night festivities on a stretcher and then placed in her four-poster bed, which had been brought to the gallery. “The show became more a court affair than a normal opening,” wrote critic Anita Brenner in her review of the show for the summer 1953 issue of ARTnews. “As a result, critics tended to react in a hostile way, as if they resented the atmosphere of incense and awe. Actually Frida, who has been extremely ill, is extraordinarily courageous about continuing her work under conditions that might have destroyed anybody with less admirable toughness.” The same year, Kahlo’s right leg was amputated below the knee.

Kahlo died at the Casa Azul at age 47 on July 13, 1954, due either to pulmonary embolism or possibly to suicide. Her casket was installed in the rotunda of the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, where prominent mourners such as former president Lázaro Cárdenas paid their respects.

Her last painting was a still life of watermelons on which she inscribed the words Viva la Vida (“long live life”), now on permanent display at the Casa Azul, which became a museum just four years after her death. Now a sort of pilgrimage site for those clamoring to see the house where Kahlo was born, raised, and died, it includes the artist’s personal collection of folk art, photos, her famous four-poster bed, her pigments and brushes next to the easel gifted to her by Nelson Rockefeller—and even the urn holding her ashes.

“I am not sick. I am broken,” Kahlo once wrote in her diary. “But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.”

-

Image Credit: Copyright © DeA Picture Library/Art Resource, New York.

Early beginnings

Born on July 6, 1907, Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón grew up in the Mexico City suburb of Coyoacán in a blue house built by her father and nicknamed the Casa Azul. (She’d later amend her birth year from 1907 to 1910 so that it coincided with the beginning of the Mexican Revolution that she held so dear.) Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was a German-Jewish photographer, and her mother, Matilde Calderón, was a Catholic of indigenous and Spanish heritage. Kahlo was the third of four sisters and close with her father, who trained her to help him in the photography studio from a young age.

When she was six years old, Kahlo contracted polio, which rendered her right leg and foot permanently smaller than her left. More than just a fashion statement emphasizing her Mexican identity, the floor-length skirts that would become part of Kahlo’s uniform were a way to deflect attention from this deformity.

In 1922 Kahlo started studying at Mexico City’s Escuela Nacional Preparatoria with a focus on sciences and became part of a group of communist activist students called Las Cachuchas (“The Caps”). During her years there, los tres grandes (the big three artists of Mexican Muralism—David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco) all worked on early murals at her school. Kahlo met Rivera briefly when he was painting in the school amphitheater; they wouldn’t meet again until 1928.

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo and her boyfriend were riding a bus that collided with a trolley car. Some passengers were killed; Kahlo sustained fractures of her spine, right leg, collarbone, pelvis, and right foot and serious internal injuries. Hospitalized for a month after the accident, Kahlo was fitted with a plaster corset, versions of which she would have to wear for the rest of her life. Due to her injuries from this accident, she later had multiple miscarriages and therapeutic abortions and underwent more than 30 surgical procedures.

Kahlo started painting during her long recovery in bed. Using a portable easel and a mirror that her mother had installed on the underside of her four-poster bed, Kahlo began with the most readily available subject: herself. It was a subject she would return to again and again as she used self-portraits to illustrate her inner world during distinct moments in her eventful life.

Kahlo and Rivera

A few years after her recovery Kahlo again met Rivera through a friend, photographer Tina Modotti. Twenty years older than Kahlo, Rivera was by then an established artist. They married on August 21, 1929, forming a union that proved both turbulent and enduring. They divorced and quickly remarried. They each had affairs, sometimes with the same people. Kahlo’s liaisons famously included one with Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky (who temporarily lived in the Casa Azul during his exile in Mexico) and another with Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Kahlo and Rivera spent the early years of their marriage in the United States, with a recent book (Frida in America, 2020) positing that Kahlo experienced her “creative awakening” there and made important work while living in San Francisco, New York City, and Detroit. Kahlo arrived in San Francisco in 1930 as a 23-year-old, having never crossed the border before. “Dressed in native costume even to huaraches, she causes much excitement on the streets of San Francisco,” noted Edward Weston, who photographed the couple around that time. “People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.” He called her “a little doll alongside Diego, but a doll in size only, for she is strong and quite beautiful.”

This description could extend to Kahlo’s portrayal of herself in the marriage portrait she produced while living in San Francisco, Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931). Exaggeratedly smaller than Rivera, Kahlo and her tiny feet seem almost to float above the floor, and yet she has a look of strength that is underscored by the fiery red of her shawl.

Kahlo in America

Weston was one of many artists Kahlo befriended while in the United States. Not long after arriving in San Francisco she met photographer Dorothea Lange, who shared her studio and introduced Kahlo to someone who became a lifelong confidant, Dr. Leo Eloesser. Eloesser was one of Lange’s clients, and after meeting Kahlo he carefully diagnosed her injuries and remained one of her most trusted friends until her death.

While in America, Rivera was the one sought out for mural commissions and other projects. Kahlo was still emerging as an artist but certainly left an impression. “I think,” said Imogen Cunningham, who photographed Kahlo in San Francisco, “that she was a better painter than Diego. She never got any credit.” Indeed, a 1933 article about her published in a Detroit newspaper was headlined “Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art,” placing Kahlo firmly in the shadow of her better-known partner. Still, she was not without confidence: “Of course, he does well for a little boy,” she quipped about Rivera in the article. “But it is I who am the big artist.”

Already at this early stage of her career, Kahlo was confident in a dreamlike style that nevertheless communicated her personal experience.

Kahlo the big artist

Kahlo’s career shifted around 1938 as her work began to gain recognition. She made her first-ever sale that summer, when Hollywood actor and collector Edward G. Robinson visited Rivera’s studio. Rivera showed Robinson Kahlo’s paintings, and the actor bought four canvases for $200 each. Kahlo later wrote, “For me it was such a surprise that I marveled and said, ‘This way I am going to be able to be free. I’ll be able to travel and do what I want without asking Diego for money.’”

A few months later, Kahlo had her first solo show, one of only two mounted during her lifetime, exhibiting 25 paintings at New York’s Julien Levy Gallery. The November opening drew an A-list crowd including Alfred Stieglitz, curator Alfred H. Barr, art historian Meyer Schapiro, and Georgia O’Keeffe (whom Kahlo had befriended on her first trip to New York). André Breton, who had met Kahlo in Mexico and called her a Surrealist (a label she rejected, since she believed her work represented her lived reality), wrote a catalog essay describing Kahlo’s work as “a ribbon around a bomb.” Time magazine reviewed the show, reporting that “too shy to show her work before, black-browed little Frida has been painting since 1926, when an automobile smashup put her in a plaster cast, ‘bored as hell.’”

Kahlo exhibited Pitahayas (1938) at Julien Levy, one of the roughly 30 still-life paintings she executed during her life (as compared with around 80 self-portraits). The oil-on-aluminum work shows five rotting pitahaya fruits leaning against volcanic rocks and a cactus, one sliced open as a small sketched figure of a skeleton points a scythe in its direction. Pitahayas and 17 other paintings traveled directly from New York to Paris, where in 1939 Kahlo participated in a group show of Mexican art at the Pierre Colle Gallery. The show was arranged by Breton with help from Marcel Duchamp, whom Kahlo described as “the only one among the painters and artists here who has his feet on the ground and his brains in their place”).

Among the works in the exhibition was The Frame (1938), a portrait of herself crowned with yellow flowers that Kahlo inserted into the center of a small, reverse glass painting of blossoms that she had bought in Oaxaca. The work was acquired by the French state and now is part of the Centre Pompidou collection. (Though Kahlo’s oeuvre is relatively small, her works would eventually land in other high-profile collections as well, such as New York’s Museum of Modern Art, SFMOMA, Mexico City’s Museo de Arte Moderno and the National Museum of Women in the Arts.)

Back to the Casa Azul

When Kahlo returned from France to Mexico after many months abroad, she found Rivera was romantically involved with another woman, and she left their home in Mexico City’s San Ángel neighborhood for Casa Azul. By late 1939 they agreed to divorce, prompting one of her largest canvases—The Two Fridas, a double self-portrait with a European Frida and a Mexican Frida whose exposed hearts are connected by an artery as they hold hands. When Kahlo’s health suffered after the divorce, Rivera reached out to Kahlo’s physician, Eloesser, for advice, and he suggested they reconcile as companions. The pair remarried in San Francisco in December 1940.

Kahlo remained mostly in Mexico City after that. Her work was shown in group exhibitions in Mexico and the United States in the 1940s, including “Twentieth Century Portraits” at the Museum of Modern Art in 1942 and “Exhibition by 31 Women”at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery in 1943. In 1943 she took a teaching position at Mexico City’s School of Painting and Sculpture (commonly known as “La Esmeralda”), moving classes to the Casa Azul when her health declined.

The second of Kahlo’s solo exhibitions during her lifetime took place in the summer of 1953 in Mexico City at Lola Álvarez Bravo’s Gallery of Contemporary Art. Already in poor health by then, Kahlo was delivered to the opening night festivities on a stretcher and then placed in her four-poster bed, which had been brought to the gallery. “The show became more a court affair than a normal opening,” wrote critic Anita Brenner in her review of the show for the summer 1953 issue of ARTnews. “As a result, critics tended to react in a hostile way, as if they resented the atmosphere of incense and awe. Actually Frida, who has been extremely ill, is extraordinarily courageous about continuing her work under conditions that might have destroyed anybody with less admirable toughness.” The same year, Kahlo’s right leg was amputated below the knee.

Kahlo died at the Casa Azul at age 47 on July 13, 1954, due either to pulmonary embolism or possibly to suicide. Her casket was installed in the rotunda of the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, where prominent mourners such as former president Lázaro Cárdenas paid their respects.

Her last painting was a still life of watermelons on which she inscribed the words Viva la Vida (“long live life”), now on permanent display at the Casa Azul, which became a museum just four years after her death. Now a sort of pilgrimage site for those clamoring to see the house where Kahlo was born, raised, and died, it includes the artist’s personal collection of folk art, photos, her famous four-poster bed, her pigments and brushes next to the easel gifted to her by Nelson Rockefeller—and even the urn holding her ashes.

“I am not sick. I am broken,” Kahlo once wrote in her diary. “But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.”

RobbReport

Rolex’s Epic New London Flagship Likely Won’t Open Until 2025

WWD

Stella McCartney Enters the Supplement Category

BGR

12.9-inch iPad Air 6 design just leaked with no surprises at all

Sportico

Caitlin Clark Collision Raises Questions About Arena Security

SPY