For the first time, in 2022, the Biennale de Lyon expanded its footprint, displaying artwork across the France’s third largest city, which brought in 274,225 visitors, with nearly half being under 26. For its 2024 edition, the Biennale has taken its expansion a step further by extending outside the city to the towns of Brioude and Charlieu, alongside nine venues in Lyon. While the traditional Musée d’art contemporain de Lyon (macLyon) hosts around a third of the 78 exhibiting artists, Les Grandes Locos, a former train maintenance center, and the Cité internationale de la Gastronomie, a 12th-century hospital recently repurposed into a cultural center for food and cuisine, are new sites for the recurring exhibition’s 17th edition.

With the title “Crossing the water,” this Lyon Biennale offers artworks, many of which are new commissions, that are all about relationships. Organized by guest curator Alexia Fabre, director of the Beaux Arts de Paris school, and Biennale artistic director Isabelle Bertolotti, the exhibition explores how one approaches differences and what that can teach us. Fabre’s intention was to create a pathway along the Rhône, which she described as “a metaphor for all waterways that connect to form a stronger current,” which she connected to the 15 arrondissements of Lyon’s metropolitan area and the wider Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region, the regional government of which coproduced several projects, including Mona Cara’s breathtaking tapestry Le Cactus.

Below, a look at nine outstanding works on view at the 2024 Lyon Biennale, which runs through January 5.

-

Michel de Broin

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/Courtesy the artist At Les Grandes Locos, make sure to look up at the building’s vaulted ceiling, which is starred with neon lights as a way to highlight recent repairs. This installation by Canadian artist Michel de Broin (b. 1971) shows the tension between the venue’s architectural grid and the geological forces that have been altering it since its inauguration in 1846. “By cementing the building’s cracks and scars, stonemasons have generated an alphabet of shapes, which I approached as pictorial motifs,” de Broin told ARTnews, adding that his project aims to celebrate the beauty of imperfections. “All I had to do is cut out the fruit of their interventions with fine lines of light.” Titled Mortier Fati – Lignes de lumière (Fati Mortar – Lines of Light), the sculpture refers to mortar, that mixture of cement, lime, sand and water which binds constructions together, as well as to the Nietzschean notion of amor fati (love for fate), an encouragement to embrace our destiny rather than to fight the inevitable.

-

Iván Argote

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/©2024 ADAGP, Paris/Courtesy the artist, Noor, and Havas Upon arrival at Les Grandes Locos, it is impossible to miss The Other, Me and the Others by Colombian artist Iván Argote (b. 1983). This massive, interactive installation looks like a giant seesaw with a platform that tilts from one side to the other, depending on where visitors stand on it. Its up and down motions mirror the ups and downs of life. A bond that was once tight can loosen over time; people fall in and out of love. This pace of our connections with others is what Argote’s work, which he considers a “playground open to all, a place of encounters and even of power,” gets at.

-

Pilar Albarracín

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/©2024 ADAGP, Paris/Courtesy Galerie Georges-Philippe & Nathalie Vallois Halloween may be over a month away, but there is something spooky in this installation, where household appliances come to life. This fantastical scene, however, is no prank, but a call for revolution. Subversive feminist artist Pilar Albarracín (b. 1968), known for work that deconstructs the concept of Spanish identity, has brought 50 pressure cookers to Les Grandes Locos, which at one point in its history was the site of workers fighting for their rights. These kitchen appliances let off steam in tune with the Socialist International anthem. Titled Marmites enragées (Raging Cookers), the installation ridicules the regressive idea that women should stay in the kitchen.

-

Oliver Beer

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/Courtesy the artist, Thaddaeus Ropac, and Almine Rech Oliver Beer’s installation is, without a doubt, the climax of the Biennale’s display at Les Grandes Locos’s display. The artist had initially conceived of this work when he first participated in the Lyon Biennale a dozen years ago. When he was finally granted access to La Grotte de Font-de-Gaume, Palaeolithic caves located in the Dordogne department in southwest France, Beer invited eight performers—Jean-Christophe Brizard, eee gee, Mélissa Laveaux, Mo’Ju, Hamed Sinno, Michiko Takahashi, Rufus Wainwright, and Woodkid—to each sing their earliest musical memory and a melody of Beer’s choice, so that he could merge their voices into the ultimate polyphony.

This acoustic journey has been adapted into an immersive, two-floor installation, called Resonance Project (The Cave), 2024, consisting of eight screens that switch on and off intermittently. Each performer appears singing a cappella and holding a lamp, as if they were archaeologists exploring the site’s murals and crevasses. Resonance Project’s underground gallery hosts paintings that translate this musical experience pictorially. Beer poured pigments collected in the caves onto canvases that he had laid flat atop speakers playing the sounds recorded on site, the vibrations serving as the paintbrush. The video runs 30 minutes, but I found myself having trouble leaving after just one screening.

-

Lyz Parayzo

Image Credit: Photo Perrine Géliot/Courtesy the artist Illuminated by a soft pink light, it’s hard to tell if the hanging sculptures here are giant silver earrings or rotating saws that could cut you in half. The answer might be a bit of both. These jagged spirals may shield you if you stand cautiously in the middle of the room, or hurt you if you were to come too close. “These are shapes I primarily drew on paper,” said Brazilian artist and trans rights activist Lyz Parayzo (b. 1994), who grew up watching her grandfather make jewelry. “My first performances in the art world were very disruptive. I am slowly shifting toward sculpture, because I don’t think I need to be as aggressive to make a point.” Parayzo’s double-edged installation, titled Cuir Mouvement (Leather Movement), acts as armor and weapon. It’s both seductive and repelling. “I am obsessed with saws and almost wanted them to dance. And I love pink, which is a very feminine color, but I also love that people do not necessarily like pink,” she added.

-

Lorraine de Sagazan and Anouk Maugein

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lane/Courtesy the artists At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, when theaters were closed to rehearsals and shows, actor and director Lorraine de Sagazan (b. 1986) developed a body of work that is based on conversations with strangers about death and justice. With scenographer Anouk Maugein, she turned those interviews into Monte di Pietà (Pawnshop) an ever-growing mixed-media installation that was first presented at the Villa Médicis in Rome, then at the Collection Lambert in Avignon. The objects on view at the macLyon—a metronome, a giant teddy bear, a tire, a hat, and much more—were donated by people who were wronged in their lives and whom the legal system has failed. Theirstories have been translated into words by poet Laura Vazquez, like this woman’s recounting: “This is my rapist’s book / my case was dismissed / I am not done reading it / I don’t want to see it anymore / take it away.” The installation is activated when actors perform Vasquez’s lines in the exhibition space. “By creating a distancing effect, literature can become a refuge,” said de Sagazan.

-

Florian Mermin

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/©2024 Adagp, Paris/Courtesy the artist The Cité internationale de la Gastronomie – Hôtel Dieu is set in a 12th-century hospital. When Florian Mermin (b. 1991) stepped into what used to be the hospital’s apothecary shop, he immediately knew this was where he wanted his work to be showcased. The remaining display of earthenware pots, formerly filled with oils and ointments, inspired the French artist to appeal not only to sight but also smell. “Perfume has to do with memories and seduction. It can also be disturbing, depending on your perception, condition, or life experience,” he said. “When I entered this room, I instantly knew I wanted to sculpt a flower.” Breathe in, and you will certainly recognize the scent. After meeting horticulturists and studying a royal herbarium featuring 3 million species, Mermin chose to depict a violet, a flower with soothing properties. His wax sculpture is inlaid with fragments of amethyst and violet-flavor candies. When light is reflected in those elements, the work almost looks like a giant jewel.

-

Ines Katamso

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/Courtesy the artist and ISA Art Gallery, Jakarta. Co-production Ellipse Art Projects et Jeune création internationales — Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes Indonesia is drowning in garbage. Since a 2019 meeting in Geneva where 187 countries approved the first ever global rules on cross-border shipments of plastic waste, the country has been trying to reduce the deluge of trash and scraps from wealthier nations that has made its way to Indonesia’s shores for decades. This story is taken up in the installation Welcome to the Plastic Age by Ines Katamso (b. 1990), winner of the inaugural +E mentorship program for emerging artists which comes with a residency in France to create a work for the Biennale. Her installation, which fills an entire gallery at Villeurbanne’s Institut d’art contemporain (IAC), suggests that we have tolerated plastic so much, that it has become a part of us. Katamso has re-created an arid, sterile, dystopian landscape populated with plants and chimeras made from plastic, which she sees as a “faceless monster.” If no action is taken soon, this is what our future looks like Katamso says.

-

Hilary Galbreaith

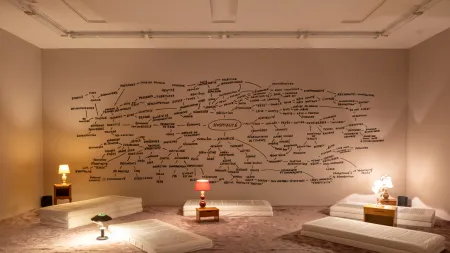

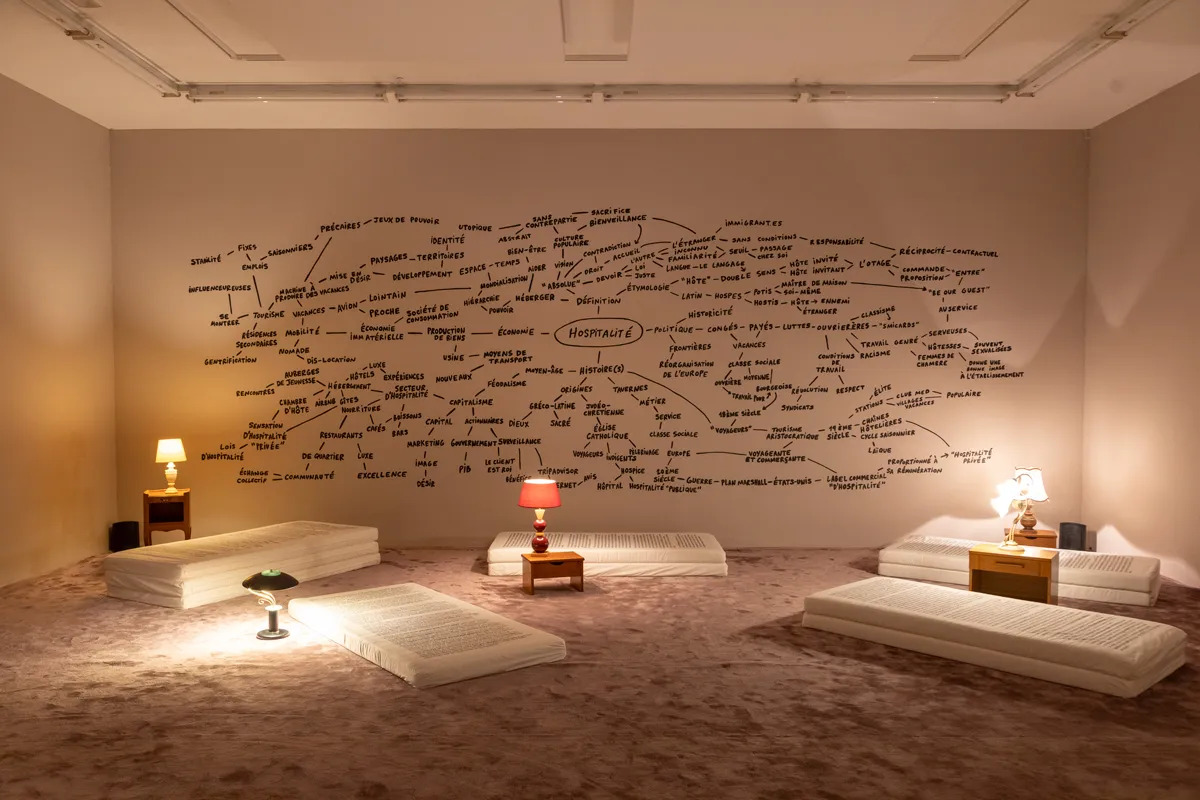

Image Credit: Photo Jair Lanes/©2024 ADAGP, Paris/Courtesy the artist The IAC also presents Be Our Guest by American artist Hilary Galbreaith (b. 1989). This mixed-media installation stems from a reflection on hospitality, an Anglophone notion that is spreading in France. “I started examining the contradiction between the meaning of hospitality, that is welcoming someone else without expecting any profit, and the point of the hospitality industry, which is to make money,” said Galbreaith, who is now based in Rennes and has worked in French restaurants, bars, and cafés. “In France, I have had great experiences. I really liked the savoir-faire but could not help noticing the violence in the workplace around sexism, racism, and classism.”

For the piece, Galbreaith interviewed 29 people from the French hospitality industry—waiters, bartenders, receptionists—and transcribed 16 of these accounts in the sans serif font that TripAdvisor uses onto mattresses. All around are second-hand lamps and tables that give off an intimate yet hipster vibe. The background soundtrack recalls elevator or lounge music. On the wall, Galbreaith has drawn the mind map of all her research. “I chose to do it in this form because, besides French philosopher Jacques Derrida, there are not very reliable sources about this [spread of hospitality to France],” she said. “I could only find texts in English that had been funded by hotels, which wanted to connect themselves to this narrative.”

Michel de Broin

At Les Grandes Locos, make sure to look up at the building’s vaulted ceiling, which is starred with neon lights as a way to highlight recent repairs. This installation by Canadian artist Michel de Broin (b. 1971) shows the tension between the venue’s architectural grid and the geological forces that have been altering it since its inauguration in 1846. “By cementing the building’s cracks and scars, stonemasons have generated an alphabet of shapes, which I approached as pictorial motifs,” de Broin told ARTnews, adding that his project aims to celebrate the beauty of imperfections. “All I had to do is cut out the fruit of their interventions with fine lines of light.” Titled Mortier Fati – Lignes de lumière (Fati Mortar – Lines of Light), the sculpture refers to mortar, that mixture of cement, lime, sand and water which binds constructions together, as well as to the Nietzschean notion of amor fati (love for fate), an encouragement to embrace our destiny rather than to fight the inevitable.

Iván Argote

Upon arrival at Les Grandes Locos, it is impossible to miss The Other, Me and the Others by Colombian artist Iván Argote (b. 1983). This massive, interactive installation looks like a giant seesaw with a platform that tilts from one side to the other, depending on where visitors stand on it. Its up and down motions mirror the ups and downs of life. A bond that was once tight can loosen over time; people fall in and out of love. This pace of our connections with others is what Argote’s work, which he considers a “playground open to all, a place of encounters and even of power,” gets at.

Pilar Albarracín

Halloween may be over a month away, but there is something spooky in this installation, where household appliances come to life. This fantastical scene, however, is no prank, but a call for revolution. Subversive feminist artist Pilar Albarracín (b. 1968), known for work that deconstructs the concept of Spanish identity, has brought 50 pressure cookers to Les Grandes Locos, which at one point in its history was the site of workers fighting for their rights. These kitchen appliances let off steam in tune with the Socialist International anthem. Titled Marmites enragées (Raging Cookers), the installation ridicules the regressive idea that women should stay in the kitchen.

Oliver Beer

Oliver Beer’s installation is, without a doubt, the climax of the Biennale’s display at Les Grandes Locos’s display. The artist had initially conceived of this work when he first participated in the Lyon Biennale a dozen years ago. When he was finally granted access to La Grotte de Font-de-Gaume, Palaeolithic caves located in the Dordogne department in southwest France, Beer invited eight performers—Jean-Christophe Brizard, eee gee, Mélissa Laveaux, Mo’Ju, Hamed Sinno, Michiko Takahashi, Rufus Wainwright, and Woodkid—to each sing their earliest musical memory and a melody of Beer’s choice, so that he could merge their voices into the ultimate polyphony.

This acoustic journey has been adapted into an immersive, two-floor installation, called Resonance Project (The Cave), 2024, consisting of eight screens that switch on and off intermittently. Each performer appears singing a cappella and holding a lamp, as if they were archaeologists exploring the site’s murals and crevasses. Resonance Project’s underground gallery hosts paintings that translate this musical experience pictorially. Beer poured pigments collected in the caves onto canvases that he had laid flat atop speakers playing the sounds recorded on site, the vibrations serving as the paintbrush. The video runs 30 minutes, but I found myself having trouble leaving after just one screening.

Lyz Parayzo

Illuminated by a soft pink light, it’s hard to tell if the hanging sculptures here are giant silver earrings or rotating saws that could cut you in half. The answer might be a bit of both. These jagged spirals may shield you if you stand cautiously in the middle of the room, or hurt you if you were to come too close. “These are shapes I primarily drew on paper,” said Brazilian artist and trans rights activist Lyz Parayzo (b. 1994), who grew up watching her grandfather make jewelry. “My first performances in the art world were very disruptive. I am slowly shifting toward sculpture, because I don’t think I need to be as aggressive to make a point.” Parayzo’s double-edged installation, titled Cuir Mouvement (Leather Movement), acts as armor and weapon. It’s both seductive and repelling. “I am obsessed with saws and almost wanted them to dance. And I love pink, which is a very feminine color, but I also love that people do not necessarily like pink,” she added.

Lorraine de Sagazan and Anouk Maugein

At the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, when theaters were closed to rehearsals and shows, actor and director Lorraine de Sagazan (b. 1986) developed a body of work that is based on conversations with strangers about death and justice. With scenographer Anouk Maugein, she turned those interviews into Monte di Pietà (Pawnshop) an ever-growing mixed-media installation that was first presented at the Villa Médicis in Rome, then at the Collection Lambert in Avignon. The objects on view at the macLyon—a metronome, a giant teddy bear, a tire, a hat, and much more—were donated by people who were wronged in their lives and whom the legal system has failed. Theirstories have been translated into words by poet Laura Vazquez, like this woman’s recounting: “This is my rapist’s book / my case was dismissed / I am not done reading it / I don’t want to see it anymore / take it away.” The installation is activated when actors perform Vasquez’s lines in the exhibition space. “By creating a distancing effect, literature can become a refuge,” said de Sagazan.

Florian Mermin

The Cité internationale de la Gastronomie – Hôtel Dieu is set in a 12th-century hospital. When Florian Mermin (b. 1991) stepped into what used to be the hospital’s apothecary shop, he immediately knew this was where he wanted his work to be showcased. The remaining display of earthenware pots, formerly filled with oils and ointments, inspired the French artist to appeal not only to sight but also smell. “Perfume has to do with memories and seduction. It can also be disturbing, depending on your perception, condition, or life experience,” he said. “When I entered this room, I instantly knew I wanted to sculpt a flower.” Breathe in, and you will certainly recognize the scent. After meeting horticulturists and studying a royal herbarium featuring 3 million species, Mermin chose to depict a violet, a flower with soothing properties. His wax sculpture is inlaid with fragments of amethyst and violet-flavor candies. When light is reflected in those elements, the work almost looks like a giant jewel.

Ines Katamso

Indonesia is drowning in garbage. Since a 2019 meeting in Geneva where 187 countries approved the first ever global rules on cross-border shipments of plastic waste, the country has been trying to reduce the deluge of trash and scraps from wealthier nations that has made its way to Indonesia’s shores for decades. This story is taken up in the installation Welcome to the Plastic Age by Ines Katamso (b. 1990), winner of the inaugural +E mentorship program for emerging artists which comes with a residency in France to create a work for the Biennale. Her installation, which fills an entire gallery at Villeurbanne’s Institut d’art contemporain (IAC), suggests that we have tolerated plastic so much, that it has become a part of us. Katamso has re-created an arid, sterile, dystopian landscape populated with plants and chimeras made from plastic, which she sees as a “faceless monster.” If no action is taken soon, this is what our future looks like Katamso says.

Hilary Galbreaith

The IAC also presents Be Our Guest by American artist Hilary Galbreaith (b. 1989). This mixed-media installation stems from a reflection on hospitality, an Anglophone notion that is spreading in France. “I started examining the contradiction between the meaning of hospitality, that is welcoming someone else without expecting any profit, and the point of the hospitality industry, which is to make money,” said Galbreaith, who is now based in Rennes and has worked in French restaurants, bars, and cafés. “In France, I have had great experiences. I really liked the savoir-faire but could not help noticing the violence in the workplace around sexism, racism, and classism.”

For the piece, Galbreaith interviewed 29 people from the French hospitality industry—waiters, bartenders, receptionists—and transcribed 16 of these accounts in the sans serif font that TripAdvisor uses onto mattresses. All around are second-hand lamps and tables that give off an intimate yet hipster vibe. The background soundtrack recalls elevator or lounge music. On the wall, Galbreaith has drawn the mind map of all her research. “I chose to do it in this form because, besides French philosopher Jacques Derrida, there are not very reliable sources about this [spread of hospitality to France],” she said. “I could only find texts in English that had been funded by hotels, which wanted to connect themselves to this narrative.”

Ralph Lauren’s New Vintage Program Makes the Brand’s Rare Threads Easier to Find

Alix Earle Gives the Oversize Jacket Trend a Fiery Twist at the Isabel Marant Show During Paris Fashion Week

Here’s why you should get ready to pay a lot more for ChatGPT Plus

Randy Orton Tattoos in WWE 2K Raise Copyright Concerns